Poles Want Democracy

Do Poles value democracy? That’s a silly question: obviously it depends on what you mean by “democracy.” Nowadays authoritarian leaders like to describe their regimes as “anti-liberal democracies,” and very few public figures openly criticize democracy as such. When Jarosław Kaczyński, Victor Orbán, Marine Le Pen, or Donald Trump proclaim their belief in democracy, they mean that everyone should obey the proclamations of governments that truly represent the interests of the nation. To go against the (singular) will of the people is to defy democracy, in this vision. Liberals, on the other hand, insist that democracy should be characterized by an ongoing respect for compromise, consensus, and respect for minority opinions (and identities). In this second worldview, firm legal and institutional frameworks and a strong sense of political norms should constrain the power of the majority from doing anything too extreme. Interestingly, for much of the 19th century, Europeans didn’t usually call that worldview “democracy,” but rather, “representative government.” John Stuart Mill famously argued that the latter was preferable over the former, precisely because “the tyranny of the majority” (as he put it) posed a threat to individual liberty. Against Mill’s arguments were “democrats” who hearkened back to Rousseau’s idea of the “popular will.”

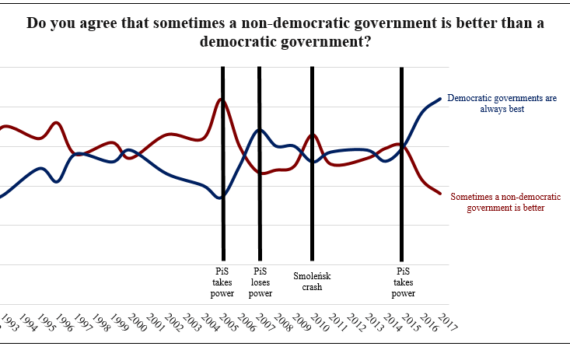

For better or worse, we don’t have that distinction any more: everyone nowadays is supposed to believe in democracy, with adjectives attached when we want to clarify what sort of democracy we like. At least, that’s the impression one would get listening to the political debates of the early 21st century: you accuse your opponents of being antidemocratic, but never claim that label for yourself. Yet an interesting survey has been conducted in Poland ever since the fall of communism, asking people “Do you agree that sometimes a non-democratic government is better than a democratic government?” The newest iteration of this poll shows that a record-high number of people believe that democracy is always the best, though a significant 28% continue to envision circumstances when it would be better to dispense with democratic principles.

There are many possible interpretations of this result, and they depend on a more nuanced exploration of how the meaning of the term “democracy” has shifted in public discourse over the past 20 years. For example, it is possible that there is a stable level of support for the idea that a strong leader elected by a majority should have absolute power. In that case, the recent drop in people who question the value of democracy would be tied to the spread of the concept “anti-liberal democracy.” A lot more research would be needed to verify or debunk that hypothesis.

But for all the ambiguity of this survey, a very curious pattern is evident. When PiS first rose to power in 2005, the number of people doubting the value of democracy was at an all-time high. During the ensuing two years, appreciation for democracy rose dramatically, peaking at the moment when Jarosław Kaczyński lost power in 2007. Similarly, after the party’s return to power in 2015, appreciation for democracy once again jumped upwards. It is tempting to conclude that the experience of authoritarian one-party rule makes people appreciate the inefficiencies, the tedium, and the unsatisfying compromises of liberal democracy. That’s what I want to believe—though it could also be true that authoritarian populists express opposition to democracy whenever they are out of power, but like it when they are in charge. But I’m going to reject that possibility for now, because it is so much more hopeful to believe that Poles are rallying around democracy now that they feel its absence. If that is true, then it suggests that opposition to authoritarianism is growing.

I have no good reason to believe that this is the case, but I’m determined to find some rays of hope during these dark times.