Tags : Kaczyński KOD PiS

Continuing my effort to make the voices in current Polish debates available to an English-speaking audience, here is a text from the Committee for the Defense of Democracy that summarizes their opposition to the PiS government. As with my previous translation of PiS texts, you are free to use this as long as you credit the source.

The Committee for the Defense of Democracy

http://komitetobronydemokracji.pl/w-obronie-demokracji-w-polsce-by-znow-o-nia-nie-walczyc/

Translated and Annotated by Brian Porter-Szűcs

Ireneusz Doman Domański , “In Defense of Democracy.” (January 18, 2016).

Dear Europeans, Dear Citizens of the United States of America,

Maybe somewhere in France, Portugal, Great Britain, Germany, Romania or Czechia, in the USA or in some other free and democratic country, you are with some surprise asking the question: what’s going on in Poland? Why are those Poles once again taking to the streets? What do they want?

I am not surprised by your surprise. After all, it might seem that nothing happened. A new president was democratically elected, a party with the lovely name Law and Justice took power in democratic elections. It has a majority in both houses of parliament, it has formed its government. Normal stuff.

So why, in November of 2015—that is, right after the elections—Krzysztof Łoziński, a writer, columnist, and member of Amnesty International who is known in his country as a figure from the period of struggle against the communist dictatorship, declared on the website Studio Opinii that it was necessary to create a Committee for the Defense of Democracy.

Why, within a few days after his call, KOD began to take form spontaneously and energetically, first on Facebook, and then in genuine reality? Why have the defenders of democracy received the support of Lech Wałęsa, Nobel Prize winner, legendary leader of Solidarity, former president of Poland? Why did thousands begin to sign up on mass? And why did thousands take to the streets throughout the entire country, in order to demonstrate and protest?

Łoziński wrote in his text, “the question often arises, what should one do when faced with open attempts to tear down democracy?” Yes, there’s a lot of evidence that step by step democracy is being torn down here, and Poland risks being pushed to the margins and, in the near future, isolation. As a result of democratic elections, a right-wing group bearing left-wing postulates has risen to power. It is challenging the accomplishments of the past quarter century in my—in our country. The country that I am proud of. The one that that gives pride to many of my fellow Poles in Europe and around the world.

What else, other than poisoning or outright tearing down democracy, is paralyzing the Constitutional Tribunal, the pillar and guard of democracy in every democratic country?[1] How else can one label questioning the rulings of the Tribunal and refusing to honor them? Pushing through parliament at night (often at four in the morning!) legislation widely considered by constitutional experts and all sorts of legal organizations to be unconstitutional? The legally and morally dubious “suspension” by the President of legal proceedings against an indicted politician of his party, so that he can become a government minister and direct the special services?[2] President Andrzej Duda has a law degree, and he is both a graduate and a faculty member of the academically respected Jagiellonian University. The law department of JU has already repudiated his actions!

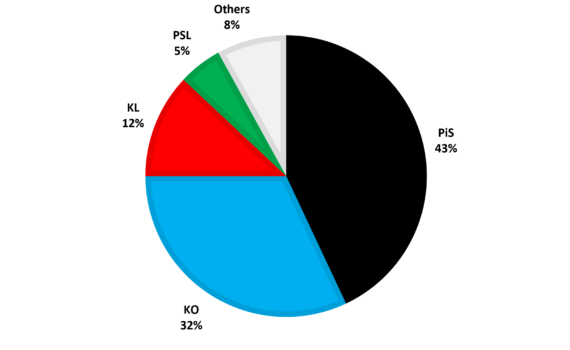

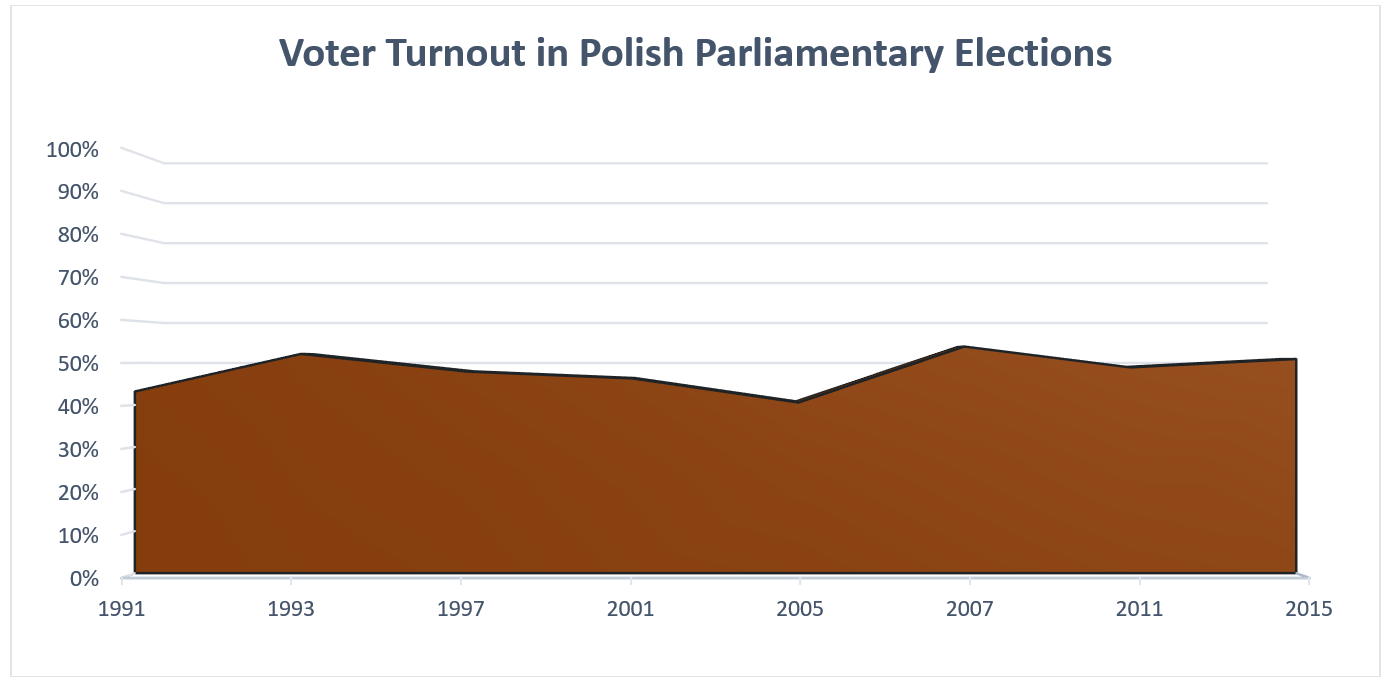

Politicians from the government camp talk about placing Donald Tusk, the former Premier of Poland, and current head of the European Commission, on trial.[3] The Vice-Premier and Minister of Culture attempts to influence the repertoire of the theaters.[4] Representatives of the government proclaim that the will of the nation is above the law, above the Constitution! They proclaim that they have a mandate based on the will of the nation in order to do whatever they want. There have been calls to arrest the Chairman of the Constitutional Tribunal if he does not surrender, and does not subordinate himself to the newly imposed principles of applying the law. I should inform you, therefore, that the group currently in power got the votes of 18.7% of Poles eligible to vote.[5] That is a mandate to govern, but not to appropriate the country, not to nullify the Constitution that was accepted in a national referendum. That is not a mandate to change the system.

In the Polish parliament the opposition is stripped of its voice. They repeat a vote or change the composition of a parliamentary commission, if it so happens that the results are inconvenient for the current government. Delegates from the opposition receive drafts of important legislation at the last minute before debate, without any chance to become familiar with them. All their suggestions and corrections are rejected. Legislation is voted on in haste that allows the government to assume control over the public media and carry out a purge in the editorial boards of the radio and television.[6] There are plans for legislation that would allow widespread surveillance and control over the internet and mail.[7] The nonpartisan civil service is being liquidated so that party functionaries can be named to all positions.[8]

Can you imagine this in your countries? In Great Britain, Germany, Portugal, Czechia, or the USA? ….

This is why KOD exists, modeled on the Committee for the Defense of the Workers (Komitet Obrony Robotników, or KOR), which a was active in my country during the times of the communist dictatorship. I come from Radom. A city, where in June 1976 there was a massive rebellion of workers against the communist party, brutally repressed by the militia. Then the workers in Radom burned down the building of the central committee of the party that had the word “workers” in its name. To defend the people imprisoned and repressed in my city, KOR was created. Jacek Kuroń, one of its leaders, a person with the best opposition bona fides, said then “don’t burn the committee headquarters! Create your own committees!” We did just that.

And since the threat to democracy in my country is real, KOD quickly became a mass movement. A movement that not only does not question the results of the democratic elections, but respects it. We will not burn down any committee headquarters. We are not aggressors. We stand against the aggressors, in order to stop them.

Mateusz Kijowski, the leader of our movement, the Committee for the Defense of Democracy, wrote our manifesto on November 20:

Democracy in Poland is threatened.

The activities of the government, its disrespect for the law and for democratic norms, has forced us to express our decisive opposition.

We to not want a totalitarian Poland, closed to those who think differently than the government commands. We do not want a Poland full of frustration and demands for revenge.

We want Poland to be a place for all Poles, equal before the law, with their convictions, opinions, ethics, and aesthetics.

We do not accept the appropriation of the state, the division of Poles between better and worse, contempt for “others.”

We also do not accept views detrimental to the principles of democracy and human rights.

We are determined to speak openly and decisively, with a loud voice, about decency, law, and mutual respect. To express our opinions not only at home and on the internet, but also on the streets and the squares of our cities and in the countryside, if the need arises to gather there to express our opinions and our demands.

We invite everyone for whom the values of democracy are important, without regard to political views or faith, to join us.

We do not accept violations of the Constitution and the introduction of an authoritarian government through the abuse of democratic mechanisms.

There are among us people of various viewpoints and political orientations, from right to left, believers, agnostics, and atheists. We are united by the fact that we are free people, and we want to continue to live in our own democratic country, in which no one will tell us how to live and what values to hold.

Signed: The Committee for the Defense of Democracy.

In December, 2015, the BBC asked Polish president Andrzej Duda about the anti-government demonstrations that the Committee for the Defense of Democracy organized in many Polish cities. “Those demonstrates consist mainly of those who used to govern Poland and were removed from power by the Polish voters in parliamentary elections,” said Andrzej Duda. He added that those people do not want to accept this fact, therefore—the President said—they are inciting society and organizing demonstrations.[9]

This is the narrative of those currently governing Poland. Thus spoke Jarosław Kaczyński, the chairman of the party that created the government. He is himself a rank-and-file parliamentary delegate, and formally is not responsible for anything. But he is the one who calls us “the worst kind of Poles”[10] He is the one who, commenting on the protests, said that some Poles cooperated with the Gestapo (sic!), and others with the Home Army, the Polish underground army during the Second World War.[11] His party comrades call us “communists and criminals” who have been cut off from our food supply. People, who cannot accept the loss of power

That is a lie! None of us, none of the thousands of people with the Committee for the Defense of Democracy, nor any of the participants in the demonstrations, lost any power. We never had it. I’m an ordinary Pole who is proud of the success of my country, who has enjoyed its growing (until now) prestige, who greatly values the freedom we fought for years ago, and who is ready to defend that freedom. That brutal language serves to divide Poles, to build walls. The chairman of the group currently in power tries to realize his political vision. He does not have the power to change the Constitution.[12] Therefore he tries to weaken the mechanisms of oversight that protect the law and democracy: the Constitutional Tribunal, the free media, the independent judiciary, and independent prosecutors.[13] In mid December, 2015, Lech Wałęsa said on Radio Zet, “This is leading to misfortune, this will end badly, with fighting; they are driving us to a civil war and therefore, to avoid that, we must prepare structurally and organizationally, and already start gathering signatures for a referendum. If in a referendum there are more votes to end the term of the Sejm than were cast for PiS in the elections, then it would result in physically pushing them aside.”[14]

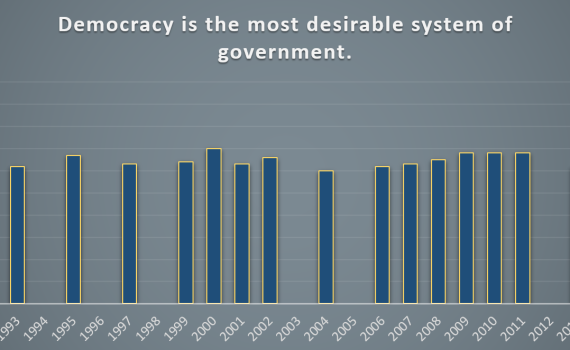

Many, among them politicians from the camp currently governing Poland, have said, “But this is a democracy, since you can demonstrate on the streets.” I answer them: it still is, but you are striking blows against it. But as long as it is, we will defend it, so that you don’t take it from us. Because we do not want to fight for it again, like during those long years before 1989. We did not want to create the Committee for the Defense of Democracy. But we had to. Because we do not want to create a Committee to Fight for Democracy. Unless we must

Then we will.

_________________

NOTES

[1] Shortly before the elections, the previous government filled five vacancies on the Constitutional Tribunal, including two that would not actually be vacated until just after the elections. President Andrzej Duda refused to swear in any of the new justices. A subsequent ruling by the court found that three of the appointments were legitimate, though the previous government had overstepped by trying to replace the other two. PiS has refused to recognize this ruling, and has instead nominated its own replacements to the court. Moreover they have passed a new law governing the operation of the court which requires all decisions to be passed by a 2/3 majority with the participation of at least 13 justices (out of 15 total). The court in turn ruled that law unconstitutional, based on article 190 of the Polish Constitution, which states that only simple majority is required. Law and Justice Chairman Jarosław Kaczyński has said that it was appropriate to block the court from acting because it reflected the priorities of those who wanted to block his reforms.

[2] A reference to the pardoning of Marisuz Kamiński by President Andrzej Duda in November, 2015. Kamiński was the former head of the Anti-Corruption Bureau from 2006-2009, having been appointed to that office during the first PiS administration. He was later convicted of abuse of power, and sentenced to three years in prison. His case was under appeal at the time of his pardon. He is currently a minister-without-portfolio in the government.

[3] PiS believes that Donald Tusk was part of a conspiracy that led to a plane crash on April 10, 2010, which killed the President of Poland, Lech Kaczyński (Jarosław Kaczyński’s twin brother), along with 95 other Polish dignitaries. All the investigations into the disaster (aside from the ones carried out by PiS loyalists) have concluded that the crash was just a tragic accident.

[4] A reference to Minister Piotr Gliński, who attempted to block a theatrical production that he deemed “pornographic.”

[5] PiS won 37.58% of the vote, with a turnout rate of 50.92%: thus the figure of 18.7%. They were able to transform that into a slim majority of parliamentary delegates, mostly because the electoral law in Poland eliminates all parties receiving less than 5% of the vote, distributing their votes proportionally to the larger parties.

[6] In January, 2016, the law was changed in order to eliminate the oversight of the country’s Commission for Radio and Television, instead making all personnel directly subordinate to the Treasury Ministry. In the words of a PiS spokeswoman, “We hope that, at last, the media narrative that we do not agree with will cease to exist.” An independent media does continue to exist in Poland, but the state-owned media dominates the airwaves.

[7] This law was passed, and signed into law on February 4. It was justified by the government as an anti-terrorism measure.

[8] This law was signed into law on January 7. It eliminates previous rules for competitive and open hiring procedures and gives relevant government ministers the authority to hire and fire at will anyone employed by the state.

[9] This interview can be found here.

[10] From a TV interview on December 11, 2014, available on video here, with English-language excerpts here.

[11] From a speech on December 13, 2015, available on video here, with English-language excerpts here.

[12] This requires a 2/3 majority in the parliament, but PiS is far short of that mark.

[13] On January 28, 2016, the Sejm passed a bill that would place all prosecutors under the direct authority of the Minister of Justice, to be hired or fired at will.

[14] This is actually a paraphrase of what Wałęsa said; his precise comments are here.