Kopacz vs. Kaczyński

Things do not look good for Poland’s Civic Platform (Platforma Obywatelska, or PO). As the dust has settled after the surprising presidential elections a month ago, the far-right opposition Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, or PiS) seems to have a clear road to power. The only other group with substantial support at the moment is the nationalistic but ideologically amorphous protest party of Paweł Kukiz, a rock musician who startled everyone by coming in third in the presidential elections. The rise of Kukiz is actually the main story here, because until he appeared on the scene it seemed nearly unimaginable that PiS could ever find a partner for a coalition government, and it remains highly improbably that they could ever win an absolute majority. But a PiS-Kukiz coalition is a very real possibility.

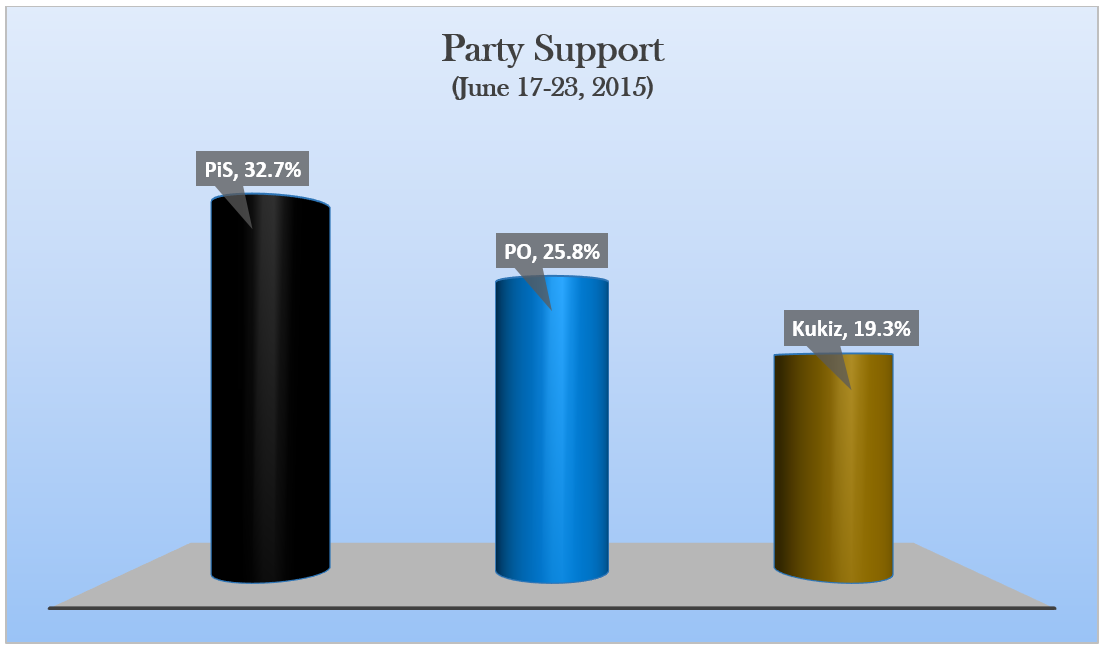

The procession of bad news for PO seems endless. These graphics speak louder than words:

It is very hard to see a way out for PO. In fact, very few Poles (including those who support the current government) think that Prime Minister Ewa Kopacz can retain power: a survey from June 23 revealed that 51% think PiS will form the next government after the Fall elections, compared to only 9% for PO.

The nail in Platforma’s coffin seemed to come with the PiS party convention on June 20, when Jarosław Kaczyński announced that he would not put himself forward as the party’s candidate for Prime Minister, naming instead Beata Szydło, who had far less name-recognition but (as the chart above shows) also far lower levels of mistrust than the PiS leader. This is precisely what Kaczyński did in the presidential elections, fronting a charismatic but previously unknown candidate, Andrzej Duda. Meanwhile, the radicals who have set the tone of the party’s message over recent years have been kept on a very tight leash.

Prime Minister Kopacz, who is also the leader of PO, has taken several important steps to regain momentum. She fired several controversial ministers, replacing them with younger and more dynamic figures. Her message has been combative and sharp, in contrast to the muffled approach defeated president Bronisław Komorowski used in his campaign. But let’s be honest: this isn’t going to be enough. It would seem that the only realistic hope for PO is that Kaczyński (or some other prominent figure in PiS) make some monumental gaff that reminds everybody of the radical tiger hiding behind the friendly lambs of Duda and Szydło. As the old saying goes, the definition of a gaff is when a public figure accidentally says what he or she really thinks. So far in 2015, we haven’t seen those kind of gaffs from the PiS leadership.

With this in mind, I can think of one way that Kopacz could regain the initiative. There will certainly be a series of debates between the main candidates for the office of Prime Minister, and a debate between Kopacz and Szydło would be interesting but unlikely to shift the surveys much. However, there’s something highly unorthodox here: in parliamentary systems, election campaigns are typically led by the leaders of the respective parties. Kaczyński is not resigning from his position as PiS party leader—in fact, Szydło has already had to face accusations from skeptical journalists that she is merely fronting for man who will be the power-behind-the-throne. The last time PiS held power, the office of Prime Minister initially went to a lesser-known figure, Kazimierz Marcinkiewicz, but Kaczyński pushed him aside after 9 months and took power himself . Given this precedent, the PO campaign should insist that any debates be between exact peers: party leader vs. party leader, Kopacz vs. Kaczyński.

This is a dangerous move: Szydło could respond that it is sexist to imply that a woman couldn’t be a genuine leader without a man exerting real power. In the abstract such a charge would seem plausible, and under other circumstances PO would be in a real bind because of this. But because of Kopacz’s own gender, and because of Kaczyński’s history of using front-men (with an emphasis on men), I think this risk is mitigated. Every observer of Polish politics over the past decade knows that Kaczyński values discipline and obedience very highly, and has little tolerance for those who deviate from his line. In fact, the club of ex-politicians in Poland is populated by a great many people who threatened Kaczyński’s position within PiS and were pushed out of the party—even if their only threat was the fact that they were more popular than their leader.

What I am proposing would be ugly. Instead of a campaign on the merits of each party’s policy proposals, this would be a fight based on fear. On the one side, PiS would continue to repeat that Poland is “a country in ruins” (probably their favorite mantra), while PO would play to the fact that Kaczyński remains one of the most distrusted men in Poland. His negatives are only surpassed by Antoni Macierewicz (also of PiS), Janusz Korwin-Mikke (a libertarian fringe candidate), and Janusz Palikot (the fallen star of the moribund Polish left). A hard-fought negative campaign would go against the instincts of the PO leadership, most of whom are policy wonks, technocrats, and well-mannered (in public, at least) liberals. And it would leave a great deal of wreckage in its wake, on all sides. But it may be Kopacz’s only chance.