Our Perpetrators, Our Victims

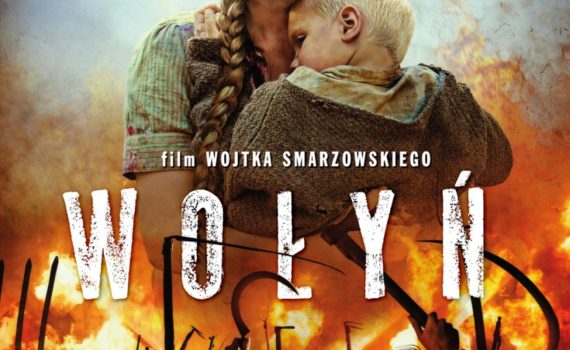

Two controversial movies have been released in Poland in recent weeks. The first, which I’ve already written about on this blog, is Antoni Krauze’s Smoleńsk, a tendentious regurgitation of the conspiracy theories surrounding the 2010 crash that killed an airplane full of Polish dignitaries, including President Lech Kaczyński. The second was Wojciech Smarzowski’s Wołyń, a powerful retelling of the infamous Volyhnia massacre during WWII, in which tens of thousands of Poles were killed by Ukrainian nationalists. Artistically, these two have little in common. The former is laughably bad, with a 2.9 rating on filmweb.pl, whereas the latter is already accumulating awards and enjoys a score of 8.4. Thematically, they seem at first glance to be equally divergent: both deal with death, but one explores a tragic accident (which it tries to embed with mythic importance through fantasies about nefarious plots), whereas the other relates a complex tale of war, ideological perversity, nationalism, human debasement, and heroism. Krauze’s film will be soon forgotten, whereas Wołyń will gain a place in Poland’s cinematic pantheon alongside Andrzej Wajda’s 2007 film, Katyń (which, by the way, only gets a 6.8 on filmweb.pl, though the 94% score on rottentomatoes.com more accurately reflects its critical reception). Most importantly, Smoleńsk is based on a fabrication, whereas Wołyń deals with a massacre that actually happened (though, as at least a couple of others have pointed out amidst the near universal praise, there are some important errors of omission and commission in Smarzowski’s film, too).

But in an important sense, all of the aforementioned films fit together, because all of them are Polish films about Polish victimization, about what “they” have done to “us”. As such, they fit within a very familiar story-line about Polish history, one that I’ve been trying to call into question for quite some time. There are many strictly historiographical debates about how to properly contextualize and explain collective instances of mass violence, particularly those that took place during the Second World War, but that’s not my only area of concern. Even more important is the pernicious role that martyrology plays in the present—a danger that the current regime in Poland is demonstrating all too well. When we see the past as a tale of suffering and victimization, it is all too easy to assume that the present and future must be characterized by similar historical dynamics. That’s precisely why the Smoleńsk conspiracy theories make so much sense to so many Poles: the leaps from coincidence to analogy to perceived historical continuity are all too easy to jump across. And if that continuity is real, then we must be vigilant. “Never again,” in this context, doesn’t mean “let’s be on guard against the emergence of comparable evils in other settings, involving other players in other contexts.” Instead, it means “let’s be sure that they never do this to us again.” Not only does this encourage national stereotypes and tense international relations, but it promotes authoritarian politics in domestic affairs. After all, if the nation is under threat, it cannot afford the luxury of liberal democracy.

I’m not arguing that there is some sort of inexorable slippery slope between martyrological history and nationalist dictatorship—that would be a silly overstatement. But I am arguing that the former facilitates the latter, in the literal sense of making it easier to achieve and sustain. And at times like the present, when an authoritarian Polish government is explicitly promoting a victimological approach to history, and using the educational system to create a new generation of “patriotic” Poles (militaristic, obedient, Catholic, and committed to the cultivation of national grievances)—at times like these, the inevitable political appropriation of a film like Wołyń will trample upon the author’s (undeniably good) intentions.

With these thoughts in mind, I recently dashed off the following poorly stated comment on Facebook:

I’m inclined to believe that the best films or books about historical crimes are made when the director/author identifies him- or herself as a member of the same nationality as the perpetrators, not the victims. A film that attempts to explain “how could people like me have done such horrible things?” is usually going to be much more nuanced and insightful than one that cries out, “look how much we have suffered.” The former promotes human understanding (even the really uncomfortable kind), whereas the latter very easily devolves into martyrology and insatiable grievance.

I shouldn’t have been surprised when I received a lot of criticism for these remarks (some of it right there on Facebook, some of it through other channels). I can easily dismiss the ad-hominem attacks or the simplistic insults, but I do respect the reasoned counterarguments that several people offered. Most compelling was the Kantian challenge: would I really be willing to universalize my claim, and suggest that Germans rather than Jews should write about the Holocaust, or American whites rather than blacks should write about slavery?

No, of course I would not make those generalizations, nor would I say that Poles cannot write about Polish victimization. Of course they can. But there are serious difficulties that must be addressed.

I want to proceed very carefully, not because I’m afraid of violating any polemical taboos, but because I sincerely recognize that this issue is extraordinarily complicated. The most important point to emphasize—not as a tossed-off qualification, but as a fundamental point—is that I’m thinking here about broad tendencies and not universal rules. As a historian I must believe that it is possible to stretch one’s own subject position, because otherwise historical empathy would be impossible and our discipline would be reduced to the role of cultivating the memory of one’s own community. As an American who has dedicated his career to writing about Polish history, I refuse to accept such a limitation.

Keeping this in mind, let me formulate my argument in a more systematic and precise way. There are three components to my claim, and I recognize each as worthy of further discussion and reconsideration.

- First Claim:

- If one has an (explicit or implicit, acknowledged or unrecognized) emotional bond with a community,

- and if that community is understood to have a trans-historical continuity that links people in the past with people in the present,

- then it is more difficult (not impossible, but certainly more difficult) to write about episodes of suffering by that group in ways that avoid the pitfalls of martyrology.

- Second Claim:

- When focusing primarily on the suffering of victims in acts of mass violence, it is likely (not inevitable, but much easier) to present the perpetrators as agents of absolute evil (either willfully evil, or trapped within evil structures).

- When focusing primarily on the suffering of victims in acts of mass violence it is likely (not inevitable, but much easier) to locate historical agency among the perpetrators.

- When agency is located outside the primary topic of a historical study, then the point of the study is no longer to ask questions about why or how something happened, because the why or how have been (by definition) positioned outside the main area of study.

- If we are not interested in how or why something happened, then our goal is not to understand in the fullest sense of that word, but to commemorate.

- If the point of our work is to commemorate rather than understand, see my first claim.

- Third Claim:

- It is impossible to truly understand someone without establishing some level of empathetic bond with those whom one is trying to understand.

- Explanations that position historical agents as themselves victims (“brainwashed” or trapped within irresistible structures or systems) just pushes the question back one level without resolving much.

- If one has an (explicit or implicit, acknowledged or unrecognized) emotional bond with a community, it is easier to establish historical empathy with others who claim membership in that community, and harder to establish historical empathy with those in conflict with that community.

- Therefore, in such cases it is easier to develop an understanding of the actions of those within “our” community, and correspondingly harder (not impossible, but harder) to understand the actions of those in conflict with that community.

Those who see their mission as one of commemoration rather than understanding will find this whole train of thought irrelevant. I don’t deny a role for commemoration, I just don’t see that as the task of historians. Commemoration is always and everywhere a political act that is more grounded in the present than in the past. Good history is always political too, but in a different way: good history poses questions and encourages us to see the nuances and complexities of everything around us. Above all, good history builds empathy, which is political in the sense that it mitigates against authoritarianism, intolerance, and violence. Empathy is the opposite of martyrology, and therefore martyrology is not good history.