Jarosław Kaczyński and PiS have become a metaphors for the resurgence of authoritarian nationalism in Poland, but I was reminded today that this is unfair. Without a doubt, Kaczyński and his supporters are attacking the foundations of liberal democracy and promoting a toxic form of nationalism, but occasionally we should step back and ask about the soil out of which PiS grew.

Poles are not significantly more prone to nationalism than anyone else in Europe. This is a point I’ve been making on this blog for a long time. It is highly dangerous to imagine that any particular “culture” is more or less xenophobic, more or less prone to violence, more or less authoritarian. That said, we can identify ritualistic behaviors, mindlessly repeated slogans, and taken-for-granted habits that can either facilitate or inhibit certain ideological movements.

This morning I attended an event at my youngest daughter’s elementary school here in Warsaw. It is highly-regarded public school that does a lot of good work conveying values of tolerance and multiculturalism; it has an well formulated anti-bullying policy that emphases respect for others; and it provides kids with many opportunities for individual creative development. In other words, it looks a lot like the schools I’m familiar with from back in Ann Arbor, Michigan—a town famous for being a bastion of leftist politics and culture. According to the precinct-level results from the last elections, my neighborhood in Warsaw has fewer PiS supporters than is typical for this city, which in turn has far fewer than the national average. Finally, the purges of the educational system that many are predicting have not yet touched this school, and the curricular reforms promised by the government will only take effect next year. In other words, one can’t blame PiS for what is happening at this school (at least, not yet).

In fact, what I observed this morning was a long-standing tradition, and I doubt that anyone would perceive it as political in any way. This was the day when new students take an oath to the school in a formal ceremony—something which struck me as a bit odd, because it wasn’t a custom that I was familiar with. I was expecting the students to pledge to study hard, follow the school rules, never cheat, be kind to their classmates, be respectful to their teachers, etc. Actually, my first reaction was to think that this would be something worth copying back home, because there’s good pedagogical research on the effectiveness of pledges and contracts as a means of reducing academic misconduct (at all levels of education). While there were references to all these irrefutable values at this morning’s pledge, the primary emphasis of the ritual caught me off guard: it was all framed around the promise to be a good Pole, not just a good student.

Much of the event was innocuous, and even delightfully cute. The first graders all marched in to the school gymnasium wearing cardboard mortarboards color-coded for their home rooms. There was excellent singing (I was there because I’m the proud father of a member of the school chorus), and a few wonderfully short speeches. At one point the first-graders recited this poem:

We aren’t afraid of school,

Even though hard work awaits.

We bravely enter the school today

Because the time has come to learn.

We will learn the alphabet,

and then how to read, and write too,

and we will be able to read

every verse by ourselves.

We will also learn to count,

And we will learn about the whole world.

And there will be time for play,

So everyone is happy today!

My daughter informed me that not all the students agreed that this last line was accurate.

But along with all that, there was a separate segment of the event that unsettled me. The school director called out “attention!” much as an army drill sergeant would back in the US, and everyone (including parents) obeyed. The school flag was then marched into the room, after which the director said “at ease.” The children then proceeded to the formal pledge:

I pledge to be a good Pole,

To protect the good name of my class and my school.

I will learn in school how to love the fatherland,

In order to work for it when I grow up.

I will try to be a good friend,

And in my behavior and my studying

Bring joy to my parents and teachers.

I do not know how old this text is, or exactly how commonly it is used today. I did find an alternative version (albeit one from 2005) that has an entirely different tone:

I will always protect the good name of my school.

I will fully take advantage of the time designated for learning.

I will respect the teachers, the school staff, and my classmates.

I will maintain order and cleanliness in class, in the school, and on the playground.

I will take good care of school property.

I will try to get good grades.

There are other alternatives as well, with a greater or lesser nationalist emphasis, but the version I heard at my daughters school appears to be extremely common.

In addition to the oath itself, the students recited a famous poem, the “Catechism of the Polish Child,” written by Władysław Bełza in 1900:

Who are you?

A little Pole.

What is your sign?

A white eagle.

Where do you live?

Among my own.

In what country?

On Polish land.

What is that land?

My Fatherland.

How was it won?

With blood and wounds.

Do you love her?

I love her sincerely.

And in what do you believe?

In the Polish faith

The children shouted out the last line with extra vehemence. Fortunately, they did omit the last two lines from the original:

What are you for [the nation]?

A grateful child

What is your duty to her?

To sacrifice my life.

Finally, the whole room sang a song from 1910 entitled “Rota” (with lyrics by Maria Konopnicka and music by Feliks Nowowiejski):

We won’t forsake the land that our people [ród] came from

We won’t let our language be buried.

We are the Polish nation, the Polish people,

From the royal Piast dynasty.

We won’t let the enemy oppress us.

So help us God!

So help us God!

To the last blood drop in our veins,

We will defend our Spirit.

Until the maelstrom of the Teutonic Knights

Collapses into dust and ashes,

Every doorway shall be a fortress.

So help us God!

So help us God!

The German won’t spit in our face,

Nor Germanize our children,

Our forces will rise up in arms

The Spirit will lead us.

We will go when the golden horn sounds.

So help us God!

So help us God!

We won’t have Poland’s name suppressed,

We won’t step alive into the grave.

In Poland’s name, on its honor

We lift our foreheads proudly,

The grandson will regain his grandfather’s land.

So help us God!

So help us God!

As a historical text, this speaks to the emotions provoked by the oppressive program of Germanization in what is now western Poland during the late 19th and early 20th century. And since then, Nowowiejski mournful, evocative melody has ensured that the song has lived on in the canon of Polish patriotic music. I’m sure that most Poles recite these familiar lines without even thinking about what they mean, which is precisely why they are so disconcerting when heard sung by a children’s choir in 2016. Konopnicka’s own linkage between the German government of her day and the Teutonic Knights already elicits a sense of an eternal menace, and a child learning the words now would be forgiven for assuming that the references remain relevant today.

When all of this is put together, we are left with a picture of a Poland that is eternally under siege by enemies trying to “spit in our face,” and a formulation of the mission of an elementary school as a place where children learn above all “to work for the fatherland.” In case the kids forget, they are greeted every day by this stairway at the entrance to their school:

Nearly every event on this chronology of Polish history is a battle or uprising against one or another of Poland’s neighbors, inter-spaced with a handful of acts of oppression or aggression against Poland. The only exceptions are the references to the baptism of the tribal chieftain Mieszko in the year 966 (described here as the “baptism of Poland”), the Union with Lithuania, the Constitution of May 3, 1791, the re-establishment of Polish independence in 1918, the round table talks of 1989, and the attainment of EU membership in 2004.

None of this will necessarily produce a population of nationalists, no more than does the recitation of the “Pledge of Allegiance” in US schools. And all the references to the “Polish Faith” will not guarantee obedience to the Roman Catholic hierarchy (though on this point, the inclusion of religious instruction in the schools and the crosses hanging in every classroom are sure to have an ongoing impact). The imperfection of cause-and-effect here is demonstrated by the huge recent demonstrations on behalf of liberal understandings of civil rights and democracy, the massive opposition to the Church on issues like abortion, and the even more basic fact that the “victory” of PiS in 2015 came with only 38% of the vote (and a far smaller percentage of the eligible electorate). So to characterize what I’ve described here as “indoctrination” would lead us to wonder why it is so ineffective.

No, none of this is PiS propaganda. This is the just the background noise in Polish cultural, educational, and political institutions that everyone takes for granted and repeats without much thought. But taken together, it does produce a worldview in which the nation must be united in vigilance against eternal foes. To challenge this worldview requires hard counter-cultural work, and far too few members of the political or cultural elite—including, above all, those who are trying to defeat Jarosław Kaczyński—even see the need for such work. Until they do, they will be conceding to PiS nearly all the fundamentals, and squabbling about the details.

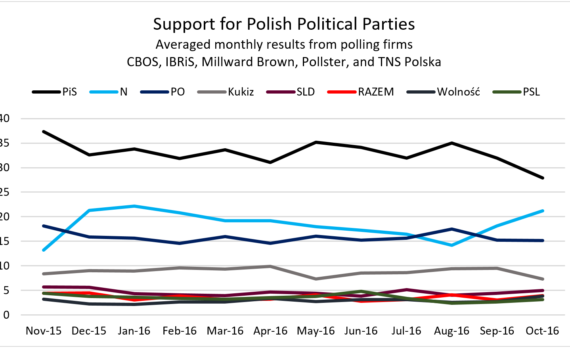

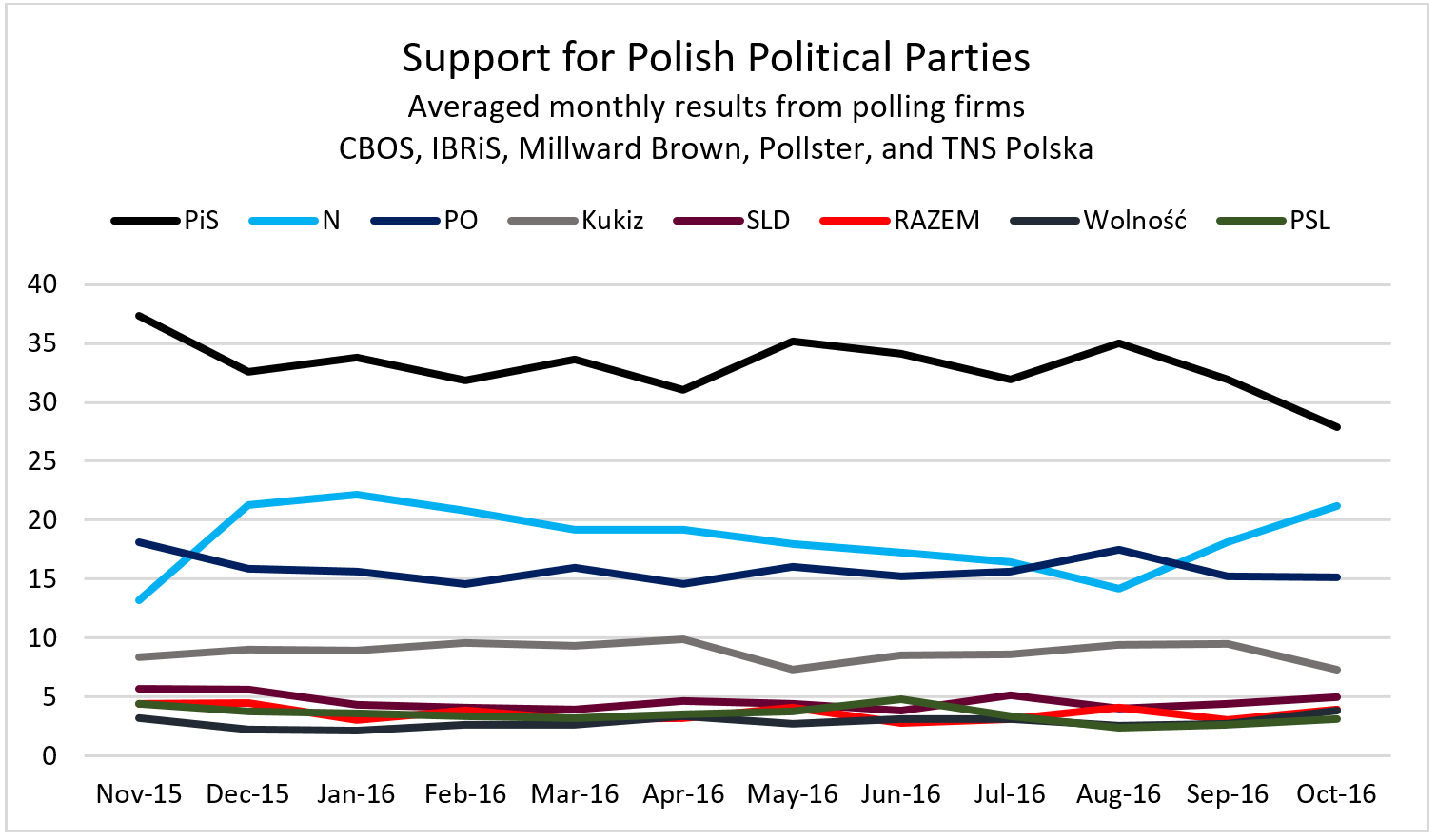

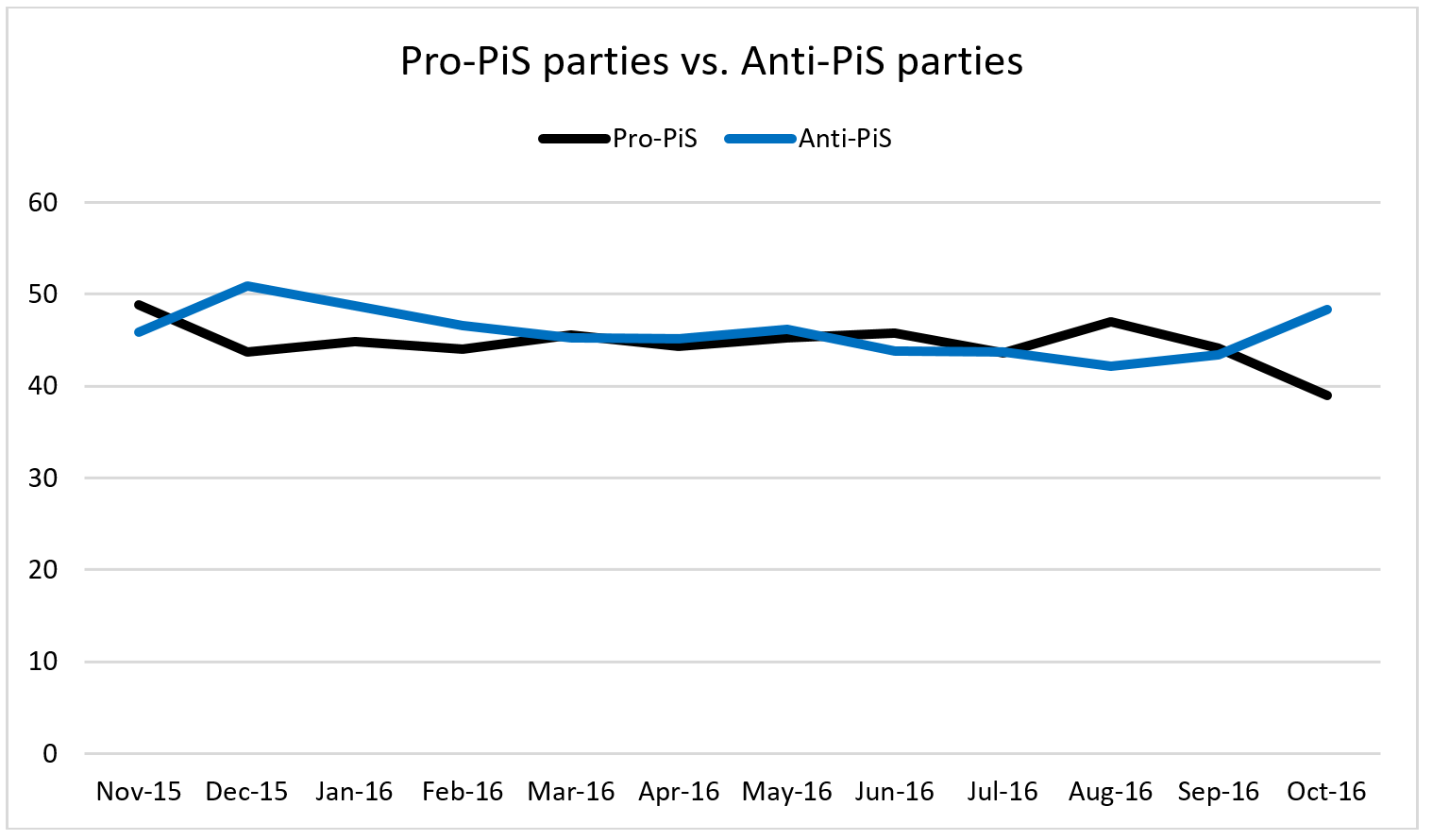

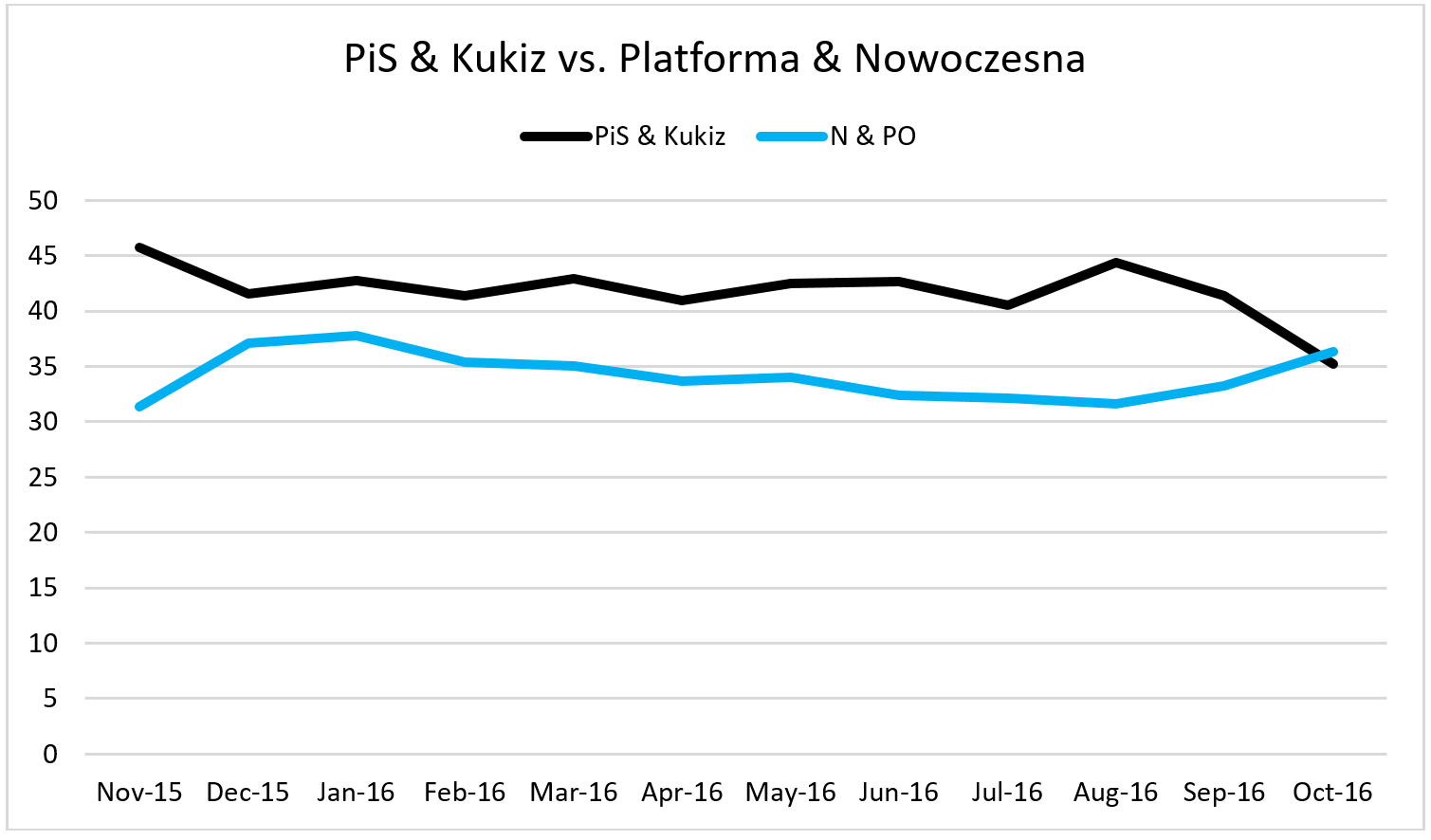

That gives us a good snapshot of the increasingly cavernous divisions in Polish society, but because of the quirks of the Polish electoral law, it isn’t necessarily relevant to the distribution of power in the Sejm. If we remove all the parties that cannot (as of now) pass the 5% minimum needed to get any seats, we would have a simpler lineup of PiS and Kukiz vs. Platforma and Nowoczesna.

That gives us a good snapshot of the increasingly cavernous divisions in Polish society, but because of the quirks of the Polish electoral law, it isn’t necessarily relevant to the distribution of power in the Sejm. If we remove all the parties that cannot (as of now) pass the 5% minimum needed to get any seats, we would have a simpler lineup of PiS and Kukiz vs. Platforma and Nowoczesna.

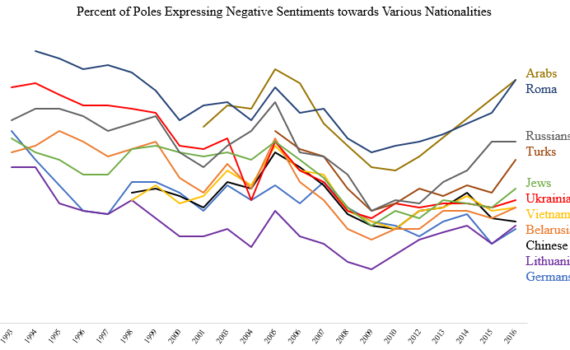

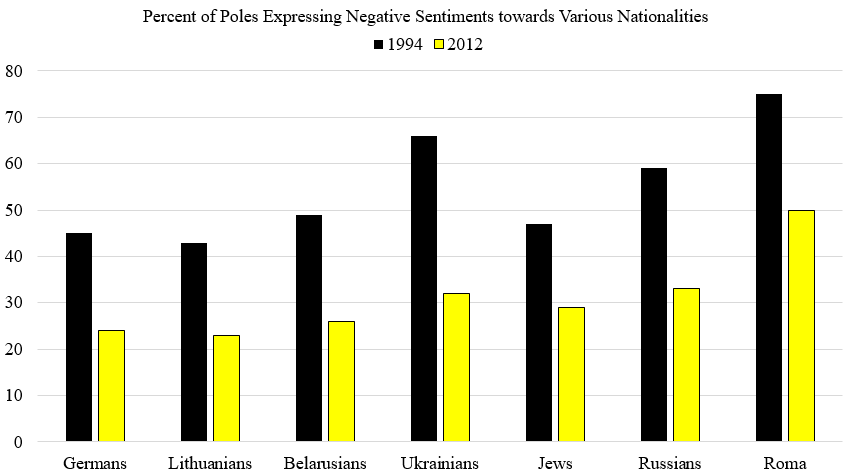

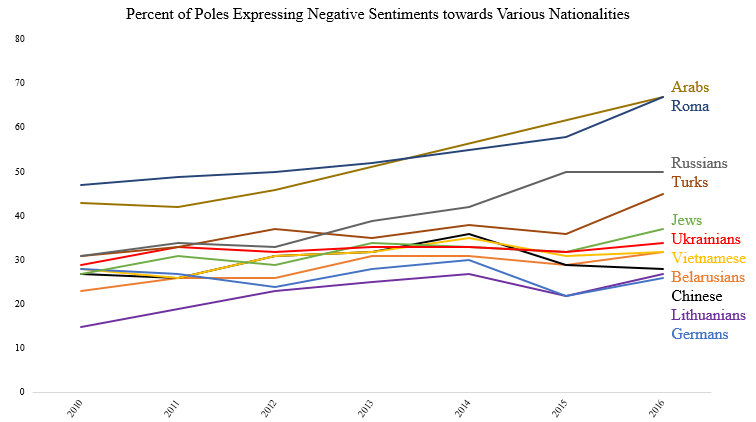

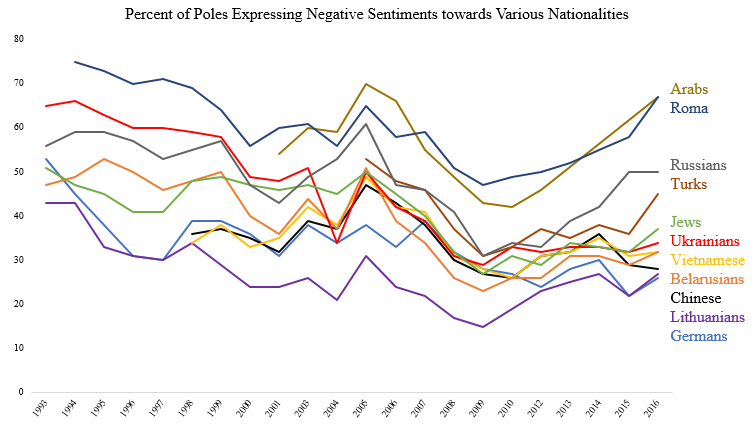

What are we measuring here? Probably not actual sentiments, insofar as people may not be willing to admit to xenophobia or racism if doing so carries a stigma. But I think that is precisely the point: we are witnessing an important shift in what is considered publicly acceptable.

What are we measuring here? Probably not actual sentiments, insofar as people may not be willing to admit to xenophobia or racism if doing so carries a stigma. But I think that is precisely the point: we are witnessing an important shift in what is considered publicly acceptable.