Final Results

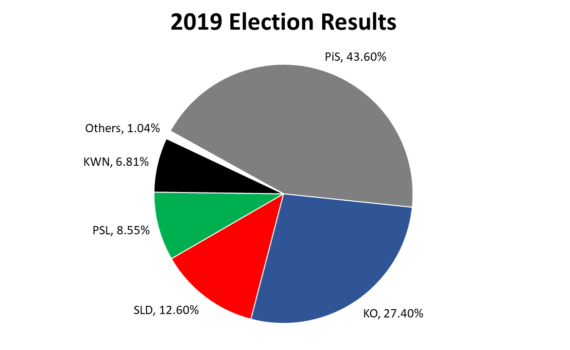

The votes have been counted, and the picture hasn’t changed much from last night. In percentage terms, the exit polls turned out to be reliable:

If we look at the raw numbers, we see that the three parties supporting the basic norms of constitutional democracy got more votes than PiS, but fewer than PiS and KWN together.

Under different rules for apportioning the parliamentary delegates (for example, the Webster/Sainte-Laguë method used in Poland in the 1990s, as opposed to the d’Hondt method used today), PiS would not have been able to form a government without entering into a coalition with KWN – something that might have been impossible because of the latter’s close ties with Putin. As it is, however, PiS did just barely pass the 231 seats needed to govern without any coalition partners.

At first glance it might seem that little has changed. In the previous parliament, PiS also had 235 votes, and Civic Platform (the main party within the Civic Coalition) had 138. But in reality, quite a lot has changed. The social democrats were entirely shut out in 2015, and PSL only had 16 seats. In their place was a large liberal party known as Nowoczesna (literally “Modern”), ideologically similar to Civic Platform but with a slightly stronger emphasis on free market economics and secular politics. That party is now gone, having re-merged with Civic Platform to create (along with the Greens) the Civic Coalition. Meanwhile, on the right, the previous parliament had 42 members belonging to a strange party called Kukiz 15, an eponymous creation of the rock star Paweł Kukiz that drew upon nationalist and far-right imagery, but concentrated mostly on countercultural opposition to “the system” in general. Kukiz himself has joined with PSL, and in his party’s place is a more ideologically committed extremist party, KWN, which combines radical libertarianism, misogyny, homophobia, antisemitism, xenophobia, racism, and open hostility to the EU (and a corresponding fondness for Russia). In other words, Jarosław Kaczyński now faces a genuine (albeit small) challenge on his right flank, and a liberal-democratic opposition that has moved significantly to the left. Previously, PiS could position itself as the populist defender of the welfare state against free-market liberals. That will no longer be the case.

None of this matters if Kaczyński continues to follow the take-no-prisoners, scorched-earth politics that he has used over the past four years. Previously, he just rammed through his legislative agenda with no regard to the opposition, abolishing the process of developing new laws through public parliamentary committees. He went so far as to limit debate to absurdly short sessions, allowing the opposition no time to offer more than brief soundbites leading up to a ritualistic vote. Parliament itself became irrelevant, because everyone understood that the real decisions were made in the PiS party headquarters.

Real power will remain in Kaczyński’s office, but the deployment of that power is going to be much more difficult than it has been so far, thanks to the results of yesterday’s election to the senate, Poland’s upper legislative house. Here the entire center and center-left opposition agreed to a slate of candidates—not quite a coalition, but a promise not to compete against each other. As a result, the outcome more closely matched the overall distribution of popular support, and PiS lost control of the upper chamber.

I’ve included in the chart above one nominally independent candidate who is supported by PiS, and three independent candidates who are supported by KO.

With 51 votes, the opposition will be able to control the senate, which could have huge consequences. In the past, the senate has received little attention, because it has few powers. It cannot originate legislation, and its veto power over the lower house could be overridden with ease, requiring only an absolute majority. With the seats in the lower house as closely divided as they now are, Kaczyński is going to have to pay close attention managing the legislative process, and there is suddenly space for maneuvering that he thought he had closed down. Just as important, a veto from the Senate blocks implementation of any new legislation for 30 days, so the whole system will now move with a deliberate pace, giving the opposition time to mobilize when necessary. Finally, the approval of the senate is needed for any referenda, as well as for the appointment of several vital government positions: the National Ombudsman, the chair of the Institute for National Memory, and above all the “Rzecznik Praw Obywatelskich” (Civil Rights Advocate). The latter official is charged with monitoring the government’s adherence to the constitution, and is empowered to bring the government to court in cases of violation. This has been an irritant to PiS for the past four years, though because of their control over the judiciary they have been able to neutralize the office’s power. Nonetheless, the existence of such a figure, along with the anti-corruption monitoring of the National Ombudsman, offers at least some independent monitoring.

All of this helps us understand the mood among Polish politicians today. The expectation before last weekend had been that PiS would win decisively—in fact, Kaczyński was openly hoping for a so-called “constitutional majority” (enough votes to revise the constitution). Now, his party lacks even enough votes to override a presidential veto. Of course, for the time being that’s a moot point because President Andrzej Duda is a loyal soldier in Kaczyński’s army. But his term expires in less than a year, and if today’s results are any indication, his reelection is far from certain. The presidency in Poland is decided in a two-round voting system, with the top two candidates from the first round proceeding to the second. Even if we assume that PiS can maintain its 43% support (a high point for that party), will it be able to get the additional 7+ points needed in a head-to-head matchup with the opposition? That’s a very open question.

This is why the mood at PiS headquarters today was subdued, even angry. The body language of Kaczyński over the past 24 hours has been unmistakable, and his speeches have been far from triumphant. He told his audience yesterday that “it is time for reflection;…a time to improve how we are seen by society; a time to eliminate all those things which hinder our possibilities. We have to remember that we are a formation that deserves more. We got a lot, but we deserve more.”

Those words captured Kaczyński’s frustration, but they also constitute a clear threat. In the coming months we can expect a concerted campaign to “eliminate” everything that stands in his way, everything that (in his view) prevented the Polish people from appreciating his greatness. He has itemized these hindrances many times: the cultural “elites,” the judiciary, any independent officials or agencies within Poland (including local self-government), EU oversight, and above all the independent media.

PiS still has power, and it would be naïve to imagine that they won’t use it to the utmost. The opposition is a bit stronger than it was last week, but it still lacks the means to block Kaczyński’s plans. We can expect the regime to become more openly repressive than before, as it attempts to shut down or marginalize the opposition media and strip city and provincial governments of their autonomous power. Kaczyński does indeed believe that his party “deserves more,” and he will do whatever he can to get more. But he is now in a bind: if he pushes his authoritarian measures vigorously, he will risk alienating centrist voters in the run-up to the presidential elections. If he moderates his ambitions, he will leave the opposition with significant platforms from which to challenge his authority. Moreover, PiS has been able to capitalize so far on an unprecedentedly strong economy, but most signs point to a recession on the horizon. Can the party retain support in the mid-40s in the face of an economic downturn? Finally, the EU has indicated that it is henceforth going to take a much harder line on the erosion of liberal democracy among members states.

Kaczyński might think he deserves more, but it is more likely that he is on a path to eventually get what he truly deserves.