Kaczyński is not Poland

Democracy is a great principle for governing a country, but a lousy tool for understanding one.

Consider this syllogism:

- The Poles selected a new parliament through a free and fair election

- A majority of the new parliamentarians are from PiS (the Law and Justice Party)

- PiS was therefore able to form a government through legitimate, constitutional means

- PiS has now provoked a constitutional crisis by ignoring the constraints of parliamentary democracy

- Therefore, the Poles have abandoned their faith in parliamentary democracy.

If we read accounts of recent events in Poland in the international press (particularly from Western Europe), we frequently encounter a form of this argument. “The Poles” have given up on democracy; “the Poles” are turning away from European values; “the Poles” are returning to familiar patterns of xenophobia, authoritarianism, and “backwardness.” Let’s set aside for a moment the lamentable pattern of orientalist stereotyping, and overlook the hypocrisy of any implication that Poland is in some way different from Western Europe or the US (need I even mention Marine Le Pen or Donald Trump?). My point today is different: regardless of the results of the October election, the current government’s unconstitutional and antidemocratic power grab reflects the preferences of a small minority of the Polish population.

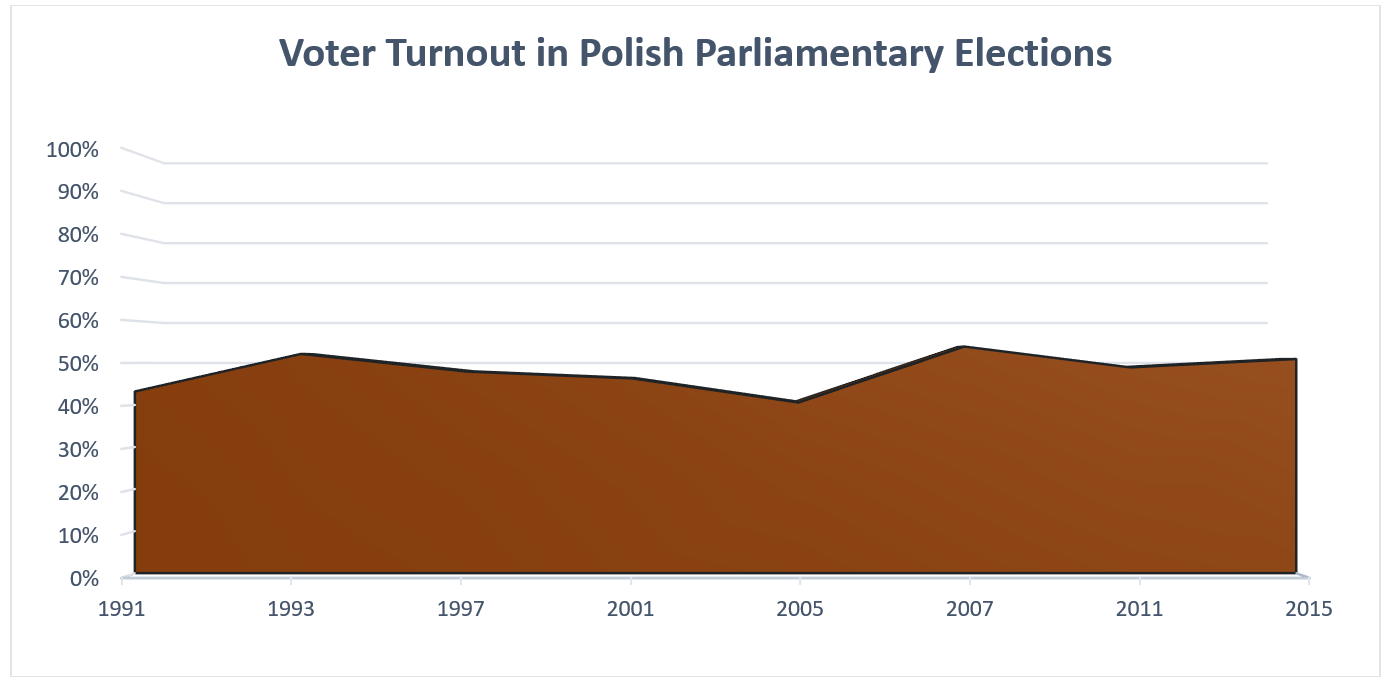

Small changes in electoral results can have huge consequences, and that makes it easy to overestimate actual shifts in popular attitudes, values, and norms. On October 25, just under 51% of the Polish electorate voted, which is actually a percentage point better than last time (2011). This is typical: the turnout over the past 25 years has always been poor, never going much past 53%

Out of the 38.5 million Poles, 30.6 million are eligible to vote, but it seems safe to say that the politically engaged population consists of around 15 million people. Of these, 5.7 million voted for PiS last October, compared to 4.2 in 2011. If we group together all the right-wing parties that oppose liberal democracy, we get about 7.8 million in 2015 and 7.3 million in 2011.

Bottom line: the political earthquake that gave PiS the largest parliamentary majority in Polish history (yes, even if we go way back to the interwar years) was caused by a shift in about 3% of the population (if we just count the PiS votes) or about 1% of the population (if we count all the votes going to the various parties of the far right).

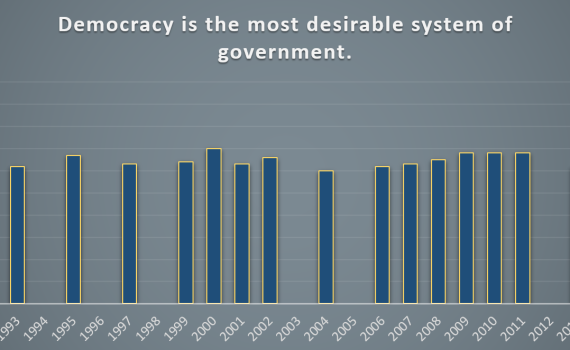

Poland has not really changed, even though Polish politics has been frighteningly transformed. In 1992, 52% of Poles surveyed by CBOS agreed that democracy was superior to all other forms of governance; today 64% feel that way. Although CBOS does not report the margin of error for their surveys—which is inexcusable, but that’s another matter—I suspect that much of the fluctuation in this statistic over the years would be accounted for by statistical noise.

All this makes the events of the past month even more unsettling. Currently a majority of Poles feel that their democracy is threatened, and I share their concerns. The president and the prime minister, acting under the direction of their behind-the-scenes leader, Jarosław Kaczyński, have refused to acknowledge the rulings of the Constitutional Tribunal, Poland’s supreme court. I took some comfort after the elections when PiS fell short of the 2/3 majority needed to revise the constitution, but I now see that I was naïve: Kaczyński intends to simply ignore the constitution and proceed with his plan to transform the Polish political system.

In 1832, US President Andrew Jackson is reported (perhaps apocryphally) to have responded to a supreme court ruling against his administration by declaring, “the court has made its decision; now let them enforce it.” This episode is presented to Americans today as a dangerous challenge to our constitutional order, and the fact that the judicial branch recovered from that moment is held up as a testament to the strength of our system. That story gives some reason for hope, because it reminds us that liberal democracies can survive even a concerted populist attacks. But frankly, that hope weakens when set alongside the many counterexamples of countries that have recently failed to withstand attempts by the far right to seize total power. With Orbán, Putin, Erdoğan, and others blazing the trail, Kaczyński’s political project appears all too realistic.

A sturdier hope comes from the bird’s-eye-view of the Polish population that I’ve offered here. PiS might succeed in dismantling multiparty democracy, and they are certain to do a lot of damage to Poland even if they ultimately fail (and I continue to believe that they will fail). But Poles today are still the same people who have achieved such stunning success over the past few decades, with roughly the same values and norms. Kaczyński must resort to such heavy-handed, anti-democratic methods precisely because he does not embody the will of the Polish people, if we take that phrase to refer to a hegemonic worldview shared by all or nearly all Poles. A few years ago most observers were writing him off as a failed fringe politician, and his rapid return to power has shown us how seriously we underestimated him. But support for his nationalistic project is roughly the same today as it has always been: marginal and extreme.