Black Monday

Here’s what Warsaw’s “Black Monday” protest looked like from my very wet perspective within the crowd.

The view from above was much more impressive (courtesy of Gazeta Wyborcza and Fakt.pl).

For an English language account of the day’s events, click here. In brief, this protest was a response to a proposed law that would completely ban abortion in Poland, except when the life of the mother was at stake. The demonstration was the culmination of a day that the organizers labeled a “women’s strike,” evoking an example from Iceland from the 1970s, when everyday life was brought to a halt by a massive work stoppage by women (on the job or within the home).

Estimates for the size of the crowd range from around 25,000 to over 100,000. I’m inclined to believe the larger figure, because people were constantly coming and going, and the total number of participants would have been much higher than the number present at any given moment. Anecdotally, I’d estimate that about half the people walking around downtown Warsaw throughout the day yesterday were wearing black in support of the protest. As to the strike itself, it’s harder to evaluate its impact. Here in Warsaw, a lot of women stayed home, though my impressionistic sense is that most of them did so by taking advantage of authorized personal time – not quite a “strike” in the classic sense of the word. I’d be interested to know how many people defied employers during this action, though I suspect the number would be small. In other words, this wasn’t a labor action, but a political protest in which (many? most?) employers supported their employees, implicitly or explicitly.

The response by the government was captured best by Foreign Minister Witold Waszczykowski, who showed his contempt for the protesters by saying “let them have their fun. If someone thinks that there are no greater concerns in Poland, then go right ahead.” He insisted that “women’s rights are in no way threatened.”

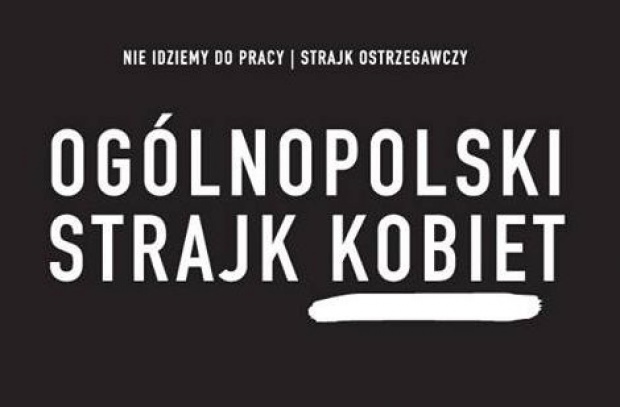

That reaction illustrated the divide brought forth by yesterday’s events. In a seminal article from 1997, Janine Holc argued that the abortion debate in Poland was (at the time) configured in a way that made it very difficult for women as women to claim agency; they could only do so if their appeals were couched in generic categories of liberal citizenship. Is this still true two decades later? The (mostly hand-made) signs I saw yesterday would suggest otherwise, insofar as the vast majority used the rhetoric of women’s rights: “My uterus is my concern,” “Get your hands off of women,” “my body my choice,” “freedom for women,” etc. The poster announcing the strike described it as “The Women’s General Strike” with the underline in the original.

This approach is made more complex by the backdrop of Poland’s ongoing political crisis. Yesterday’s protest would have resonated differently, I think, had this been a “normal” case of a conservative government cracking down on abortion rights. But the Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, or PiS) regime is anything but normal, and the proposed anti-choice legislation is part of a much broader assault on liberal democracy itself. With that in mind, there are two possible paths forward.

In one scenario, it is easy to imagine the regime using the abortion issue to drive a wedge between feminists, liberals, and moderate conservatives. Jarosław Kaczyński has shone a fondness for the methods once used by Poland’s communist authorities to neutralize political opposition, and he is definitely familiar with the divide-and-conquer “salami tactics” famous from the late 1940s. He understands that no single, issue-oriented protest march can challenge his rule, since he has control of the parliament and the presidency, and is almost finished with his plan to neutralize and subordinate the judiciary. Even a steady surge of separate demonstrations would (at most) reduce the popularity of the government, but everyone in Poland is coming to recognize that popular support is irrelevant when faced with unchecked political power. Yesterday’s protest came on the heels of another huge march last weekend by doctors and nurses, and separate emergency meetings of the professional organizations of judges, school teachers, and historians. But do any of these, taken alone, pose any real threat to the regime?

Alternatively, the mobilization of all these disparate forces could coalesce, perhaps under the umbrella of the Committee for the Defense of Democracy (KOD). If a united front of all those opposed to PiS is able to unite in acts of civil disobedience that will genuinely challenge the state, disrupting the ordinary functioning of the government, then there is hope.

I have long insisted that PiS does not represent “Poland,” and yesterday’s events underline this fact. Their support continues to hover around 30%, and if elections were held today they could potentially form a coalition that would approach 40% of the electorate. The problem is that the opposition remains as fragmented as ever, and the anti-PiS parties likely to pass the minimal 5% threshold would probably only constitute about 33% of the vote. If we added up all the political parties opposed to PiS, they would win more votes than all the political parties potentially allied with PiS, but as things stand, most of those votes won’t count because they are scattered among several small parties. In other words, the partisan political scene does not auger well for those who want to bring back the world in which issues like the abortion debate can be fought out within the civic institutions of liberal democracy. To get to that point, there needs to be a lot more work aimed at building alliances among groups that have only sporadically shown any tendency to coordinate their actions.