Civic Strike

Today, on the anniversary of the declaration of Martial Law in 1981, protests (labeled a “Civic Strike”) are being held all over Poland. The organizers issued a statement that I’ve translated below (the original is here). Following it is an excerpt from an interview given in response to this statement by Jarosław Kaczyński. Finally, I’ve translated the list of demands compiled by the organizers of today’s protests.

Here in Warsaw the demonstration will begin in under three hours. Check back later for my impressions from the event.

__________________________

Stop the devastation of Poland!

Almost exactly one year ago, on December 12, we protested for the first time against the paralyzing of the work of the Constitutional Tribunal and the violation of the Constitution by the government and the President.

Today we know that a year of the Law and Justice government has been, above all, time for the methodical destruction of Poland, its relations with its neighbors, and its image in the world. It has been a time for subordinating to partisan interests nearly every public institution: judges, prosecutors, civil servants, and the army. The authorities have taken over the public media and transformed it into a pro-government organ, which does not hesitate to lie and manipulate. PiS wants to make it more difficult for us to gather and protest

Today Polish society is, as never before, deeply divided. We feel above all anger at the actions of the government, the parliamentary majority, and the President. The authorities have methodically destroyed that which we managed to build over the previous decades. It is also destroying us as a society—setting us against each other, trying to divide and conquer.

Destructive laws prepared without any consultation and passed in haste have only one goal: to increase the power of PiS at the cost of civic liberty. The PiS government is systematically ruining Polish culture, hampering economic development, carrying out an assault on women’s rights, and now preparing the imposition of reforms that would create massive chaos in Polish schools.

Therefore we call upon everyone—men and women, teachers, parents, health-care workers, miners, farmers, business people, artists, journalists, judges, prosecutors, police officers, soldiers, and also NGOs, political parties, local self-government, unions—to join together in opposition to all this.

Today the moment has arrived to renounce obedience to these authorities. [Dziś nadeszła chwila, by wypowiedzieć posłuszeństwo tej władzy].

On the 13th of December we will take to the streets of all Polish cities and towns, and show that we do not accept the destruction of Poland. We will protest against the arrogant autocracy of PiS. But we will also show that we can stand together. And we will not (as on December 13, 1981) allow ourselves to be set against each other, we will not allow any confrontations.

We will not surrender our liberty. We will not surrender our culture, education women’s rights, labor laws, self-government, NGSs, media, farms.

Enough discrediting of Poland on the international stage! Enough cracking down on liberty and democracy! Enough of this madness!

- Sławomir Broniarz

- Władysław Frasyniuk

- Krystyna Janda

- Jacek Jaśkowiak, Prezydent Miasta Poznania

- Jacek Karnowski, Prezydent Miasta Sopotu

- Mateusz Kijowski

- Marta Lempart, inicjatorka Ogólnopolskiego Strajku Kobiet

- Płk dypl. rez. mgr inż. Adam Mazguła, były dowódca wojskowy, harcmistrz

- Ryszard Petru, Przewodniczący Nowoczesnej

- Krzysztof Pieczyński, aktor, stowarzyszenie Polska Laicka

- Grzegorz Schetyna, Przewodniczący Platformy Obywatelskiej

- Aleksander Smolar, Prezes Fundacji im. Stefana Batorego

- Lech Wałęsa

____________________________

Reacting to this statement, Jaroslaw Kaczynski said “This is an appeal of an anti-state character, and basically we are dealing here with a crime. This is an appeal to commit a crime…For our part, there will certainly be efforts to bring some order to the activities of the opposition, though again I fear that this will be treated as…an attempt to limit democracy.…Nonetheless, we will put forward such proposals soon. And they will be proposals aimed at ensuring that the political conflicts natural in a democracy are conducted as they ought to be conducted, not as they are at the present moment.”

_____________________________

A more detailed lists of demands by the organizers of today’s protests can be found here. They are as follows:

- The resignation of the government of Beata Szydło

- The cessation of activities aimed at constraining the functioning of state institutions, particularly activities paralyzing the functioning of the Constitutional Tribunal and the general courts

- The cessation of activities weakening women’s rights and suppressing the Convention Against Domestic Violence

- The withdrawal by the government of the harmful and ill-prepared education reforms

- The upholding of the constitutional principle of the separation of Church and State

- The hiring of people for administrative positions based on qualifications and experience, not party loyalty.

- The consistent repudiation of all manifestations of fascism, nationalism, and xenophobia

- The political independence of cultural institutions and the public media

- The preservation of complete freedom of assembly

- The preservation of the autonomy of NGOs

- The return of full property rights, particular regarding rural land (that is, an end to the threat of nationalization) as well as an increase of the limit on tax-free earnings for everyone

- The cessation by the government of the exhumation of the victims of the Smolensk catastrophe whenever so requested by their relatives

- The cessation of the formation of the Army of Territorial Defense in its current form—that is, with the possibility that it might be used against citizens of the Polish Republic.

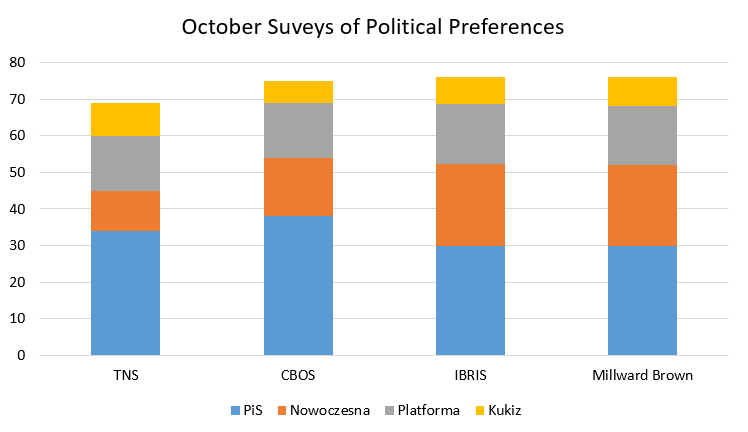

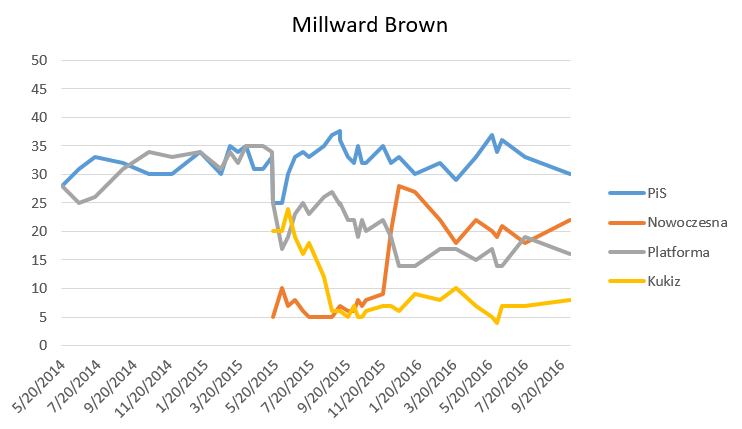

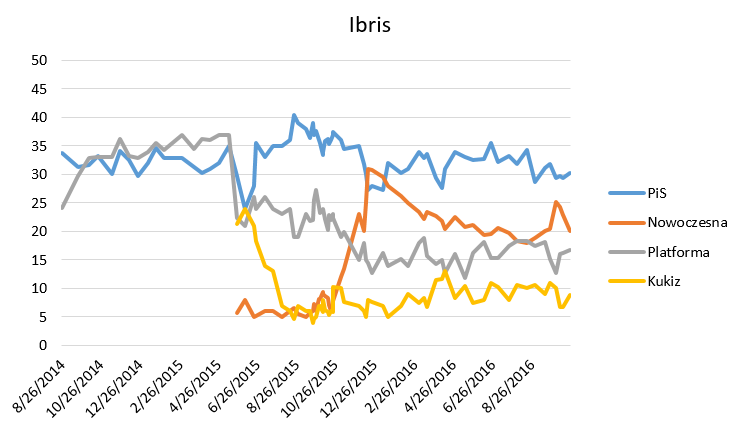

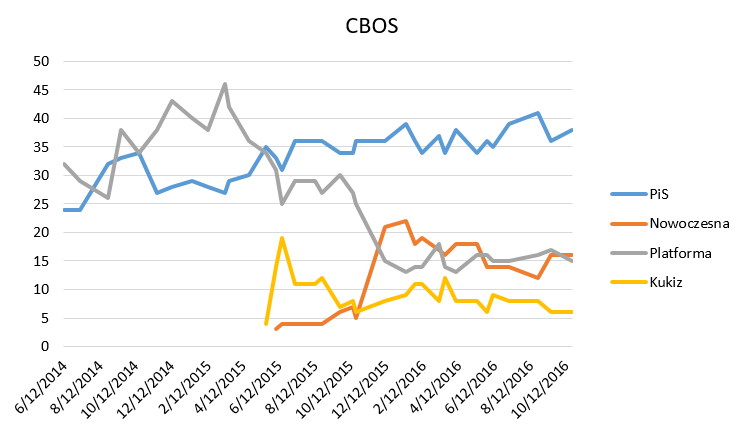

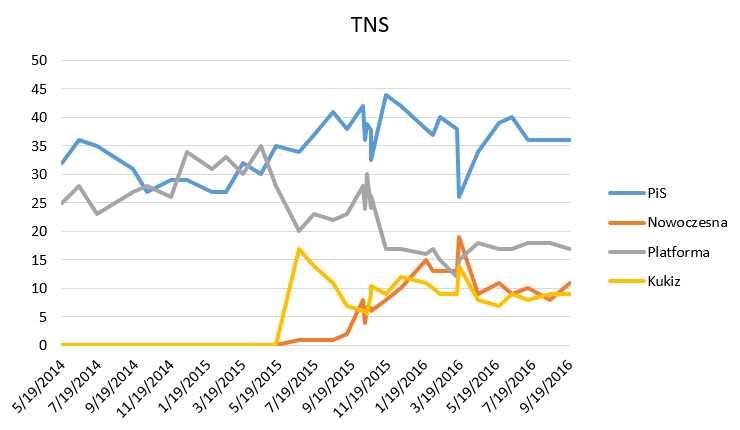

Moreover, the two firms that are most generous to PiS are CBOS (which is a state-owned firm) and TNS (which provides polling data to the state-run television news program). Meanwhile, Ibris and Millward Brown collect data for media outlets in opposition to PiS. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that somewhere, numbers are being massaged with a specific outcome in mind, but there is no actual evidence for that. If anyone knows more about the specific methodological decisions that have generated these differences, please let me know.

Moreover, the two firms that are most generous to PiS are CBOS (which is a state-owned firm) and TNS (which provides polling data to the state-run television news program). Meanwhile, Ibris and Millward Brown collect data for media outlets in opposition to PiS. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that somewhere, numbers are being massaged with a specific outcome in mind, but there is no actual evidence for that. If anyone knows more about the specific methodological decisions that have generated these differences, please let me know.