Is Democracy Doomed in Poland?

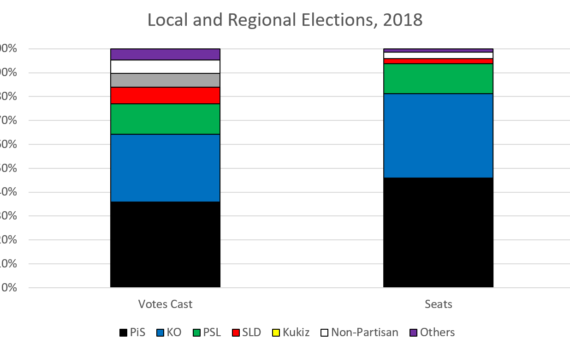

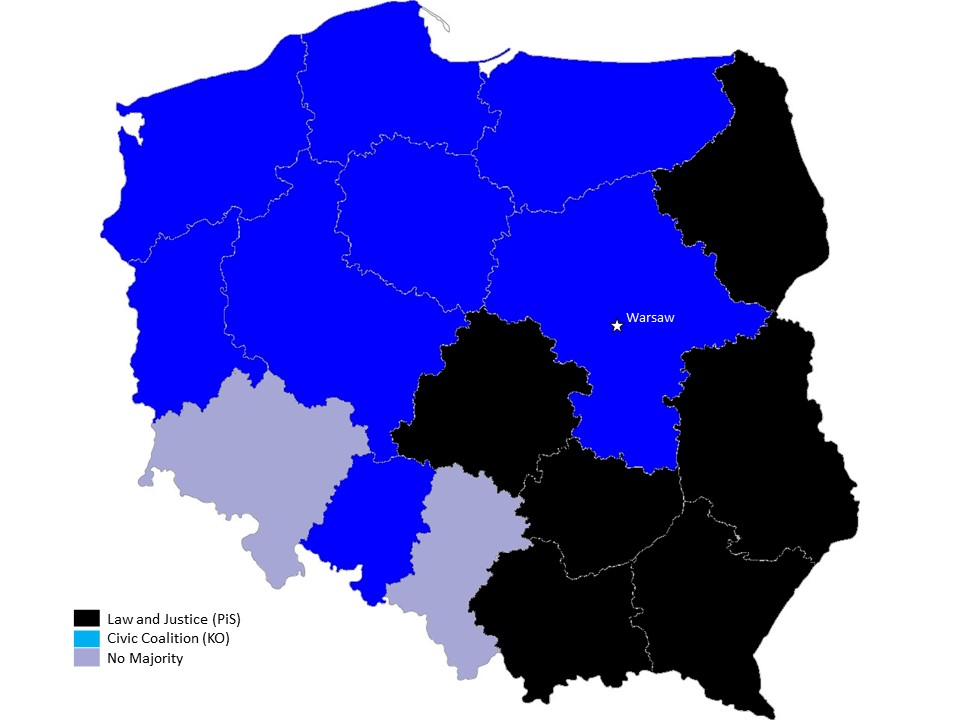

In the aftermath of last week’s EU elections in Poland, there has been an abundance of lamentation and jeremiads by commentators on the left and center-left. Jarosław Kaczyński’s Law and Justice Party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, or PiS) achieved its greatest electoral success ever, both in absolute and relative terms. Last Fall, during local and regional elections, there were signs that the opposition had won enough support in Poland’s towns and cities to make victory in the next parliamentary elections plausible. Now that objective seems further away than ever.

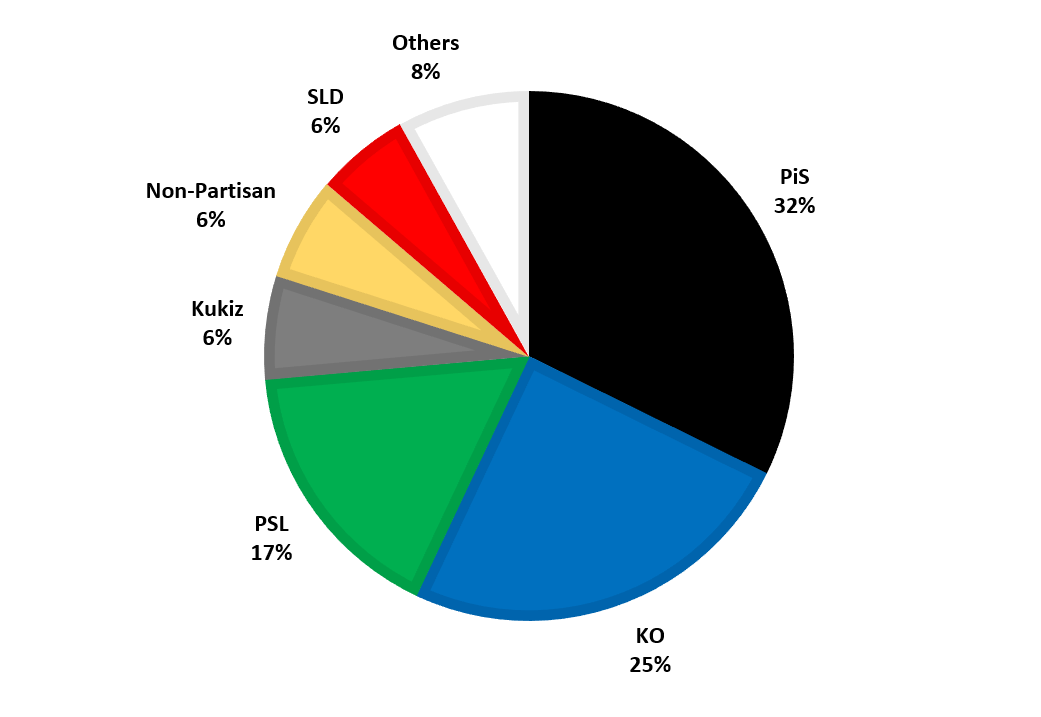

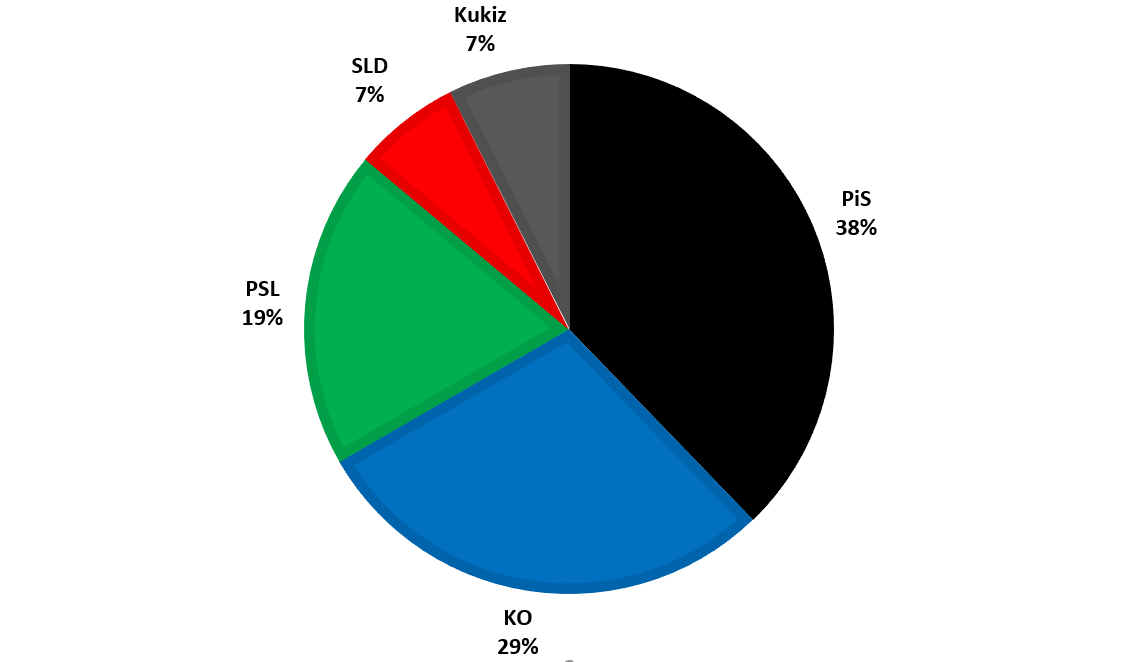

Matters seemed to get even worse this past weekend, as news emerged that the Polish Peasant’s Party [Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe, or PSL] was considering a break from the anti-PiS, pro-democracy European Coalition [Koalicja Europejska, or KE]. For quite some time, supporters of liberal democracy have hoped for the creation of a broad front of allied parties from the center left and the center right, on the assumption that PiS could only be defeated if everyone joined together and put aside the issues that would otherwise divide them. After all, there is little sense squabbling about this or that budget priority, or this or that economic plan, when the very foundation of liberal democracy is at stake. Well, that coalition was finally created, including the PSL, the center-right Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska, or PO), the liberal Modern Party (Nowoczesna), the social democratic Alliance of the Democratic Left (Sojusz Lewicy Demokratycznej, or SLD), and the Greens (Zieloni). Only the anti-clerical, left-liberal Spring Party (Wiosna) and the far-left Together Party (Razem) ran on their own. For their part, PiS had subsumed nearly the entire nationalist right, except for a small group that we might call the counter-cultural right (Kukiz 15) and an alliance of antisemitic even-further-right fringe parties calling itself The Confederation (Konfederacja). The results were unambiguously a disaster for the center and the left, even if we bring together all the various parties on the PiS and anti-PiS divide. The gap of slightly over one million votes is huge, considering that parliamentary elections tend to bring out 15-16 million voters (out of about 30 million eligible voters).

But let’s not be too hasty to predict a PiS victory in the next elections, which must take place this coming Fall. This balance of power, if it were to carry forward, would not necessarily lead to a significant PiS majority in the next Sejm (the Polish parliament). Polish electoral law requires a party to get at least 5% of the vote, which would cause Konfederacja, Kukiz 15, and Razem to fall by the wayside. The remaining balance would be a Sejm with 232 seats for PiS, and 228 for the opposition (197 for KE, and 31 for Wiosna). That’s an even smaller majority for PiS than they currently enjoy (238 votes), and they would no longer have the cushion of the 26 seats currently held by Kukiz 15, nor the 20 seats occupied by right wing politicians who declared their partisan independence since the last elections. Put differently, if last week’s vote were repeated in the Fall, PiS would be a mere 115,000 votes away from losing power to a coalition of KE and Wiosna.

Polish politics has always been characterized by “wasted” votes—that is, ballots cast for parties that didn’t make it past the 5% bar. Typically these don’t shift the overall balance of power, because there are fringe parties scattered across the political spectrum. But twice in the history of the Third Republic there have been spikes of significant “wastage,” leading to major distortions: in 1993, when the law was first instituted and the right was almost locked out of the Sejm because it hadn’t yet coalesced into a single movement; and then again in 2015, when PiS benefited from that very system. If the results this coming Fall are close to what they were last week, it is very possible that the shoe will again be on the other foot.

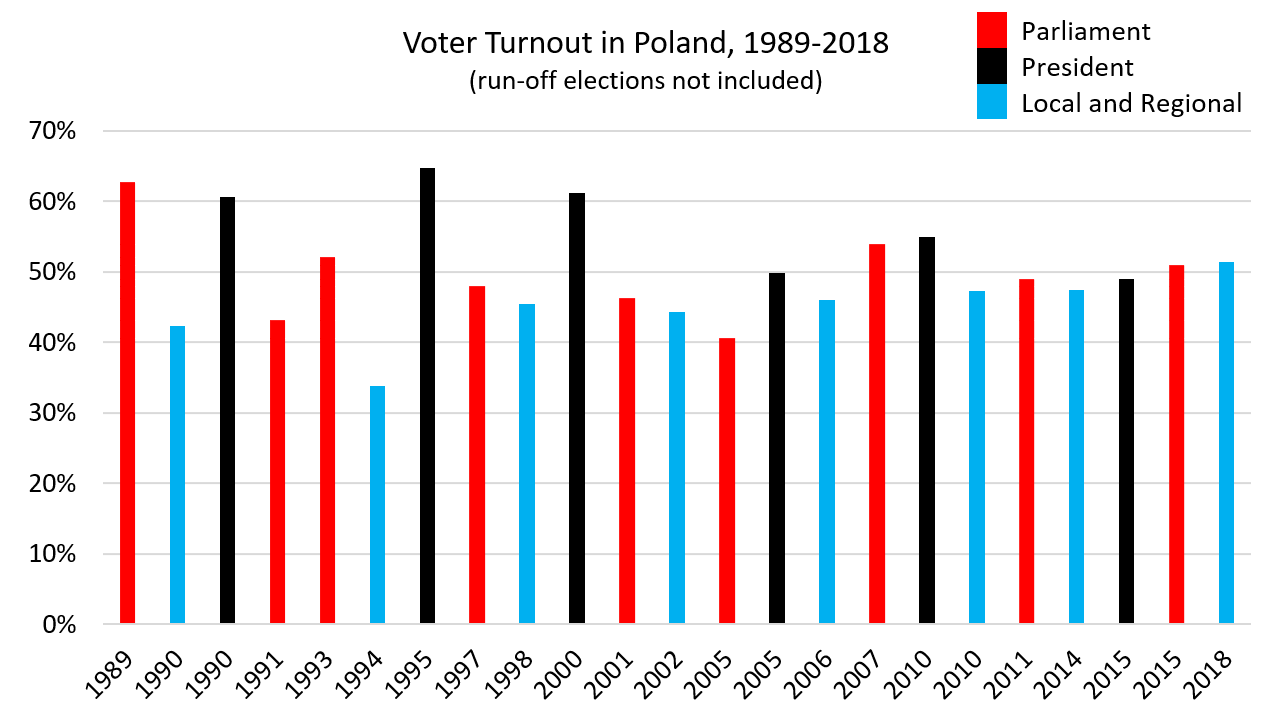

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there is no reason to believe that the vote in the Fall will be a replication of what happened last week. Historically, votes to the EU parliament have been poor predictors of national elections. In this specific case, the dynamic could be altered significantly if PSL does indeed decide to break from the coalition. I might have to acknowledge that my own hopes for a unified opposition were mistaken, because the increase in votes that PiS got in the last election came almost entirely from areas that had once been the strongholds of PSL. That party is unique in modern Polish politics. It is the only currently active party that has a continuous existence from before WWI until the present day, and its ideological identity has been somewhat fluid over that long history. In both the Second and Third Republics, the PSL has served in governing coalitions with both left and right wing parties, and precisely because of their flexibility they have come to specialize in a distinctive form of clientelistic politics. This has made it impossible to expand beyond a narrow base in a few rural areas, but it has also allowed the party to consistently remain above (sometimes barely) the 5% cutoff. It seems that the party’s constituents were willing to accept government coalitions with various larger parties, regardless of ideological profile, because that allowed the PSL leadership to retain control over government offices that could be used to sustain patronage networks. But merging into a coalition before an election meant that the PSL name was not on the ballot, and that the rural voters who would usually vote for the party had to choose between KE (a bloc dominated by urban liberals and leftists) or PiS. Not surprisingly—in hindsight—they went for the latter or just stayed home. This alone could account for most of the increase in the size of the PiS electorate. Significantly, PiS did not gain new voters in any of the districts known for more intense nationalism or religiosity; instead, their gains were in rural areas in the north and west of the country that had up till now demonstrated a somewhat more centrist (perhaps coldly pragmatic) profile. In other words, these are not areas that are ideologically aligned with PiS, but rural areas that can be swayed to vote for Kaczyński’s party if the economy seems strong (which it does) and if all the other options are linked to the cosmopolitan sensibilities of Poland’s liberal elite. Meanwhile, the remaining parties within KE will not have to worry about the concerns of the PSL, allowing them to offer a clearer message that aligns with the priorities of their urban, liberal base. That, in turn, could help them generate some more excitement and spur higher turnout.

But big questions remain. If PSL does run on its own, will their voters switch back in the Fall, or will they feel betrayed by their old political patrons and instead stick with PiS? Kaczyński will doubtlessly work hard over the coming months to demonstrate his party’s largesse to precisely these swing districts. Even if these voters do return to the PSL, will it be enough to keep the party about the 5% level? If not, that will just draw votes away from the anti-PiS opposition. Finally, what will happen to the other three small parties that either just missed or just passed the 5% line: Konfederacja, Kukiz 15, and Wiosna? In all three cases, a tiny shift in the vote totals one way or the other could make an enormous difference, and completely change the balance of power.

The bottom line is that the results of the parliamentary elections are by no means a foregone conclusion. Surveys have shown that among the overall population, the divide between pro-PiS and anti-PiS is well within the margin of error. No matter what happens, there won’t be an overwhelming mandate in either direction (despite the claims that the winner is sure to make). Given this context, everything will depend on the complex and tedious details of partisan maneuvering and campaign strategy. That’s the kind of politicking that rarely inspires enthusiasm, but at stake this year could be the future of liberal democracy in Poland.