We Deserve More

In my post yesterday on the final results of Poland’s parliamentary elections, I mentioned in passing Jarosław Kaczynski’s speech from Sunday night, in which he declared that it was now “time to eliminate all those things which hinder our possibilities. We have to remember that we are a formation that deserves more. We got a lot, but we deserve more.” He went on to say that the Party’s strategy going forward would be to “commit to even better work, to new inventive ideas, and to przyjrzenia się the social groups who did not support us.” The key term in that last sentence is ambiguous; it means “look into” or “study” or “monitor” or “observe” The implied threat, however, is clear enough. As a reporter for the opposition newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza put it, that statement “made my hair stand on end, because what will that “przyjrzenia się” look like?” The answer was there in Sunday’s speech, when Kaczyński said that “the elites, who work for our enemies, are stigmatized. And ladies and gentlemen, they will be stigmatized further.” As I wrote last week, the PiS party platform for this election confirmed that their primary goal was to undo the work of those who governed Poland since the fall of communism, because of the conviction that “abandonment of loyalty to the Polish state by a considerable part of the elite is without a doubt a major characteristic of the system created after 1989.”

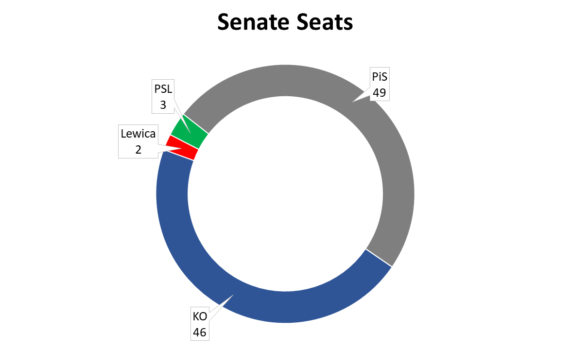

Lest there be any doubt about the implications of this rhetoric, Kaczyński gave another speech after the final results were announced on Monday, and it became evident that the opposition had taken control of the Senate. He insisted that this was not a concern, because “we could have a tie in the Senate today, if we wanted to remove the individuals who from our point of view do not deserve to be there….We will work to ensure that the Senate in fact becomes a place where the war, which is so destructive for Polish politics, will be contained or prevented.”

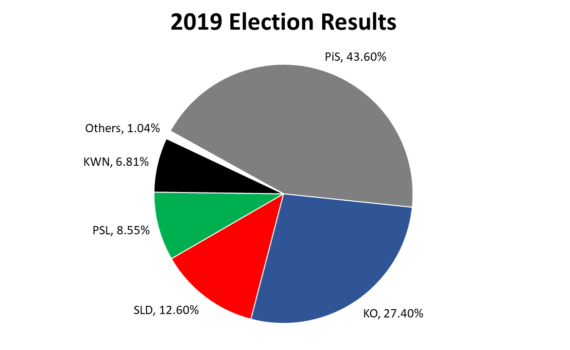

The coming months will be extraordinarily dangerous for Poland’s opposition, yet the leaders of all the opposition parties were surprisingly cavalier this past weekend, seeming to care more about maneuvering among themselves and shoring up their own power bases within their organizations. The left showed unqualified excitement at regaining parliamentary representation after four years in the wilderness, because their 12% showing will provide them not only with enhanced political prominence, but a much larger budget thanks to the 11.4 million złoty (about 3 million dollars) in state subsidies they will now receive. The leader of the Polish Peasant’s Party, Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz, breathed a sigh of relief because the PSL’s respectable showing will quash challenges from party rivals. Conversely, Grzegorz Schetyna, the head of the centrist Civic Platform party is now facing calls to step down because his party failed to significantly increase its support.

Pardon my language, but what the fuck!

I get it. I myself succumbed to cautious optimism in my blog post yesterday. Under the normal rules of politics, the politicians of the opposition parties would have reason to be somewhat pleased by their better-than-anticipated showing yesterday, and they could feel bolstered by their control of the Senate and their increasingly good odds of winning next year’s presidential election. But haven’t they learned since 2015 that PiS does not play by the normal rules of politics? The leaders of the opposition now have targets on their backs, and Kaczyński is a wounded bear (or better, a wounded duck) who has already started to lash out at his “enemies.”

After the 2015 elections, I wrote with some relief that the results were not too bad, because PiS lacked the super-majority needed to change the constitution, thus preventing them from following in the footsteps of Victor Orbán in Hungary. Back in those simpler times, I didn’t imagine that Kaczyński would simply ignore constitutional constraints, defy legal requirements, and proceed with his plans. That is precisely what he did, announcing repeatedly that he needs to break the independence of the judiciary in order to set the groundwork for his further ambitions. Since PiS controls all the mechanisms of power in Poland, they can do whatever they want. There are only three real constraints: the very slim possibility that the EU will someday decide to enforce democratic standards among members states, the possibility of public protest of a sufficient scale and duration, and the desire (so far) of Kaczyński to avoid looking too dictatorial.

The elections of 2019 were, by all accounts, honestly counted, though because the state media is now a propaganda mouthpiece, we should not characterize the campaign as unblemished. It is wonderful that Polish commentators and politicians continue to take free elections for granted, but if Kaczyński wanted to steal an election, he has all the power he needs to do so. And if he decides to arrest a couple senators on trumped-up corruption charges, as implied by his statement yesterday, no one could stop him. Of course this would violate the principle of parliamentary immunity, but there is no longer enough judicial independence in Poland to allow anyone to hope that the courts would step in to prevent such a move.

I really want to be wrong. I underestimated PiS’s willingness to abandon legal constraints in 2015, and maybe I am overestimating their willingness to do so now. Maybe Kaczyński really does believe in the whole package of “illiberal democracy,” the theory of which is based on periodic free elections, but unquestioned and unconstrained central power between elections. Given what he has said over the past 48 hours, however, I would not want to bet on this. I don’t think Kaczyński would stop at anything if he thought he could get away with it.

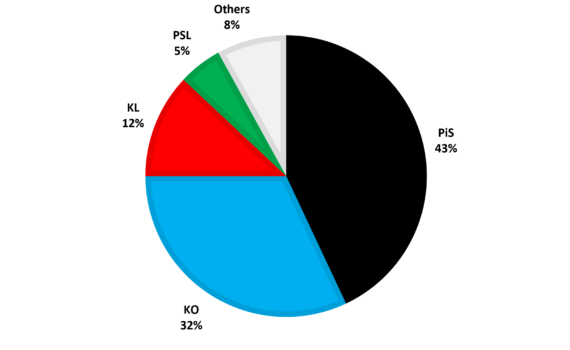

The upshot of this is that the consolidation of authoritarian rule in Poland henceforth will not be prevented by the one-vote majority that the opposition has in the Senate. Nor can they assume that if they run a good campaign and win the presidency next year, PiS will simply accept defeat and move on. These institutional hopes will only work if 1) the EU continues to do little more than issue toothless expressions of disappointment at PiS’s constitutional violations; 2) surveys continue to show PiS support in the high 30s or low 40s; and 3) protests against constitutional violations continue to mobilize crowds in the thousands or tens of thousands (rather than hundreds of thousands). In the absence of a dramatic wild card like a deep recession, I don’t see points 2 or 3 changing. There might be some hope that point 1 will change, but it is concerning that Ursula von der Leyen, the incoming president of the European Commission, had to depend on Polish and Hungarian support to win her position, and has shown signs that she understands the consequences of this.

Life will doubtlessly be more complicated and stressful for Kaczyński in the months ahead, whatever happens. The only remaining question is whether and how he decides to resolve that complexity.