On Thursday, the Polish bishops released a document entitled “The Christian Form of Patriotism” (Chrześcijański kształt patriotizmu). The text, which I’ve partially translated below, has a number of interesting passages which are already being interpreted as a condemnation of the nationalist excesses of groups affiliated with or supportive of the current government. In fact, that is explicitly what the document does, by drawing a sharp distinction between “patriotism” (good) and “nationalism” (bad).

The bishops condemn what they call “national egoism,” a term which has a long tradition in Poland linked to Roman Dmowski and the early-20th century National Democratic movement (big heroes of the Polish right). On a few occasions over the past year, a neo-fascist group called the National-Radical Camp (Obóz Narodowo-Radykalny) has met in churches and had masses said in their honor (see here and here for news about the most recent episode, which Church leaders have already apologized for). Today the ONR had a large march in Warsaw (well, a few hundred people—for them that’s large), and their schedule notably did not include a procession to a local church.

A few more aspects of this newest Church document might also raise some eyebrows. The bishops criticize the exploitation of history for political purposes, the staging of historical re-enactments that glorify war, the use of polarizing rhetoric, the propagation of forms of patriotism that are closed to ideological diversity, and most emphatically the expression of any disrespect for people of other faiths or national background. They even cited Islam in this context, albeit only in passing. In fact, the text has a reference to the need to show “hospitality” to people from other nations, though that’s the closest the bishops came to repeating Pope Francis’ message of support for accepting refugees.

The problem with this document, as with many of the bishops’ writings, is that it is pitched at such a high level of abstraction that readers of different ideological orientations will be able to interpret it to their liking. The text included several references to the use of “unjustified historical analogies,” which supporters of the current government will take to refer to the opposition’s charges that Poland is turning into an authoritarian state similar to those imposed upon this country in the past. Calls for toning down divisive rhetoric will be understood by supporters of the government as a demand that the opposition stop complaining about the ways in which the regime is undermining the constitution and violating fundamental norms of democracy and the rule of law. Indeed, these interpretations are probably appropriate, because it is well known that a large majority of the bishops are supporters of Jarosław Kaczyński’s “Law and Justice” Party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, or PiS).

So the PiS leadership can rest easy: there’s nothing here that will cause them any short-term headaches. They’ll be able to spin the bishops’ letter for their purposes, and since the drafting committee included many supporters of PiS, this isn’t really even spin. There is a clear warning here to Mr. Kaczyński to stop flirting with the furthest reaches of the far right, which could eventually make it harder to him to follow his long-standing policy of not allowing anyone to outflank him on the right. He wants to ensure that the small parties trying to replicate the success of Jobbik (an undeniably neo-fascist party in Hungary) will not succeed, and in that context the bishops have just set a line that they don’t want him to cross. But in reality, it isn’t going to be hard for almost everyone on the right in Poland to read this document, nod their heads in agreement, and say “clearly I’m a patriot, and only those bad people with whom I would never cooperate are nationalists.”

Having said all this, I still think this text might turn out to be important. So far the Church as an institution – and for that matter nearly all priests – have shown unwavering support for PiS. There have been absolutely no signs that any significant members of the clergy, much less the episcopate, are willing to speak out in support of the democratic opposition. There have been some rumors that a few bishops have lobbied unsuccessfully for Kaczyński to soften his anti-immigrant rhetoric, but other bishops have declared openly their opposition to accepting any refugees. The contrast between the Church in Poland and the Papacy could not be more obvious. As the PiS government has neutralized the judiciary, centralized power by abolishing all separation of powers, turned the state media into a vulgar propaganda mouthpiece, and demonized the opposition as traitors and conspirators who care only for undermining Poland’s genuine national interest – throughout all of this, the Church has said absolutely nothing. Against that dismal backdrop, this week’s statement from the episcopate is a slight shift, a baby-step to place a little bit of daylight between the Church and the PiS State.

Anyone expecting the Church to play a role in fighting today’s authoritarianism similar to the one they had during the communist era will be disappointed. That’s just not going to happen. We are not going to see priests (at least, no more than a few renegades) marching alongside the liberals and feminists who have been challenging the PiS government so far.

But this statement by the episcopate suggests that it is possible that the Church leadership would prefer not to be seen as an appendage of the nationalist right. In PiS’s Poland, the Catholic Church is one of the few institutions that Kaczyński (probably) cannot neutralize, and maybe—just maybe—this might serve as a weak constraint that could keep the very worst elements of the radical right from rising to even more power.

That’s not much of a hope. But these days, it might be all we have.

________

Here are some excerpts of the text from the Episcopate. The complete 4,398 word text can be found here)

The revitalization of patriotic attitudes and feelings of national consciousness, which we have observed in Poland over the past few years, is a very positive phenomenon. Love of the fatherland, affection for the culture and traditions of one’s homeland – these things do not just relate to the past, but are tightly bound to our present capacity for sacrifice and solidarity in the attainment of the common good. They therefore influence the form of our future in a real way.

At the same time, we can see in our country the emergence of attitudes that are contrary to patriotism. Their common ground is egoism. This can be individual egoism, apathy about the fate of the national community, exclusive concern for the wellbeing of the individual and those closest to him. This sort of inattention to the treasure that every one of us receives together with our common language, the history and culture of our homeland, connected to an apathy about the fate of one’s countrymen – this is a non-Christian attitude. Also contrary to patriotism is national egoism, nationalism, the cultivation of a feeling of superiority, being closed off to other national communities as well as the human community. Patriotism, after all, must always be an open attitude. As our great countryman Henryk Sienkiewicz one aptly put it, “the slogan of every patriot should be: “through the fatherland to humanity.”

….

From this same Christian perspective, we want to note today that patriotism, as a form of solidarity and love of one’s neighbor, is not an ideological abstraction, but a moral call to give witness to good here and now, in a concrete place, under concrete conditions, among concrete people. Since it is not an ideology, patriotism does not impose a rigid ideological cultural form, and even less a political form, but in diverse ways implants itself and brings to fruition in the lives of people and diverse communities, which want to further, in solidarity, the common good.

Patriotism differs therefore from the ideology of nationalism, which imposes onto living, everyday relations with concrete people, in the family, in school, at work, or at home, rigid diagnoses and political programs often characterized by an aversion to foreigners. They strive to force cultural, regional, and political diversity into a uniform and simplified ideological schema.

….

We want to underline once again the necessity in our fatherland of a patriotism, well known from our history, that is open to cooperation in solidarity with other nations, based on respect for other cultures and languages. Patriotism without force or contempt. Patriotism attuned to the suffering and injustices that affect other people and other nations.

A patriotism for all citizens. Therefore we emphasize and remind everyone that all Polish citizens contribute to the life and development of our fatherland. The history and identity of our fatherland is particularly closely tied to the Latin tradition of the Catholic Church. Nonetheless, alongside the Catholic majority, our common fatherland has been well served, and continues to be served, by Poles who are Orthodox, Protestant, as well as adherents of Judaism, Islam, and other faiths, as well as those who do not find themselves in any religious tradition. And even though the criminal Holocaust carried out by the German Nazis, as well as other tragic events during the II World War and its aftermath, ensured that many of these communities are no longer among us, their contribution will always be inscribed onto our culture, and their descendants continue to enrich our public life.

Therefore contemporary Polish patriotism, remembering the contribution that Catholicism and Polish tradition has made, should always embody respect and a feeling of community with all those citizens, regardless of their faith or heritage, for whom Polishness and patriotism are a moral and cultural choice.

….

At a time of deep political conflict, such as divides our fatherland today, it is also a patriotic duty to work for social unity by remembering the truth about the dignity of every person, by relaxing excessive political emotions, by identifying and expanding the field of possible (and essential for Poland) cooperation across divides, as well as the defense of public life from unnecessary politicization. And the first step that one should take in patriotic service is to reflect on the language with which we describe our fatherland, our compatriots, and ourselves. Everywhere, therefore, in private conversations, in official speeches, in debates, in the traditional media and in social media, we are obligated by the commandment to love our neighbor. Therefore the measure of Christian and patriotic sensitivity becomes today the expression of one’s opinions and convictions with respect for one’s compatriots, including those who think differently, in a spirit of kindness and responsibility, without oversimplification and unjust comparisons.

….

In light of Christian respect for human dignity and also a Christian political vision, it is necessary to recognize as unacceptable and dangerous the exploitation and instrumentalization of historical memory for ongoing struggles and political rivalries. Wherever conflicts (quite natural in politics) become saturated with hasty political analogies and when historical arguments replace economic, legal, or social reasoning, then it sometimes becomes impossible to reach political compromises that are honorable and essential to a democratic society.

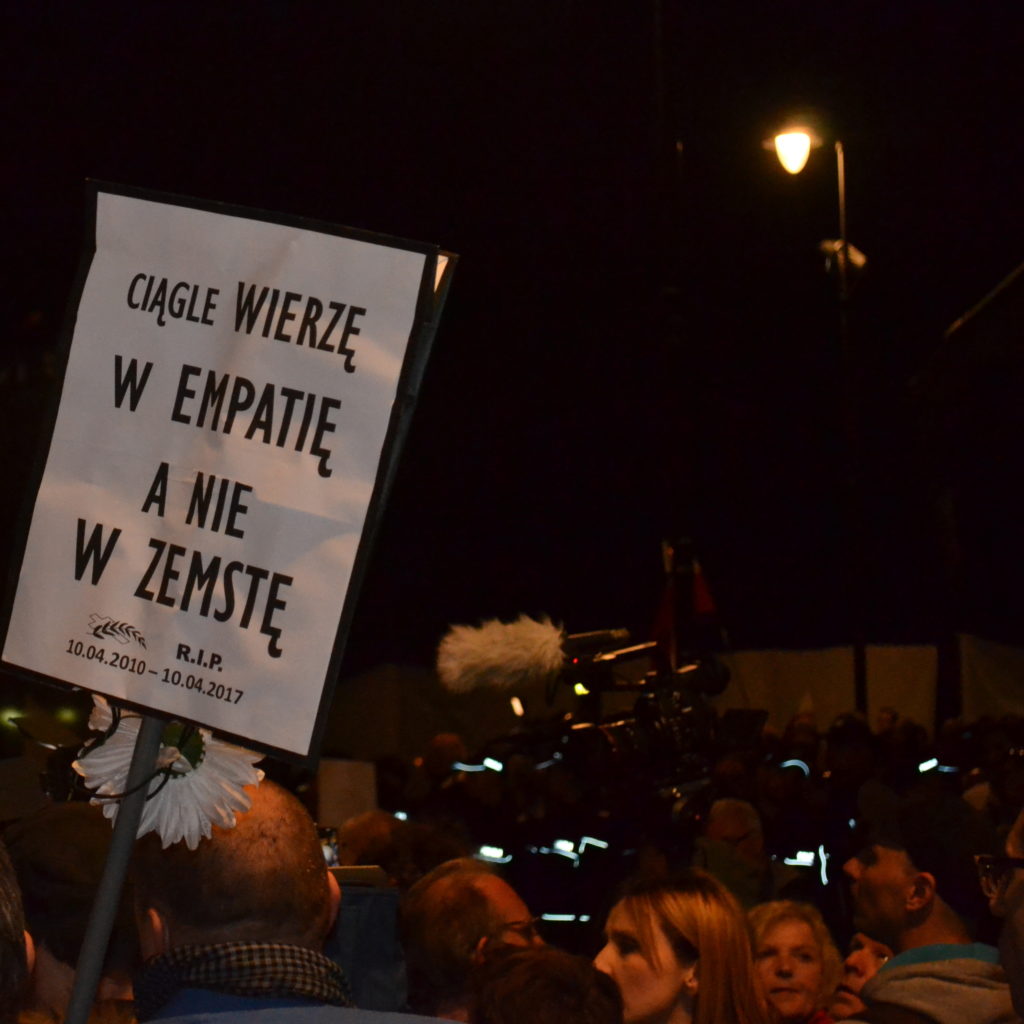

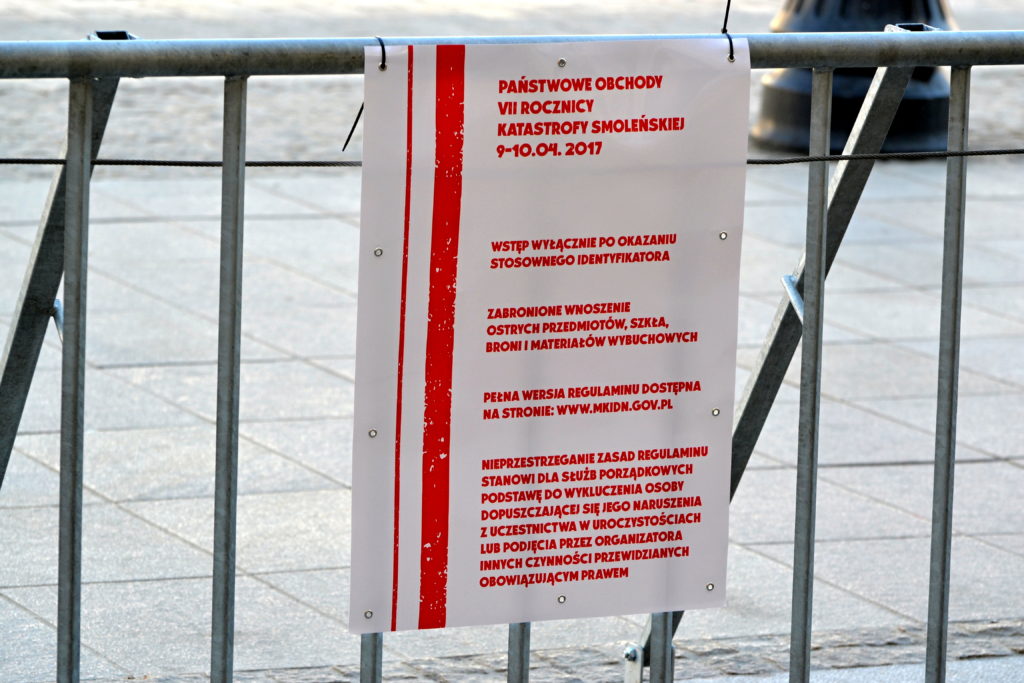

The crowd at Piłsudski Square was organized by a group called “Obywatele RP” (Citizens of the Polish Republic). This is not affiliated with the better known and much larger Committee for the Defense of Democracy [KOD], though the two groups share the same basic goals. The difference is that ORP engages in peaceful civil disobedience with the goal of exposing the regime’s brutality.

The crowd at Piłsudski Square was organized by a group called “Obywatele RP” (Citizens of the Polish Republic). This is not affiliated with the better known and much larger Committee for the Defense of Democracy [KOD], though the two groups share the same basic goals. The difference is that ORP engages in peaceful civil disobedience with the goal of exposing the regime’s brutality.