My Facts are Better than Your Facts

One of the most frustrating aspects of political life today is that we mostly argue about the basic facts, making it impossible to even discuss competing values, goals, preferences, and interests. This is just as true in Poland as it is in the United States.

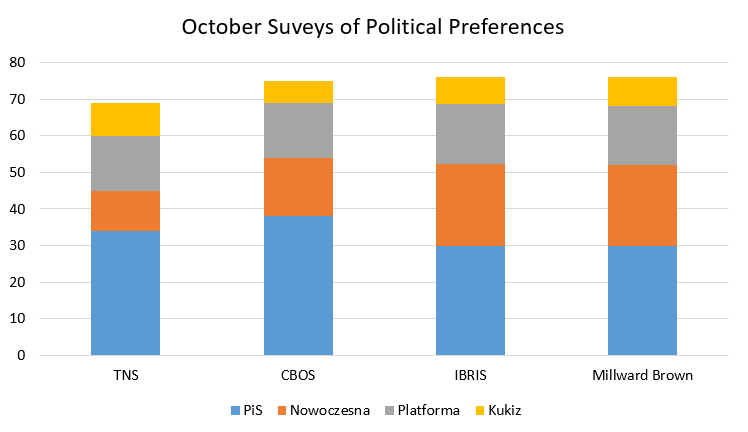

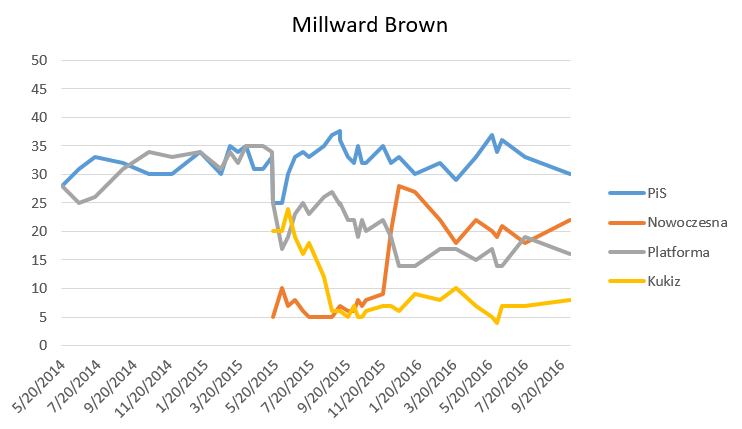

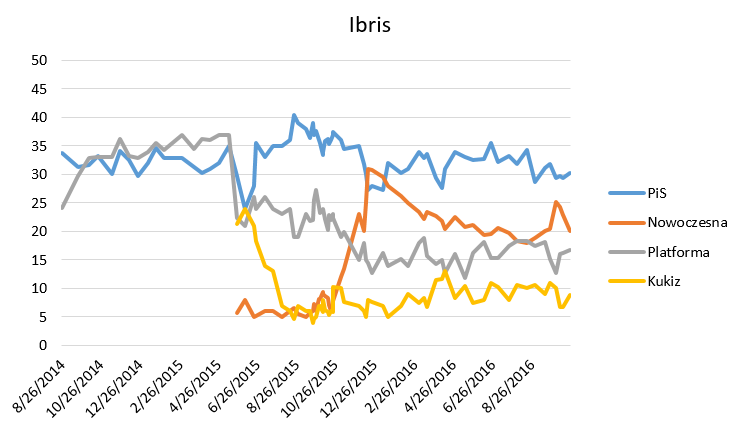

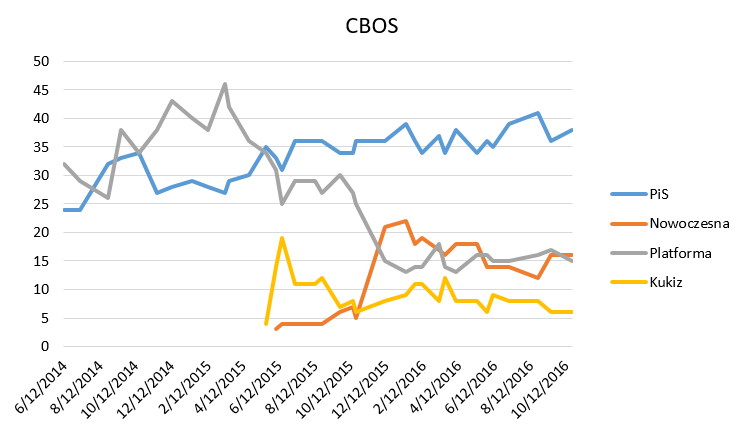

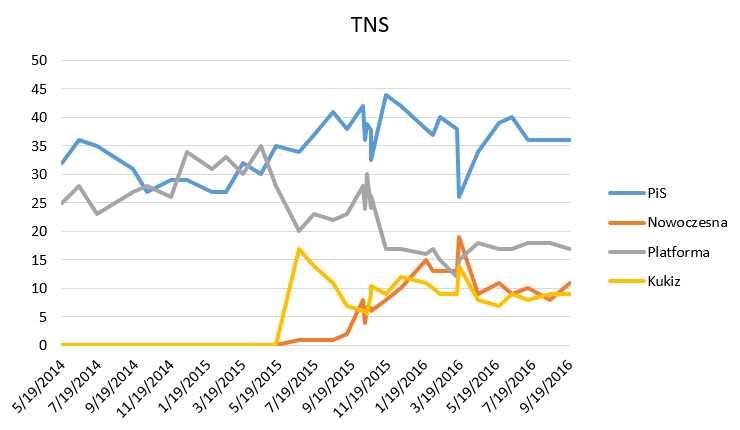

There are many obvious and extreme examples of this, but I want to mention one that is much more subtle (but no less dangerous for that). Last week I discussed some of the trends in party preferences, noting the beginnings of a decline for PiS. A few new surveys have come out over the last few days, and when reviewing those I noticed that the (unavoidable) differences between competing polling firms had grown startlingly large. Depending on your preferred source, PiS currently has either 30% or 38% support, and Nowoczesna has either 11% or 22% support.

I recognize, of course, that each firm employs alternative methods for collecting, sampling, and weighting their results, so some divergence is inevitable. But looking back, we see that these patterns have been quite consistent.

Moreover, the two firms that are most generous to PiS are CBOS (which is a state-owned firm) and TNS (which provides polling data to the state-run television news program). Meanwhile, Ibris and Millward Brown collect data for media outlets in opposition to PiS. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that somewhere, numbers are being massaged with a specific outcome in mind, but there is no actual evidence for that. If anyone knows more about the specific methodological decisions that have generated these differences, please let me know.

Moreover, the two firms that are most generous to PiS are CBOS (which is a state-owned firm) and TNS (which provides polling data to the state-run television news program). Meanwhile, Ibris and Millward Brown collect data for media outlets in opposition to PiS. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that somewhere, numbers are being massaged with a specific outcome in mind, but there is no actual evidence for that. If anyone knows more about the specific methodological decisions that have generated these differences, please let me know.

It might seem trivial to quibble over a few points in an opinion survey, but in fact these subtle differences can have an even greater impact than more obvious lies. Depending on your source, you could spin either the headline “PiS support falls below 30%” or “PiS support approaches 40%.” That takes us from the world of arguing over statistical methods towards completely different realities. On one side, the PiS regime is beginning to crumble, thanks to mass protests and EU pressure. On the other side, PiS’s assertive foreign policy and generous social programs are convincing more and more Poles to accept Kaczyński’s leadership. Since few people understand the nuances of polling methodology or statistical interpretation, most of us accept whichever result feels intuitively right to us. Or even worse, we throw up our hands and assume what all the polling is being manipulated, so we shouldn’t trust any of it. I say that this is worse, because at the root of the rise of the radical populist right (Trump, Le Pen, Kaczyński, Orbán, Putin, Modi, Erdogan, etc.) is a loss of faith in public institutions of all varieties.

A certain skepticism towards those in positions of power is vital to a healthy democracy, but when that tilts over to a nihilistic rejection of all expertise, all reasoned arguments, all evidence, then we are on very thin ice. We academics have spent the last few decades promoting the idea that knowledge is always political, and we’ve delighted in debunking the unrecognized assumptions of Enlightenment rationality. I’ve done some of this critical deconstruction myself, and I remain proud of that work. Those opposed to these scholarly trends have accused us of promoting absolute relativism, but that has (usually) been a straw-man argument. I won’t speak for other disciplines, but we historians are too grounded in the habits of using archival evidence to succumb to the more extreme claims of postmodernism. I see these methodological and theoretical innovations, at least within the discipline of history, as undeniably positive. But we have not done as well communicating to our students and to the broader public the difference between healthy debunking and deconstruction on the one hand, and the dangerous nihilism that dissolves the very concept of expertise on the other. We therefore deserve at least a little bit of the blame when people respond to misinformation with a cynical shrug rather than with outrage.

But of course I would say that, wouldn’t I?