It Could be Worse

In Dicken’s A Christmas Carol, the “Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come” offers Scrooge a horrifying prophesy of his future. English literature’s most famous libertarian then falls to the ground and begs, “Assure me that I yet may change these shadows you have shown me, by an altered life!”

I recently spent several weeks in Hungary. Now that I’m back in Poland, I feel that I’ve awakened from a similar vision of a potential future. Warsaw has not—yet—been transformed into a “Budapest on the Vistula,” but that is precisely the goal that Lech Kaczyński has long advocated. I can understand why: Hungary has become an exemplary “antiliberal state” (as their president, Viktor Orbán, calls it). In an infamous 2014 speech, he said that “liberal democratic states can’t remain globally competitive.” To defend this point, he referred to the supposedly “successful” examples of Russia, Turkey, and China, noting that “none of them are liberal, and some of them aren’t even democracies.” Orbán’s Hungary is indeed a paradise for those in Poland who oppose liberal ideals like pluralism, the rule of law, separation of powers, an independent media, a nonpartisan civil service, academic freedom, and the separation of church and state.

Unlike Scrooge, it isn’t in my power to avert Poland’s Christmas Yet to Come. Some would say that it isn’t even my concern, since I’m not a Polish citizen—though I do feel a strong enough bond to this country to care.

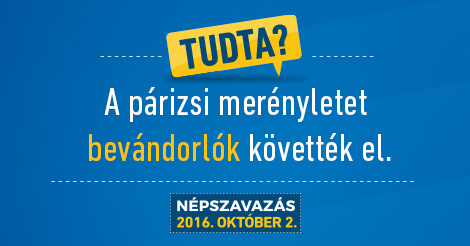

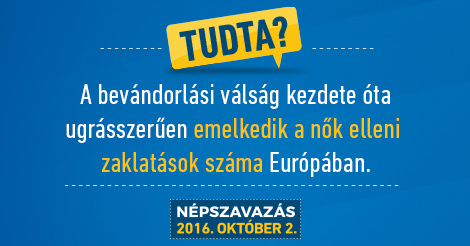

One example perfectly summarizes how bad things have become in Hungary. In early August, the government began blanketing the country with a propaganda campaign entitled “Tudta?” [Did you know?]. In subway stations and bus stops, on billboards, throughout the media: you can’t avoid the ubiquitous blue posters offering “information” about Muslim refugees in Europe (always labeled “immigrants”). All this is leading up to a referendum scheduled for October 2, which will ask Hungarians (with wording the government considers perfectly neutral and reasonable), “Do you want the European Union to be able to mandate the obligatory resettlement of non-Hungarian citizens into Hungary even without the approval of the National Assembly?” Theoretically, Hungarian law (insofar as that phrase has not become an oxymoron) specifies that campaigning for the referendum cannot begin until 50 days prior to the vote, but the government has evaded this by claiming that it is just providing “public service messages” for informational purposes.

What sort of “information” are the posters conveying? Some of the examples include:

- “Did you know that the Paris bombings were committed by immigrants?”

- “Did you know that since the immigration crisis began, the harassment of women in Europe has increased by leaps and bounds?”

- “Did you know that nearly a million immigrants from Libya are coming to Europe?”

- “Did you know that since the immigration crisis began, more than 300 people have died in terrorist attacks in Europe?”

- “Did you know that Brussels wants to settle a whole city’s worth of illegal immigrants in Hungary?”

I guess the Hungarian definition of “city” is quite broad, because the actual number of refugees allocated to Hungary by a proposed EU agreement is a whopping 1,294. Given this, the €16,000,000 propaganda campaign would amount to €12,000 per asylum seeker, had the money been spent on refugee services rather than hate speech.

The depiction of Muslim refugees as utterly alien and evil has become central to Orbán’s ideology. Authoritarian regimes require an enemy, and he has found one. Sadly, it is working: surveys show that over 70% of Hungarians will vote “no” in the October referendum, and insofar as the government is losing any support, it is to the even more extreme far-right Jobbik party. If there is any consolation here at all, it is that vanishingly few Muslims actually live in Hungary, so this campaign of hatred will not lead directly to much physical violence in the short term. But it won’t be hard to redirect these emotions towards other “enemies,” such as liberals, gays, Roma, or anyone else who cannot fit within Orbán’s definition of a true patriot.

One can certainly find similar hate-speech in Poland, but the situation is not nearly as dire—yet. While the state-backed public media spouts PiS propaganda, the viewership of those stations is plummeting. A vigorous independent media remains, both in print and (more importantly) on TV and radio. Ratings for the government’s channels have fallen behind both of the leading independent channels, and the once dominant news service of the public media has fallen into third place. Orbán’s overwhelming popularity cannot even be approached by Kaczyński, who has the highest negative ratings of any Polish politician (he is distrusted by 53% of the population). If elections were held today, PiS would win just over a third of the votes (though they would probably remain in power thanks to the fragmented, hapless opposition). Even the anti-immigrant message can’t work quite as well here, because ironically, the (otherwise strongly pro-PiS) Catholic Church is slightly constrained in its rhetoric by Pope Francis’ forceful support of Christian charity. In other words, pluralism remains strong in Polish society, even if the reins of power are held entirely by Kaczyński.

A year ago I would have stopped there, with a note of confidence and optimism. That’s no longer possible, because the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come cannot be ignored. But like Scrooge, I insist on believing that a change of course is always possible.