This Weekend’s Hatred in Poland

Midday last Friday, Professor Jerzy Kochanowski of Warsaw University was talking with a colleague from Germany on a tram, when another passenger got upset that they weren’t speaking Polish. After an angry exchange, Professor Kochanowski was attacked. None of the other people on the tram did anything to intervene. The driver eventually kicked both the assailant and the Professor off the vehicle, telling them to take their fight outside—even though it was obvious that what was taking place was an attack, not a fight. The perpetrator fled the scene, and Professor Kochanowski had to call the police himself. Later he was taken to the hospital to be treated for his wounds.

I posted an account of the attack on Facebook, and related my concerns about the fact that my daughter and I often speak English in public here in Warsaw. A Polish-American activist who was recently named a member of the Senate’s “Polonia Advisory Council” responded to my concerns by writing “How ignorant this comment is! How can you compare the symbolic meaning of English language with German language being spoken in Poland? Are you so clueless as to the role of Germany in Europe then and now?” In a similar spirit, one prominent pro-government journalist wrote, “After what the Germans did in Warsaw, the fact that only now someone got hit in the face for speaking German speaks well for the Poles.”

Let’s set aside the implication that in Warsaw in 2016 it is OK to speak some foreign languages, but not others. Instead, let’s move to the next day. On Saturday, a Warsaw resident of East Asian heritage was riding the metro when a man began shouting at her that she should go back where she came from, and leave Poland for the Poles. This time someone did intervene, stepping between the bigot and his victim, and calling the police (fortunately cell phone coverage extends to the excellent Warsaw subway). With impressive alacrity, they appeared at the very next stop, and the man was arrested.

Finally, on Sunday I was attending the harvest festival in Czersk, a small town not far from here with famous medieval castle ruins. In large letters on the road leading to the festivities, everyone was greeted with the (typically ungrammatical) message, “KOD Jews to the gas Mateusz Kijowski.” Kijowski is the founder of the Committee for the Defense of Democracy (KOD), a nonpartisan organization that has been leading the resistance to the government’s efforts to undermine constitutional legality and the norms of liberal democracy.

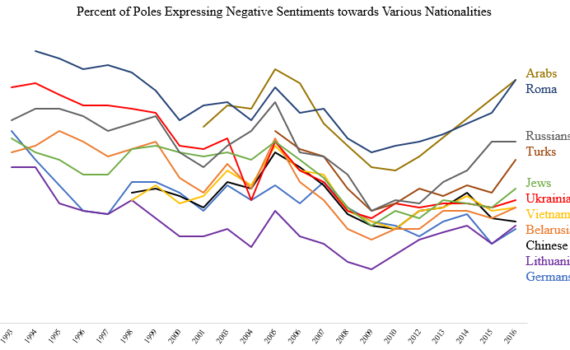

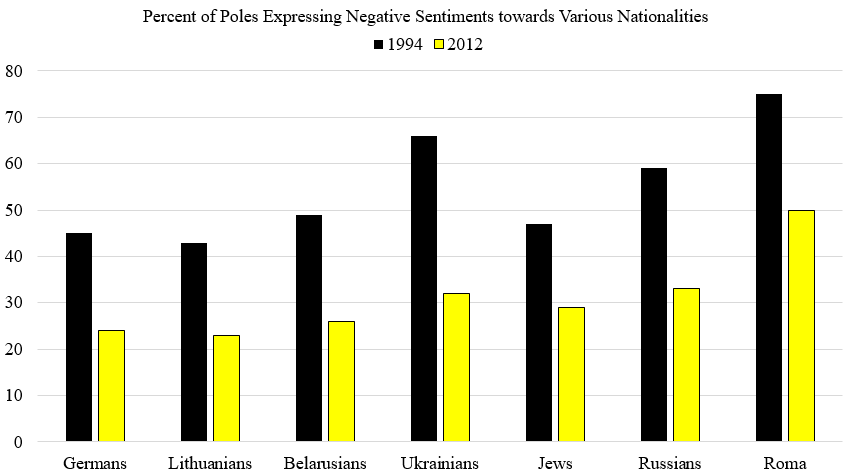

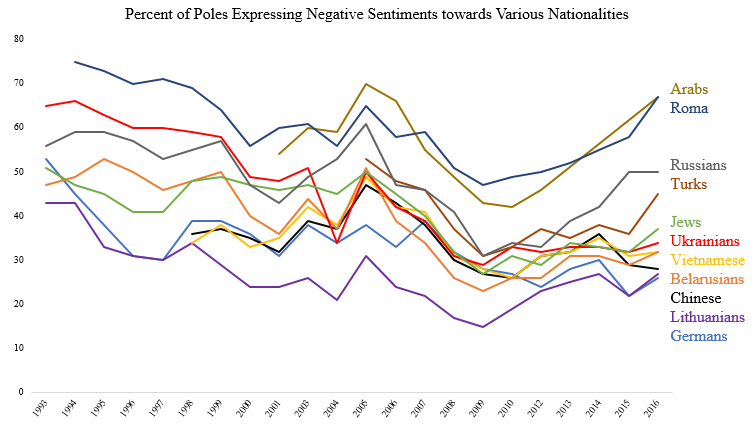

I really dislike arguing from anecdotes, so I’ll be the first to admit that these three examples are isolated incidents. All they demonstrate is that Poland has its fair share of assholes and cretins. For many years, I have been insisting to anyone who will listen that bigotry, xenophobia, and thuggery are problems in Poland—but not significantly more so than elsewhere. Moreover, I’ve argued that antipathy towards foreigners has been declining steadily over the past two decades. Since 1993, a leading survey firm in Poland has been asking people whether they have positive, neutral, or negative feelings towards particular ethnic, national, and religious communities (click here for all the methodological details). As recently as five years ago, it was undeniable that the trend-lines were going in the right direction.

Back in 1994 no one was even thinking about what Poles might feel about people from Asia or the Middle East, but when they were added to the questionnaire (in 1998 for Chinese and Vietnamese, in 2002 for Arabs, and in 2005 for Turks), the trend towards declining hostility was equally evident.

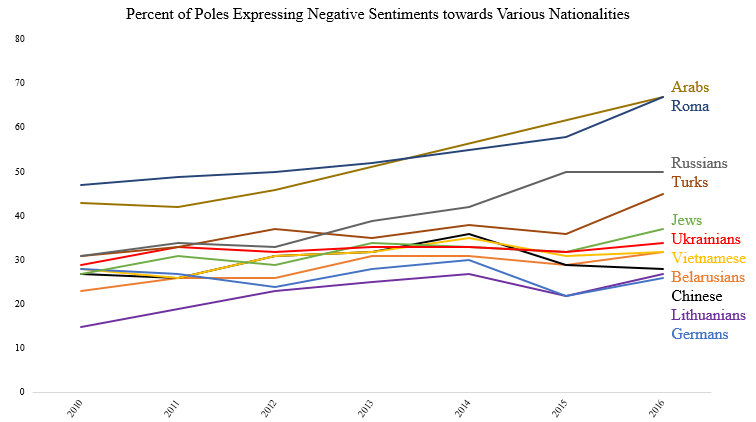

Then something happened.

It is hard to make statistical generalizations over time with a chart like this, because not every group is included for every year. Just taking the communities listed here, and just considering a few years in which all of them were represented in the survey, we see a peak of average levels of antipathy across all groups at 51% in 2005, falling to 31% in 2010, then rising back to 40% this year.

What are we measuring here? Probably not actual sentiments, insofar as people may not be willing to admit to xenophobia or racism if doing so carries a stigma. But I think that is precisely the point: we are witnessing an important shift in what is considered publicly acceptable.

What are we measuring here? Probably not actual sentiments, insofar as people may not be willing to admit to xenophobia or racism if doing so carries a stigma. But I think that is precisely the point: we are witnessing an important shift in what is considered publicly acceptable.

During the communist era, ironically, expressing ethnic hostility brought very little shame. The rhetoric of socialist internationalism had been hollowed out by the “national communism” of Władysław Gomułka, leaving little more than a few empty slogans. Hatred towards Germans and Jews was openly deployed by the communists. While the intelligentsia dissidents of the 1970s and 1980s denounced xenophobia, hostility towards Russians (and less openly, Jews) was common among those opposed to the regime. So when reliable surveys began in the early 1990s, overall levels of explicit bigotry were disturbingly high.

Such views moved into the shadows as more and more Poles came to realize that in polite European society, “nie wypada” (it is not appropriate) to express racism, antisemitism, or xenophobia more generally. In 2005, with the first PiS government, we saw a spike in willingness to tell survey-takers about such feelings, but following their defeat in 2007 a huge drop-off began. When Poland hosted the Eurocup soccer tournament in 2010, it seemed to me that a genuine turning point had been reached. As I argued at the time, the very nature of Polish patriotism seemed to have changed, as nearly everyone gleefully donned the red-and-white. The symbols of national sentiment (the eagle, the flag, the national colors) seemed no more connected to nationalism than the iconography of college football teams back in the United States. This corresponds to the moment, five years ago, when a record low number of respondents were willing to admit to any xenophobic attitudes.

Today the change is obvious. We see it in the survey results, making episodes like those of last weekend feel emblematic rather than deviant. I felt comfortable dismissing the soccer hooligans of 2010 as remnants and aberrations, whereas today they seem to be extreme expressions of themes that have returned to the mainstream of Polish public rhetoric. I don’t think I was wrong then, or now: instead, I think we have witnessed the ebb and flow of what is considered understandable (if perhaps a bit extreme), and what is labeled shameful and beyond the pale.

Right now, many of my friends are despairing, but I’m not. At least, I’m trying to remain optimistic. I look at the sharp downturn of the last couple years and I remember the equally dramatic improvements that came before. Xenophobia in Poland (or anywhere else, for that matter) is a phantasm that occasionally escapes its chains. It does indeed seem to be on a rampage right now, wreaking havoc not only here, but throughout Europe and America. But it will be captured and confined once again. The only question is when.