I’ve moved to substack!

This blog is now available at https://porterszucs.substack.com.

Professor of History, University of Michigan

This blog is now available at https://porterszucs.substack.com.

Cultural and social history are a bit like geology. Things change, but so slowly that it isn’t always obvious what happened until long afterwards. While political history operates on a much faster timeline, even here we often see events that churn the soil even while the bedrock moves at a glacial pace. Just consider the shift that happened between the elections of 2007 and 2015. The former is widely viewed as a humiliating repudiation of Jarosław Kaczyński’s Law and Justice Party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, or PiS), while the latter marked their triumphant comeback with a self-proclaimed mandate to transform Poland. Analysts rushed to develop theories of why “the Poles” repudiated liberal democracy. Lost in the flurry of punditry was the fact that in 2007 PiS won 5,183,477 votes, and in 2015 they got 5,711,687 – out of a population of eligible voters of over thirty million people. Put differently, just under 2% of the electorate moved into PiS’s column. The consequences were enormous, but if we step back a few steps we realize that Polish society changed hardly at all.

With this in mind, what’s been happening in Poland over the past year has been stunning. It is as if a dam has broken, and the resulting wave has made Polish politics almost unrecognizable.

Starting from a bird’s eye view, support for PiS has fallen off a cliff. During the elections of October, 2019, PiS got 43.59% of the votes—not a majority, but in the fragmented political landscape of Poland, a relatively strong showing. Although the pre-election surveys had varied quite a bit (mostly because of different methodologies), the average of all the polls during the month before that election had predicted roughly this result. At the start of the COVID pandemic in March, 2020, PiS had lost some support, but a “rally around the flag during a crisis” sentiment pulled them back up to 44%. It’s been all downhill from there. The average of all polls currently has PiS at 31.6%, with a range from 26% (using live telephone interviews) to one extreme outlier at 40% (using an automated internet survey). Jarosław Kaczyński is currently the most unpopular politician in the country, with a favorability rating of 17% and an unfavorability rating at a jaw-dropping 74%. Other right-wing politicians aren’t far behind: President Andrzej Duda’s is disliked by 64% of Poles, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki by 62%, and Justice Minister Zbigniew Ziobro (ironically, Kaczyński’s leading rival for leadership of the far right) by 71%.

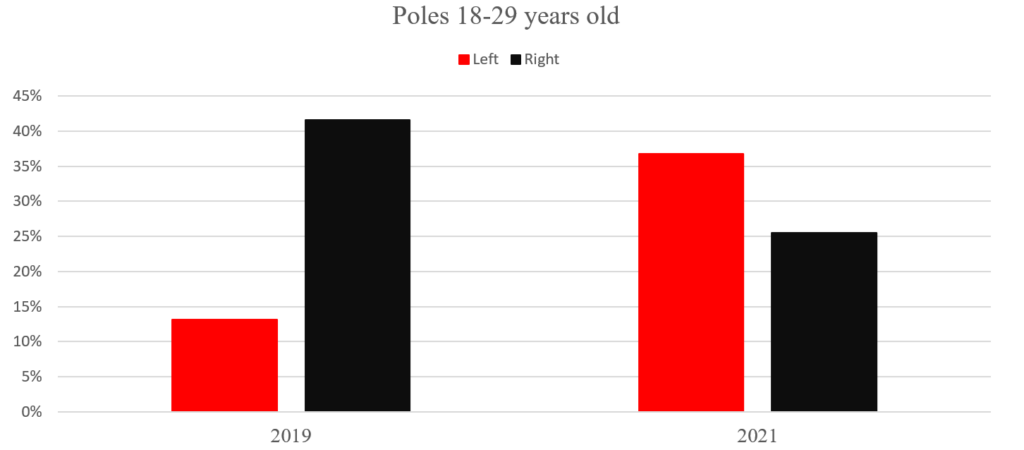

As dramatic as those numbers are, there is an even greater tectonic shift just underneath them. Put simply, young people have abandoned PiS almost entirely. In 2019 the supporters of PiS already skewed somewhat towards more elderly voters, with 55% of their voters age 50 or above. Today, 76% of the party’s support comes from us oldsters. Among those under age 30, the current government has the trust of a whopping 9%. 34% of that cohort consider themselves to be somewhat leftist or very leftist, compared to 28% who affiliate with the right. That last figure needs to be put into perspective to see what has happened. A different survey compared 18-29 year-olds in Poland between 2019 and 2021, and found that their affiliation flipped from right to left over the course of those two years.

Not surprisingly, nearly all of this change has come among women. Whereas in 2019 a plurality of both women and men under 30 identified with the right, by 2021 a plurality of women supported the left, while a (slightly smaller) plurality of men supported the right. Among young men, right-wing views remain twice as popular as left-wing views, but women have swung in a completely different direction.

I’m sure that the PiS government’s bad management of the COVID crisis has contributed to the overall fall in support, but that’s not the biggest issue here. The erosion of constitutional rule and the separation of powers has continued apace since PiS’s re-election in 2019, but the sort of people upset by those matters were already aligned with the opposition. The big change came when the subordination of the judiciary was brought home to everyone—above all, Polish women—in the most intimate way possible, when the constitutional tribunal banned nearly all abortions last fall. The mass protest movement that exploded in response—which took the name of the “Women’s Strike”—has dwarfed every previous expression of opposition to Law and Justice rule. The government has responded with (still relatively contained) demonstrations of force, but this has only made the Women’s Strike stronger.

I’ve heard some grumbling among those who have opposed PiS from the start—people of my generation who are nowadays labeled dziadersi (a slang similar to “boomer” in English, but with an angrier edge to it). “Where were all these protesters in 2016 and 2017,” my friends say, “when we warned that undermining the rule of law and the constitutional protections of our civil rights would lead us to precisely this sort of catastrophe?” It’s true that the stage for the abortion ban was set when PiS subordinated the judiciary to political control, but let’s be more understanding. It required a relatively high level of political engagement to be directly touched by what Kaczyński was doing during those early years; meanwhile, nearly everyone at the time noticed the 500 złoty monthly payments that PiS introduced for struggling families. And the anti-PiS opposition was led by…well, dziadersi, and far too many of us were still fighting the political battles of the 1990s and early 2000s. The abortion ban is, in a way, a civics lesson for all of us. For some, it shows that when judicial independence is eliminated, the results will sooner or later hit everyone. For others, it serves as a reminder that polite 20th century liberalism doesn’t have much to offer in the precarious world of 2021.

It’s a very open question what will happen now, but one thing is beyond doubt: Polish political culture has been utterly transformed. It is time for the generation of 2020 to set the agenda, and the world they eventually create will not have much space for the ideas and ideals that PiS tried to impose upon Poland. Kaczyński might hold on to power for a few more years. It’s even possible that he will resort to even more authoritarian measures, so that things will get worse before they get better. But his primary goal has always been more than just holding power: he wanted to shape the worldview of the next generation of Poles.

Ironically, he did. Just not in the way he wanted.

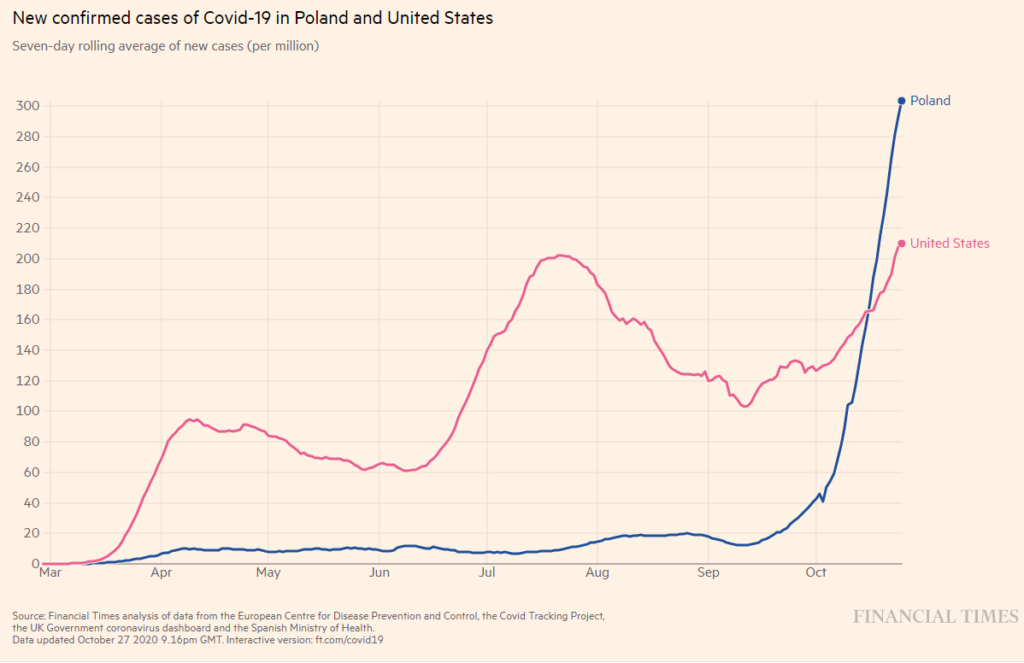

Something very strange is happening to the coronavirus in Poland right now. If we look at the number of new confirmed cases, we see a success story.

In mid November it seemed that the country was only days from a return to a full lockdown, which the government had announced would automatically happen if the country had more than 700 cases per million. Then, after reaching 674, the numbers began plummeting. It would seem that preventative measures (an expanded mask mandate; closing shopping malls; switching to remote learning for schools and universities; limiting ridership on public transportation; closing theaters, cinemas, museums, restaurants, and nightclubs; limiting shopping to essentials only) had worked. The dreaded “national quarantine” specified in the emergency COVID legislation was avoided.

But something wasn’t right with this picture. Hospitals were reporting that they continued to be overwhelmed, and the death rate continued to rise, then to decline only slightly this past week.

To some extent this was to be expected: fatalities lag behind reports of new cases because COVID kills with agonizing slowness. But it does seem odd that the disparity between these two charts is as large as it is, and that the health care workers on the front lines don’t seem to be witnessing significant improvements.

It is also counterintuitive that cases would be declining in the midst of the massive public protests of the Women’s Strike. Although the participants in that action are adhering to mask regulations, the lack of social distancing inevitably created a public health challenge. On November 11, for example, hundreds of thousands took to the streets.

These crowds are entirely understandable. Given the public health implications of the near total ban on abortion that sparked these protests, it makes sense to balance the risks. Nonetheless, those risks are real, and it would be surprising if these huge gatherings were followed by a decline in the number of cases.

It turns out that this discrepancy is quite easy to explain, and others following the data were quick to figure it out. To see what’s up, we need one more chart:

Donald Trump was appropriately ridiculed when he suggested that case numbers of COVID could be reduced by simply testing less. Well, it seems that the Polish government took that advice to heart. They ran fewer tests, found fewer cases, and avoided the national quarantine—problem solved!

Unfortunately, it isn’t quite as simple as that. Yes, the PiS government scaled back its testing programs, but this has been accompanied by a growing reluctance among Poles to get tested. Journalists are confirming what I have heard anecdotally from friends: that people are afraid of being tested because a positive result would require them to go into quarantine. In other words, they are considering only the personal implications of a test, not the public-health considerations. An admittedly unscientific internet survey of 6,500 Poles asked whether they would get tested if they had COVID symptoms. The responses:

– 31%: Definitely yes

– 24%: Only if I felt really bad

– 22%: I don’t know—it would depend on many factors

– 23%: Definitely not

We Americans certainly have nothing to be proud of when it comes to our response to the pandemic, even if we set aside the unconscionable neglect of the problem by the Trump administration. It isn’t any consolation that people in other countries are doing just as badly, thought it does put our failings into a broader context. Poles do not have levels of absolute COVID denial comparable to the US. 74% of Poles surveyed in October consider the danger to be “serious” or “very serious,” compared to only 41% in the United States. 10% of Poles refused to believe in the existence of the pandemic, and another 8% said that it was real, but not dangerous. In another survey, 55% of Poles reported that they fear personally catching the disease, while 33% said that they did not. Somewhat incongruously, at least one survey showed the American figure to be precisely the same. One possible explanation for this (assuming it isn’t just an artifact of how the questions in different surveys were worded) is that fear of the personal consequences of COVID are comparable in our countries, but because the issue has become so politicized, it has become nearly impossible for Republicans to take the pandemic seriously as a social problem, while equally impossible for Democrats to dismiss the gravity of the situation.

Everything from wearing a mask to supporting public health measures has become a partisan issue here. In Poland, on the other hand, the fact that COVID is a public danger is not disputed by any of the major political parties. While complaints from businesspeople have been heard in Poland, these are directed against the PiS government. In the absence of coordinated support from a major political party, their protests have been tiny. Insofar as opposition politicians have tried to ally themselves with those hurt financially by the pandemic, this has taken the form of calls for more financial aid, and not a denial of the problem itself or a false dichotomy of public health vs. the economy. Political debates about the pandemic response have focused on whether the government’s response has been adequate—not over whether there should be a response.

At first glance this might seem like a good thing for the Poles. Without the intense politicization, we don’t see a corollary to the American pattern in which half the country tries to trivialize the pandemic as a matter of principle. But there’s a flip side to this: neither do we see the enthusiastic commitment to public health from any political orientation. I wonder how many Democrats in the US would be as diligent in wearing masks and supporting lockdown restrictions if it hadn’t become a way to demonstrate their ideological affinities? In Poland, where the political considerations don’t follow the same pattern, we can find careless mask use across the political spectrum. More important, we can see more space for anyone (on the right or the left) to treat COVID as a personal issue, not a social one. If we take that stance, it makes sense to resist testing. After all, a positive result won’t lead to any particular course of treatment, because only in the most severe cases do the new treatments even apply. Someone with moderate symptoms (or no symptoms at all) has no personal reason to be tested—one does so because of a sense of social responsibility. Or rather, that’s how it works in Poland. In the US, whether we do so has become an issue of identity, not altruism. Perhaps there are more Democrats in the US than there are altruists in Poland.

This issue is about to become even more urgent as the vaccines roll out. While those who get a vaccine will enjoy personal immunity, they will balance that against (likely unfounded) fears about the vaccine’s safety. The main reason it is so urgent to set those fears aside and get the vaccine is that only widespread immunization will achieve that much-abused concept, “herd immunity.” Fortunately, in an October survey carried out across 19 countries (constituting a majority of the world’s population), over 70% of respondents said that they would get a vaccine once one was available.

However, a survey released today in Poland shows that a mere third of the population is likely to get vaccinated, compared to nearly half who will not (the remainder are undecided). The most recent polls in the US show that half the population will get vaccinated (almost two thirds of the Democrats, but minorities of Republicans and independents).

If these figures turn out to be correct, then the US will struggle with COVID longer than it needs to, while Poles will continue to grapple with the disease for the foreseeable future. No amount of statistical gamesmanship will change that reality.

The picture above says more than anything I could write here. That’s Barbara Nowacka, an opposition member of the Polish sejm, displaying her parliamentary ID to a policeman during a Women’s Strike protest yesterday. And that’s pepper spray in that bottle. A police spokesperson later said that the officer used force because he perceived Nowacka as a threat.

Nowacka is by no means the first victim of the police over the past few weeks, but the combination of her prominence in public life and the damning evidence of these photographs could make this brutal assault a tipping point.

The issue that brought protesters to the streets was abortion rights, and that should remain at the center of our attention. If last month’s constitutional tribunal ruling stands, nearly all abortions in Poland will be illegal. Beyond that vital matter, however, the stakes have become even higher in recent days as the government has ratcheted up the violence in an effort to bring the protests to an end. More and more people are turning out to protest, regardless of their opinions about abortion, and Jarosław Kaczyński is now facing a genuine popular uprising. A survey from last week revealed that 70% of Poles support the demonstrators, and PiS’s support has fallen from 44% last March to 30% now. Based on the most recent polling, if elections were held today the current government would fall to a mere 196 seats, with 231 needed for a majority.

Even that 33% level assumes that the three parties constituting the government coalition would hold together, which is far from certain. Zbigniew Ziobro’s Solidarna Polska party has been intensifying its rhetoric in an attempt to establish itself as the home for those with uncompromising radical-right views. Minister of Justice Ziobro has publicly attacked Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki for being too soft in dealings with the EU, pressure that might be behind the government’s recent veto of the EU budget. The package had included measures that would make funding contingent on adhering to European rule-of-law standards, but the authoritarian regimes in Poland and Hungary have refused to accept this. That has provoked a major European crisis, but no less important are the consequences inside Poland. Given the sustained high levels of support in Poland for EU membership (around 80%), Morawiecki’s hardline stance is one of (many) reasons for PiS’s collapse in the polls. But if the Prime Minister reaches a compromise with Brussels that goes any further than a complete repeal of the rule-of-law provision, Ziobro is certain to increase his attacks from the right. He has even threatened to pull out of the governing coalition, thus prompting new elections. This might appear like political suicide, but the relatively young Ziobro is playing the long game. He is reported to have asked Kaczyński to allow a merger of their two parties, with Ziobro designated as Kaczyński’s successor. When this proposal was rebuffed, he apparently decided that his only option was to let the current government fall so that he could rise from the ashes as the new leader of the far right. As crazy as this sounds, he would indeed be well positioned for such a position, because Kaczyński has long ensured that no one within PiS would gain enough power or popularity to ever challenge his leadership. As a result, he has no obvious successor.

I will go out on a limb and speculate that we are currently watching the end-game in the PiS saga—but it could be a long end-game. Kaczyński’s ambition has always been to gain recognition as a great Polish leader, in a pantheon with Józef Piłsudski and (more appropriately) Roman Dmowski. He did succeed in dethroning the other recent contender for that status, Lech Wałęsa, but he did not manage to put himself atop the pedestal. To do that he needed more than narrow electoral victories: he needed to win majorities akin to Victor Orbán’s in Hungary, and use that power to marginalize his opponents and establish a consensus around his version of Catholic nationalism. This has not happened—not even close. Yes, his party still has lots of support, but far less than before. And Kaczyński himself has once again returned to a status he long held: the most distrusted public figure in Poland. Whereas in November of 2019 he was at a +9 approval rating (the difference between his 46% support and 37% opposition), today he has plummeted to a negative 35 (27% vis-à-vis 62%), lower than any other politician in Poland.

The violence so powerfully exemplified by yesterday’s attack on Nowacka is an outrage for which Kaczyński himself must be held to account. Having remained without any official government function (and thus no legal responsibility) since his party took power in 2015, he finally joined the government last month as Vice-Premier responsible for security affairs. This means that he has authority over the police, which means in turn that he is legally, as well as politically and morally, responsible for what has been happening. Whether he will actually suffer the appropriate consequences for what he had done, it seems clear now that his place in history is established. It isn’t the one he wanted, but it is the one he deserves.

I can’t begin to guess precisely how the coming months will play out, though I am growing increasingly confident that PiS’s chances of holding power one year from now are diminishing. That might sound like an optimistic prediction, but it’s entirely possible that the violence could get a lot worse before we truly reach the end of this nightmare. Whether it does or not depends on what Jarosław Kaczyński decides to do next.

I was fortunate enough to be in Poland in October of 2016, when the radical-right Law and Justice Party (PiS) first attempted to roll back the already restrictive abortion laws in that country. I say “fortunate,” because I had a front-row seat to the largest display of public resistance against PiS authoritarianism. On the day planned for the protest against the legislation, the weather was as bad as it could be: cold, rainy, and gloomy. Nonetheless, hundreds of thousands of men and women came out in every city and town in Poland, creating stunning images of uninterrupted masses of umbrellas as far as the eye could see. The demonstrations were so vigorous that PiS backed down—the one and only time they have done so since taking power in 2015. PiS leader Jarosław Kaczyński seemed to realize that he could get away with eviscerating the constitution, politicizing the judiciary, turning the state media into a shameless propaganda outlet, and stoking the fires of xenophobia and homophobia—but he could not win in a direct assault against women’s rights.

Then came the stunning decision by the PiS controlled Constitutional Tribunal last Thursday, declaring that nearly all abortions in Poland would henceforth be illegal. Up until that moment, a so-called “compromise” on abortion dating from 1993 had been maintained by all the major political parties, though the pro-choice movement hardly saw it as a compromise. Abortion had been allowed if the life or health of the mother was at stake, if the pregnancy was the result of rape or incest, or if prenatal testing revealed a “severe and irreversible handicap or an untreatable life-threatening disease.” The decision last week removed that third provision, which was the clause that permitted 97% of last year’s legal abortions in Poland.

The reaction to the court ruling was immediate and overwhelming, dwarfing even the “black Monday” protests of 2016. Each day since Thursday, the resistance has grown stronger. On Sunday there were protests at (and sometimes inside) churches all over the country, reflecting the fact that the Catholic Church has been strongly urging PiS to close the remaining possibilities for abortion in Poland. Ironically, the Conference of Bishops responded like the dog that actually caught the truck: their spokesperson stated that they had not wanted to push the issue at this time, and that they continued to support the old “compromise” legislation. Today there were road blockades that brought traffic to a halt in every Polish city and many smaller towns, and tomorrow the protestors are calling for a general strike, and urging businesses to close so that their employees can participate without repercussions. It will be interesting to see which firms are willing to be identified with PiS, because any business that stays open tomorrow will risk gaining that reputation.

One of the strongest weapons in the PiS arsenal since 2015 has been their ability to simply wait out protests. Time after time, they have done very little as the opposition attempted to rally against each successive outrage, each constitutional violation, each move towards authoritarianism. This tactic revealed a painful truth: PiS has all the power in Poland, and they don’t need to react to popular outrage. They have a firm base of electoral support that never goes much below or above 38-40 percent, and that’s been enough (so far) to maintain power in the face of a disunited opposition. Back in 2015 and 2016 there were protests that drew hundreds of thousands of people, then in the ensuing years there were tens of thousands, then thousands, then hundreds. Increasingly people came to realize that protesting didn’t change anything, and a disillusioned and despairing sense of impotent outrage set in.

But now Kaczyński has blinked. Perhaps he realized that these demonstrations weren’t going to just fizzle out, as previous ones had. Perhaps he felt that he had to do something after the protesters entered the churches during mass this past Sunday. Perhaps he is intimidated by strong women and outraged that they would step outside the patriarchal obedience that he expects. Or perhaps he is losing control of both himself and his Party—after all, this is happening just weeks after infighting among his followers brought the government to the brink of collapse.

Regardless, today he gave a speech that was unhinged even by his standards. Referring to the protests, he said that “this attack is an attack that is aimed at destroying Poland. It is supposed to lead to a triumph of forces which, if they gain power, will fundamentally bring to an end the history of the Polish nation.” Those forces, he warned, demonstrated “certain elements of preparation, perhaps even training.” But true Poles need not fear, Kaczyński concluded, because “today is when we must be able to say ‘no’ to all those who can destroy us, but it depends on us, the state, its apparatus, but it depends above all on us, on our determination, on our courage….Let us defend Poland, let us defend patriotism and show our courage. Only then can we win the war that was declared by our opponents.”

If they wish, the PiS government could utilize emergency powers related to the COVID crisis to break up demonstrations. Photographs of the protests show that mask use is near universal, but obviously it isn’t possible to consistently retain social distance at such moments. The pro-choice activists in Poland are facing a dilemma shared by the Black Lives Matters movement in the US: how does one organize a mass movement in the midst of a pandemic? Making things worse, the coronavirus is spiking in Poland, and has now far surpassed the US on a per-capita basis. Polish hospitals are quickly reaching capacity, supplies are at critically low levels, and all signs were pointing to a worsening crisis even before these protests began. In fact, there has been speculation that PiS chose this moment to launch their anti-choice measures precisely because they assumed that protests would be impossible. Clearly, hundreds of thousands of Polish women feel that their reproductive freedoms are worth the risk of COVID.

If a police crackdown against protesters is coming, PiS will try to dampen the international and domestic outcry by appealing to the public health catastrophe. Maybe a different government could get away with that, but PiS can’t. President Andrzej Duda, who himself tested positive for COVID over the weekend, has already said that he would not accept a vaccination even if one was developed, and Kaczyński has been notoriously resistant to wearing a mask. Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki asserted over the summer that Poland would not have another lockdown no matter what happened, though suddenly the government is now suggesting that such a step might be necessary. The credibility of the Polish government on the pandemic is not nearly as bad as the Trump administration’s, but that’s not much of a standard to go by. When this is combined with the authoritarian reputation that PiS has (quite appropriately) gained over the past five years, they have no reservoir of trust to draw upon.

I cannot see a scenario in which PiS remains in power for long if they opt to use violence to break the women’s strike. Of course, they have the means to arrest and intern opposition leaders and use riot police to break up any public demonstrations. Since they control the courts, they could shut down opposition media and even declare martial law. But even the sclerotic Eurocrats could not sit idly by if that happens. If Trump is defeated in next week’s US elections, PiS would lose its last significant international ally. Hungary, Turkey, and Israel won’t be of much help (though Budapest could certainly make it much harder for Brussels to act). Putin is on the sidelines in this story—despite ideological affinities, Kaczyński’s visceral hostility towards Russia has prevented him from following Orbán’s pro-Kremlin foreign policy. Isolated internationally and besieged by the pandemic, Kaczyński will have enormous difficulty surviving a switch from “soft authoritarianism” to a Belarus-style strategy of open violence and oppression.

Going forward, four scenarios are plausible: 1) this crisis brings down the PiS government and leads to snap elections; 2) somehow PiS figures out how to wriggle out of this mess by returning to the abortion “compromise,” and Kaczyński comes up with a way to back away from today’s incendiary speech; 3) the protesters prove unable to sustain the protests beyond a few more days, and we return to the status quo ante; or 4) the government does indeed use force against the protests, despite the inevitable domestic unrest and international isolation that would follow.

Whatever happens over the coming days, this is by far the greatest crisis PiS has faced. The consequences of decisions made now will reverberate for years to come.

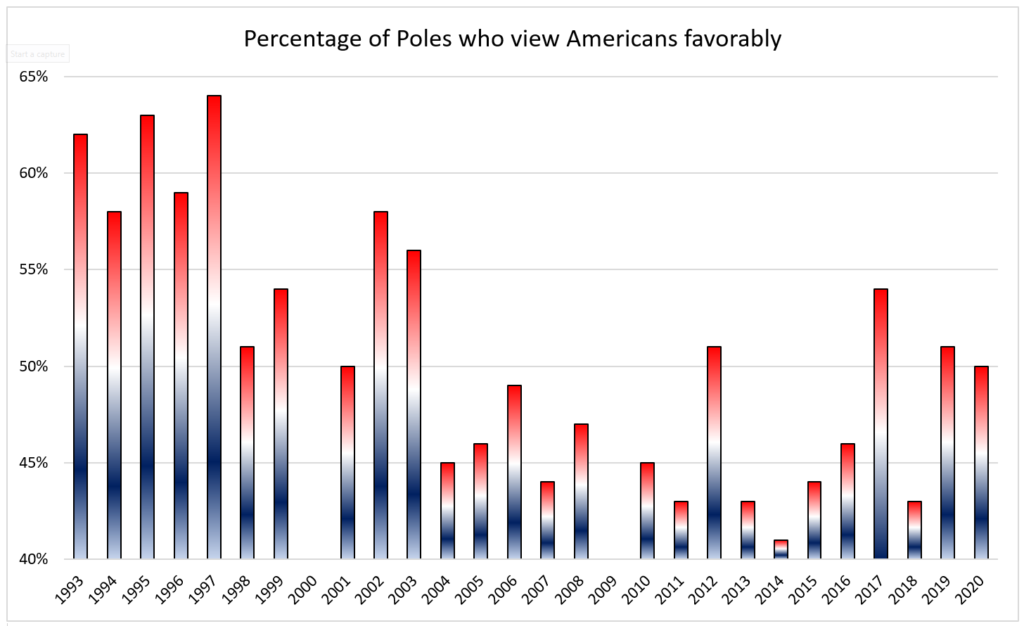

After arguing for years that we should stop treating Poland as an exotic, “backward” corner of Europe, I may have finally found something that is truly unique about that country: Poland may be the only place in the world where people have a higher opinion of Donald Trump today than they had in 2016.

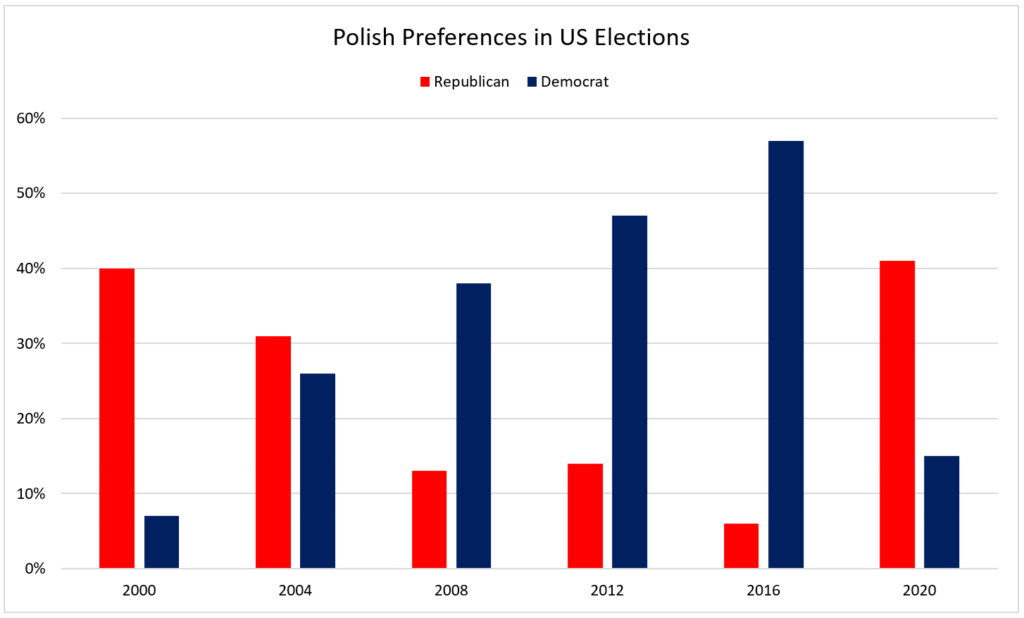

A survey just released today by the Centrum Badania Opnii Społecznej (CBOS, which goes by the name “Public Opinion Research Center” in English) revealed who Poles considered the best candidate for the US presidency, from the point of view of Polish interests. 41% chose Donald Trump, and only 15% picked Joe Biden. Another 15% said that either would be fine, and 29% did not know.

Contrast that with a survey carried out four years ago, in which 57% of Poles polled (eventually I was going to use that phrase) supported Hillary Clinton, and only 6% (!) supported Trump. Another 14% thought either would be the same, and 23% didn’t have an opinion. Where else in the world has Trump’s approval rating increased by 35% over the past four years?

A couple interpretations of this bizarre data come to mind. First, it might reflect a Machiavellian assessment in which the key phrase is “from the point of view of Polish interests.” As long as the far-right Law and Justice Party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, or PiS) governs Poland, having an ideological ally in Washington will help the country, unless you define “help” as “help save us from PiS.” It is doubtful that Poland would be discussed much in a Biden White House, given the monstrous domestic challenges the administration would face upon taking office. However, US relations with the EU would improve dramatically and relations with Russia would sour. Despite the ostensible anti-Russian stance of PiS, an American turn against Putinesque authoritarianism would inevitably sweep up Turkey, Hungary, and Poland. If even the Trump-appointed US ambassador was willing to publicly attack the PiS government’s homophobic bigotry, one can only imagine that criticism from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue (or at least al. Ujazdowskie 29/31 in Warsaw, where the US Embassy is located) would intensify. The past four years of fraternal right-wing warmth between Washington and Warsaw would fall into a deep chill, akin to Poland’s dismal relations with Brussels.

An opponent of PiS in Poland might cheer such a development, but that is a risky attitude. A Biden administration might put pressure on Poland that would constrain some of ambitions of PiS leader Jarosław Kaczyński (particularly regarding his campaign against the independent media, given that the opposition television channel TVN is owned by an American corporation). But I doubt the State Department would take any initiatives against PiS—that’s a job for the EU. Meanwhile, official propaganda in Poland could stoke hostility against yet one more enemy. This idea is not as improbable as it might seem: thirty years ago, Americans were more beloved in Poland than just about anywhere else, but despite an uptick recently, we’ve been finding less and less affection along the Vistula. It would not be difficult to revise the tirades against the Western decadence of the EU to include the US as well. I’m sure Mr. Putin would be happy to stoke those fires, should the occasion arise.

Another interpretation of the strange contrast between 2016 and 2020 might be a straight-forward case of ideological affinity. Four years ago the Polish press was depicting Donald Trump as a buffoon with no chance of winning the election; meanwhile, Hillary Clinton was relatively well known as Secretary of State, and the Clinton name had a lingering glow from those years of pro-American sentiment in the 1990s. Particularly after Trump’s visit to Warsaw in 2017, where he gave an address that could have been written by PiS speechwriters, he was adopted by the Polish far right as one of their own. If we consider that current support for PiS is almost identical to the support now given by Poles to Donald Trump, this makes sense.

As to Biden’s lack of popularity, that might be a result of simple unfamiliarity. Polish media coverage of the United States is certainly more comprehensive than American media coverage of Poland, but it would be unreasonable to expect that a US Vice President would be a household name. It is easy to imagine that a Bernie Sanders candidacy would have generated a lot of excitement, particularly on the Polish left. Though this has rarely been noted, Sanders would have been the first Polish-American president (his father was born in Słopnice in Małopolska, and emigrated from Poland in 1921). Biden, in comparison, is largely an unknown. So we might be dealing with ideological excitement on the right, combined with either apathy or a lack of knowledge among everyone else.

The one interpretation I need to debunk is that Poles, being so conservative, are prone to support Republicans. It is true that Ronald Reagan has a statue in Warsaw, and that Polish-Americans tend to vote Republic. There was a vague impression in Poland in the 1990s that the Republicans had been the “hawks” vis-à-vis the USSR, while the Democrats had been more “dovish.” This impression changed in the 21st century, particularly during the presidency of George W. Bush. He recruited Poland to support the American campaign in Iraq in exchange for a promise to lift visa restrictions for Poles. Not only did the Iraq campaign come to be viewed as a disastrous quagmire in Poland, but the visa rules were never changed. So prior to this year (again, according to a series of CBOS reports over the years), there has been a dramatic shift in the Polish attitudes towards US political parties.

It is certainly possible that 2020 will lead to a reversion to the patterns of the 1990s, but I can’t think of any reason why this would be the case. If I am correct that unfamiliarity is a key reason for the low score received by Joe Biden, we could expect a rapid shift in attitudes if he wins the election. Not a turn to an imbalance in the opposite direction, but more likely an alignment that would more closely mirror the ideological divides within Poland itself. If it comes to pass that Poles view American politics through their own ideological prisms, this would actually be something new. I’ve repeatedly had conversations with Polish leftists who admire Ronald Reagan, and the stunning support for Clinton in 2016 shows that she was likely getting favorable ratings by people who voted for PiS. Given an increasingly globalized politics, and increasing political polarization within Poland, I don’t anticipate such a disconnect to persist much longer.

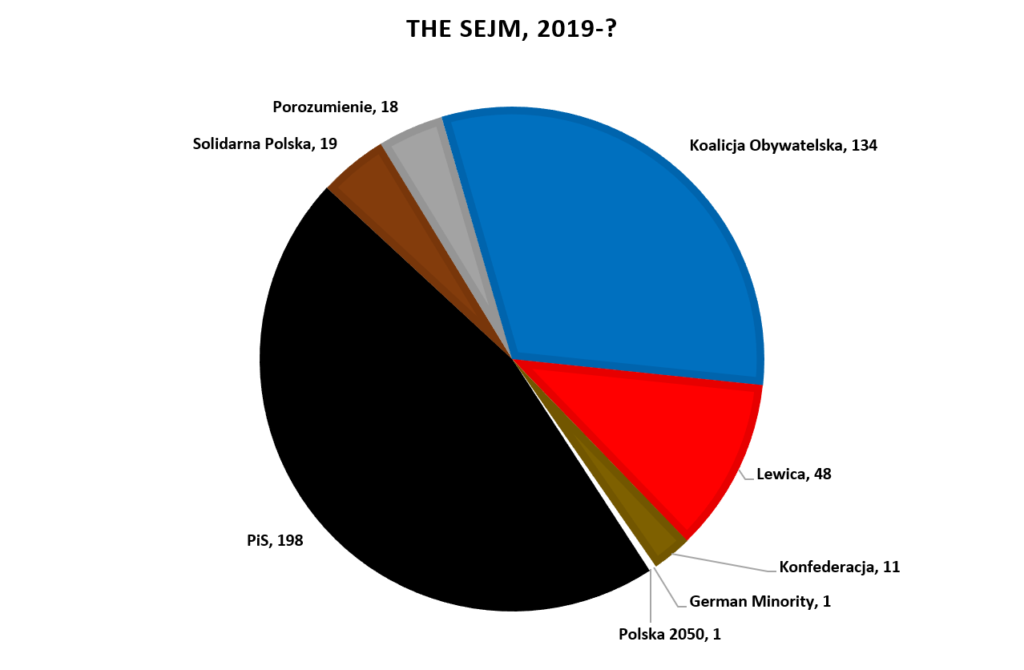

Whenever I pretend to be a pundit I usually end up humiliated (Andrzej Duda never had a chance to defeat Bronisław Komorowski, PiS couldn’t do too much damage because they lacked the votes to change the constitution, etc.). But it seems that I may have gotten something right, despite my best efforts. After the elections last fall, I argued that it was going to be very difficult for Kaczyński to sustain discipline and unity within his own camp going forward. The Zjednoczona Prawica (United Right) had really been “PiS, etc.” during the first term, but the elections changed the landscape by increasing the strength of the other right-wing parties, Zbigniew Ziobro’s Solidarna Polska and Jarosław Gowin’s Porozumienie (Agreement). The former consists of ideological hard-liners who resent what they see as compromises made by PiS. For Ziobro, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki is just a technocrat, and not a true believer. On the other side, Gowin casts himself in the Christian Democratic tradition, though he is far, far to the right of Angela Merkel. Perhaps a better parallel would be the Republican party of the US, as it was in its pre-Trump iteration. In other words, Porozumienie advocates social conservatism (what Americans would recognize as a “family values” agenda) combined with a commitment to private business and free markets.

It was easy to forget that Solidarna Polska and Porozumienie even existed as separate entities during PiS’s first term. After last October, however, they increased their parliamentary strength vis-à-vis PiS. If we broke out the three members of the (up until now) United Right, the current balance of power in the Sejm would look like this:

In recent weeks the tensions between Kaczyński, Ziobro, and Gowin have been bubbling to the surface. First came the controversy over the presidential elections, which were originally scheduled for May. Kaczyński wanted to push ahead with the original timetable despite the COVID crisis, using a hastily put together vote-by-mail system, under the management of a newly-appointed postmaster loyal to PiS. The opposition challenged the legitimacy of this sudden change in voting procedures, but more surprising was the fact that Gowin did as well. He insisted on a postponement of the election, and when it became obvious that PiS alone did not have the votes to push forward, the vote was indeed delayed. Andrzej Duda won anyway, though it was much closer than it would have been in May. Gowin actually appeared to be standing on principle: he believed that a victory under those conditions would not be seen as legitimate. He was probably right, and he may have saved Kaczyński from himself. Anyway, in the aftermath of this Gowin lost his position as vice-premier, even though his party technically remained part of the ruling coalition.

As the summer came to an end, the three parties were negotiating about a reconfiguration of the government—a common process after an election, even when the incumbents win. It was reasonably certain that Morawiecki would continue as prime minister, but the balance of the ministerial posts given to the coalition members was in question. This is where the story gets indecipherably complicated, and I won’t even attempt to lay out the many personal conflicts that have been in play. The short version is that Ziobro wanted more authority, and was positioning himself to either 1) merge with PiS and establish himself as Kaczyński’s heir; or 2) build Solidarna Polska so that it could stand alone as an independent party to PiS’s right. Gowin, meanwhile, wanted to get back into government, but on his own terms. Needless to say, Kaczyński wanted to put these two upstarts in their place. Both as a matter of personality and as a matter of ideology, Kaczyński does not tolerate dissert. The foundation of his belief system is that the nation must speak with one voice, and that the state should be disciplined and cohesive. His vision of democracy is that people vote for a leader, and afterwards the losers get in line behind the majority. There is no such thing in his worldview as a “loyal opposition,” which is why he has routinely described his opponents as traitors, foreign agents, criminals, etc. He has paid homage to Carl Schmitt’s idea that politics is about “us” and “them,” and that the ultimate goal was to subordinate others, not compromise and negotiate with them. Given this, there was never any chance that Kaczyński would calmly go forward making deals in order to get his desired legislation passed. In fact, for him any piece of legislation, any state policy, was a secondary concern behind the need for unity and discipline.

Two issues brought the conflict to the surface. First, a law backed by PiS that would give government officials immunity from prosecution for any violations they committed in the course of fighting the COVID epidemic. There are already officially filed charges against Morawiecki for his role in the aborted May election, in which a number of constitutional provisions were violated in the attempt to change the voting procedures. One might think that this is irrelevant, since the primary project of the past four years has been to subordinate the judiciary to political control – a project which has mostly succeeded. Yes, the court system is now largely subject to the will of the Minister of Justice, but that happens to be none other than Ziobro, who despises Morawiecki both personally and ideologically. It is an open secret that Ziobro has been using his position to collect information that he might use someday against Morawiecki and other PiS politicians. Not surprisingly, then, Ziobro does not want the law on immunity from prosecution to go forward.

Meanwhile, this week it was time to vote on a law that was a pet project of Kaczyński himself: a set of new rules to protect animal welfare. It might seem like a small-scale issue over which to break a coalition, but it gained symbolic weight because of the context. The main provisions of the bill would ban the killing of animals for fur, and put a stop to the practice of slaughtering animals without stunning them first in order to reduce their pain. The latter provision would put an end to both kosher and halal slaughter, which is actually a pretty big deal. Although there is are only miniscule Jewish and Muslim communities in Poland, an increasing number of very profitable firms have been exporting to the Middle East, and to Jewish and Muslim communities in Europe. One might have expected there to be antisemitic or Islamophobic overtones to this issue, but as far as I can tell that is not the case. Interviews with both Muslim and Jewish butchers, and the public rhetoric surrounding the bill, seem to indicate that this is indeed an animal welfare measure. Throughout Europe there is a popular view, usually found on the left rather than the right, that ritual slaughter is cruel. Setting this debate aside, by all accounts it is this belief that motivated Kaczynski’s bill.

To make an already long story a little less long, let’s cut to Thursday. The bill came to a vote, and PiS declared that it would enforce party discipline. Despite that, 38 member of PiS, including even the Minister of Agriculture, voted no. Gowin’s supporters abstained. The measure passed anyway, because most members of the opposition supported it (how’s that for irony?).

The past few days have been tumultuous, to put it mildly. Kaczyński has complained that “the tail is trying to wag the dog,” referring to Ziobro’s power grab. Leading members of PiS have said that the coalition is now finished, leaving only two alternatives: a minority government, or snap elections. A minority government would be, in effect, a caretaker administration. It would be nearly impossible to realize Kaczyński’s ambitious second-term plans, above all his goal to muzzle or eliminate Poland’s still vibrant independent media. Snap elections, on the other hand, would probably be disastrous for the right. Taking an average of the past month’s surveys, the entire United Right has 40.8% of the vote. Unfortunately we don’t yet have polling that separates out the three parties of the governing coalition, but it is an open question whether Ziobro and Gowin could independently gain the 5% needed to win seats in the sejm. Perhaps Solidarna Polska could, but Porozumienie certainly could not. Either way, this would leave PiS alone with results in the low 30s at best. Meanwhile, the main parties of the center and left currently have 47% of the vote, though one of them (PSL) is close enough to the 5% mark to raise concerns. In other words, the results of snap elections would be very hard to predict, but the most likely outcome would be that PiS’s rule would come to an end.

I’m feeling very nervous even writing that last sentence. To be clear: I do not think that this is the most probable outcome of the crisis, because I cannot believe that Kaczyński, Ziobro, and Gowin would allow things to get that far. Still, over the past several days the rhetoric has become quite heated between them, and even more so between rank-and-file members of their parties. I think all three have overplayed their cards disastrously (from their perspective), and walking this back will be impossible. My guess is that they will try, but even if they do, there is no longer a united coalition governing Poland. Every piece of legislation will involve careful vote-counting and hard lobbying.

Whatever happens next, the days when the sejm was just a rubber stamp for Kaczyński’s have come to an end.

I cannot recall an election in my lifetime that hasn’t been described as a turning point, with the very future of life-as-we-know-it at stake. Sunday’s presidential elections in Poland are no exception, but in reality the potential disaster is much greater for one side than the other.

For supporters of liberal constitutional democracy, there is a chance that Sunday will bring the end (or at least the beginning of the end) of a long nightmare. If the liberal mayor of Warsaw, Rafał Trzaskowski, wins the presidency, the monopoly on power enjoyed since 2015 by Jarosław Kaczyński’s Law and Justice party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, or PiS) will come to an end. They would still control the government, the lower house of parliament, the courts, the police, and the public media—so there’s that. But the president could henceforth veto legislation and delay or even block a whole range of appointments. In a normal political system this would be a setback but not a defeat, but we are not talking about a normal political system.

Kaczyński is not likely to earn a “plays well with others” badge. Ideologically he is an admirer of Carl Schmitt (as demonstrated here, here, here, here, here and complicated somewhat here), and he sees politics as a battle for power between “us” and “them,” in which constitutional constraints are irrelevant. One of his favorite terms is “imposibilizm,” which he uses to refer to the claim that certain things cannot be done merely because they are illegal or unconstitutional. He does not consider politics to be a space for compromise, deliberation, and consensus; instead it a battle in which rivals are subordinated and the will of the leader is established. He labels expressions of dissent in parliament as the ravings of a “chamska hołota” (roughly “redneck rabble”) and he recently argued that Poland requires a “national agreement” that would silence an opposition that merely “defends the old order, defends the privileges of the so-called elite, and longs to subordinate Polish interests to foreign influence.” He has demonstrated again and again that he cannot tolerate politicians who treat him as an equal and question his decisions. He doesn’t care about specific policies but about building of a system in which the principle of leadership will reign. Passing this or that piece of legislation is meaningless for him if it can only be achieved through negotiation and compromise.

Given Kaczyński’s worldview, it is unlikely that he will long tolerate a system of divided government, and if Trzaskowski wins on Sunday, there’s a good chance that snap parliamentary elections will follow. Andrzej Duda has been the ideal president for Kaczyński, because Duda has virtually no power-base of his own and cannot act independently. In fact, he is so isolated, personally as well as politically, that it is unclear what he might be able to do with his life after the presidency. The fact that I’ve made it this far in this essay without mentioning Duda’s name is not an accident: calling him a puppet of Kaczyński is an insult to the agency of marionettes. Needless to say, Trzaskowski would not be so obedient, so a victory for the opposition in Sunday’s elections would be intolerable to Kaczyński. We have to add to this the psychological component. Jarosław Kaczyński continues to believe that his late twin brother, Lech Kaczyński, was destined by History to hold the presidency, and even Duda’s occupation of that post is painful for him. A representative of the “redneck rabble” would be unbearable.

So Trzaskowski’s victory would likely start a cascade of political crises. It won’t be pretty, and I would never bet against Kaczyński’s ruthlessness when it comes to a struggle for power. The only certainty is that a system of divided government will not function if Kaczyński is one of the players.

The deeper problem for PiS is that even a victory by Duda will not resolve much. There have been abundant signs of internal conflict among supporters of the government, and even clearer indications that PiS will never establish a cultural hegemony in Poland that will match its political power. Kaczyński’s authoritarian peers, like Viktor Orbán or Vladimir Putin, control not only their country’s institutions, but they have used that position to build strong majorities of public support. Kaczyński remains the most distrusted politician in the country, with a disapproval rating of 66%. He actually manages to make Donald Trump (with a mere 55.8% disapproval rating) look popular. This has always been so; the success of PiS has depended on his ability to hide from public view and convince voters that his puppets are independent political leaders (which they are not). Now, with the economy in deep trouble and with Poland the only European country (aside from Sweden) that has failed to suppress the coronavirus, PiS would be very unlikely to repeat the thin parliamentary victory it achieved last October.

The vote this Sunday will be extraordinarily close. The most sophisticated statistical modeling shows that Trzaskowski’s likely result will be between 48.49 and 52.82% while Duda’s will be between 47.18% and 51.51%. This gives Trzaskowski an 80.3% chance of victory. Most pundits, meanwhile, think that Duda has a slight edge. I suspect that both of these prognoses are correct: Trzaskowski is likely to win slightly more votes, but Duda has an edge because PiS controls the voting process. Explicit fraud will be hard for them to pull off, but small-scale “irregularities” reinforced by a compliant judiciary—that’s well within their ability.

A victory by the opposition would be perceived as a catastrophic, even apocalyptic result for Kaczyński and his die-hard supporters. And they would be right: divided government has no place in their political universe. A victory for Duda, meanwhile, would be a blow for the opposition, but it might not prevent the unraveling of PiS rule.

In Erich Maria Remarque’s famous novel, All Quiet on the Western Front, the title is intended to be ironic. The daily slaughter of WWI trench warfare was such that if “only” a few thousand people were killed on a given day, the news would report it as uneventful. As we reach the climax of a tumultuous presidential election in Poland, I have a similar feeling. For five years I’ve been writing the same story: the governing Law and Justice party (PiS) constitutes an existential threat to constitutional democracy and the rule of law, only a minority of Poles approve of what they are doing, they will likely win yet another election anyway, and the results will be catastrophic. The war of Poland against Poland continues—all quiet on the eastern front.

At first glance, the results of the first round of the presidential elections last Sunday, June 28, appeared to be a decisive victory for the incumbent, Andrzej Duda (PiS). At second glance, one can see reason for the leading opposition candidate Rafał Trzaskowski (the center-right Civic Platform, or PO), to be hopeful. At third glance, the sense of doom returns.

Duda’s victory in round one was decisive: with 43.5% of the vote, he was far ahead of the 30.5% that Trzaskowski received. If we assume that turnout in the second round is the same as the first round, then Duda needs to get another 1,262,218 votes in order to get past 50%, while Trzaskowski would have to find more than three times as many: 3,795,391. Despite that imbalance, however, Duda might face the more difficult challenge. Nearly all of the 2,693,397 votes that went to the third-place candidate, Szymon Hołownia, will go to Trzaskowski. In fact, Hołownia has already endorsed his former rival, despite having once compared the difference between the PiS and PO candidates as “between having one’s house burn down and breaking one’s arm.” The candidate of the Left, Robert Biedroń, has also urged his supporters to vote for Trzaskowski, though this would only add a meager 432,129 people to the PO candidate’s total. Most of those who identified with the Left already cast their ballots for Trzaskowski in round one, thanks to Biedroń’s lackluster and at times inept campaign. Meanwhile, none of the eliminated candidates will endorse Duda, who has a very strong base with PiS supporters but very little beyond that. If we add up all the votes of the opposition, and all those that went to Duda, then it becomes clear that the PiS government is quite far from a majority.

But then comes our third glance. Among those who voted for losing candidates in the first round, there are almost two million whose views and values are not represented by either Duda or Trzaskowski. Władysław Kosiniak-Kamisz was the candidate of the agrarian party, PSL. The 459,365 votes he received in the first round came as a crushing blow, considering that back in April it seemed plausible (albeit unlikely) that he would make it to the second round. The PSL is bitterly opposed to PiS, since both compete for the same rural voters. On the other hand, those who vote for PSL might not feel that same rivalry. They tend to be devout Catholics, and thus unlikely to support a cosmopolitan, urban figure like Trzaskowski. During the campaign, Duda has leaned heavily into his homophobic worldview, expressing views that have elicited an outspoken denunciation from around the world. In response he said that he could not be homophobic, because “in the presidential palace I am often visited by people who have a different sexual orientation than mine. That is not the slightest problem for me.” While such lines provoke derision in Warsaw, Poznań, Wrocław, and Gdańsk, his earlier claim that LGBT rights were “worse than Bolshevism” and his description of sex ed as “experimenting on children” could earn him some support from a portion of the PSL electorate.

An even bigger wild card is the fourth-place candidate, Krzysztof Bosak, who represents a new party called Konfederacja. As the name suggests, it is an alliance of several small far-far-right movements. Bosak offers a nationalist, xenophobic, antisemitic, misogynistic, and homophobic intolerance that goes beyond what even PiS would accept. They oppose PiS because they think the current government is insufficiently resolute, but Konfederacja voters would seem to be a likely source of extra votes for Duda. However, another tone within the discordant cacophony that is Konfederacja consists of radical libertarians. They look upon PiS as fundamentally unacceptable because of the generous social welfare programs that have been introduced in the past five years. As Bosak said after the first round, “Andrzej Duda uses free-market slogans, but he has signed 30 laws that have raised taxes.” To put this in American terms, Duda is akin to Steve Bannon, while Bosak is more like Rand Paul. Aside from these ideological differences, Bosak understands that if his small party is to have a future, PiS has to lose. Only if Jarosław Kaczyński is dethroned as the leader of the right will there be space for alternative right-wing parties This helps explain why pre-election surveys found that fewer than two thirds of Bosak’s voters would support Duda in round two.

If we put all these numbers together we get around 9.3 million votes for Duda…and around 9.3 million votes for Trzaskowski. Ensuring that their supporters get to the polls will be crucial for both candidates, and in this regard the well-oiled party machinery of PiS gives them a distinct advantage. On the other hand, Poland’s worsening COVID crisis will be a major problem for a party that draws its support disproportionately among older voters. If the election were just dependent on votes of people under 30, then Trzaskowski would win by almost 5%, but if only those over 60 voted, Duda would win by almost 30%. If those with just an elementary school education picked the winner, then Duda would get over 70%, but if just those with higher education voted, his total would fall to 26%. If we assume that those with more education are more likely to participate in the election, then Trzaskowski will have an advantage. It’s going to come down to a very small number of votes, one way or the other.

Pointing out hypocrisy is usually pointless: first, because we are all guilty of this sin from time to time; second, because it is rare indeed when someone who is confronted with their own inconsistencies responds by abandoning mutually exclusive viewpoints. More commonly, they (we, because I do this too) just rationalize our views until the round peg really does fit into the square hole.

That said, I have to make an exception today, because the double standard is so glaring and so upsetting.

With protests against systemic racism and police brutality breaking out across the United States, someone in Poland decided to show their solidarity (something Poles are supposed to be good at) in a particularly poignant way. In both Lafayette Square in Washington and Żelazna Brama Square in Warsaw stand identical statues that symbolize the bond between our countries. The figure commemorated in these monuments is Tadeusz Kościuszko, who is one of those rare historical figures who really does deserve to be (literally) placed on a pedestal. He is most famous for serving as a volunteer in the American army during our War for Independence, and then for returning to Poland to lead an uprising against Russian rule.

He is famous for his service during these wars of national liberation, but that is not what truly set him apart from his contemporaries on both sides of the Atlantic. In both the infant American Republic and in the dying Polish-Lithuanian Republic, he stood out boldly for his opposition to unfree labor. In Poland he was responsible for the very first effort to eliminate serfdom, with the justly famous Połaniec Manifesto of 1794. This document, which sadly remained a dead letter because of Kościuszko’s eventual defeat, recognized peasants (the vast majority of the population of northeastern Europe at the time) as full citizens with equal protection before the law—a radical proposal at that time. More, shortly after issuing this document Kościuszko also promised to implement a program of land reform that would give peasants full property rights over that land that they cultivated. To translate this to an American context, this would be as if an antislavery abolitionist had demanded that the white landowners divide up their plantations for distribution to former slaves.

Kościuszko also carried these values to North America. In his will, he dedicated a large part of his estate, including the substantial sum he had earned serving as a high-ranking officer under Washington, to the cause of purchasing manumission for slaves. In keeping with his program for unfree laborers in northeastern Europe, he specified that the newly freed African-Americans be provided with land, tools, and whatever education they might need to be successful. Unfortunately, he had the poor judgment of naming Thomas Jefferson as the executor of his North American property, and he refused to carry out his Polish friend’s wishes.

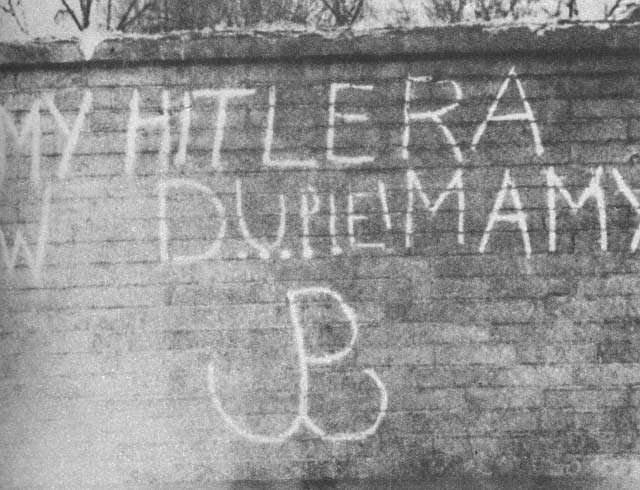

With this background, I cannot imagine a more appropriate gesture than this, which appeared last week on the Warsaw monument to Kościuszko:

Currently the mayor of Warsaw, Rafał Trzaskowski, is running for president as the candidate of the liberal opposition. He has generated a great deal of hope recently among those who want to bring an end to the far-right nationalist rule of the Law and Justice Party, and their apparatchik currently serving as president, Andrzej Duda. In the past Trzeskowski has positioned himself as the candidate of multicultural tolerance, and was even willing to alienate his more centrist supporters by defending LGBTQ rights. In response to the Kościuszko graffiti he said “There can be no acceptance for vandalism. I have ordered the cleaning of the Tadeusz Kościuszko monument in Warsaw, which was devastated (zdewastowany) last night.”

Here are some of the headlines the next day:

One of those headlines is from the absurdly tendentious state television, which serves as the party organ of Law and Justice. Another is from Polsat, a commercial station that usually tries to position itself as nonpartisan. The third is from Gazeta Wyborcza, which is the leading newspaper for the center-left opposition. Can you guess which is which? I cannot think of another occasion in which picking between these three would be difficult.

Meanwhile, an official state body known as the Institute for National Memory is currently selling a celebratory album called Graffiti in the Polish People’s Republic. The website culture.pl (the English language site of the Adam Mickiewicz Institute) offers an article entitled “Playing with Censorship: How Polish Artists Dealt with the Communist Regime”. The featured image on the article is a bit of graffiti that reads “the radio and the TV belong to the nation! Down with censorship!”

It is still possible to find fading street art in Warsaw that dates from the communist era, and there have been efforts to have these included in the “registry of historical artifacts” so that they can be preserved.

And of course, the famous “Fighting Poland,” the symbol of true patriotism, began life on the walls of Warsaw.

I’m not arguing that the Black Lives Matter slogan written on the Kościuszko monument be preserved and sanctified. Personally, I probably would have chosen another way to link the slogan with its very deserving Polish progenitor. But given the long history of the effective use of street art as a form of protest in Poland, the nonpartisan rush to condemn this powerful and appropriate political statement as if it was merely an act of “vandalism” or “destruction” may well be the most glaring act of hypocrisy in our all-too-hypocritical age.