In the coverage of last week’s Polish presidential election in the Western media—and some of the Polish media as well—the words “left” and “right” have generated a great deal of misunderstanding and confusion. Here are some headlines:

Part of the problem here is a familiar challenge: how to translate political labels. “Right” in English is not quite the same as “prawica,” “recht,” or “droite.” For that matter, “right” in American English is not quite the same as “right” in British English. Most obviously, in the United States “right” and “conservative” imply a belief in unconstrained free markets and an opposition to organized labor. It was amusing to see right-wing news outlets here in the US celebrate Andrzej Duda’s victory, because no member of PiS (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, Law and Justice) would ever find a home within the Republican Party. True, they would share a common foundation of nationalism, Christianity, and hostility towards gay rights and women’s rights, but they would be polar opposites on every economic issue. American Republicans would enjoy hearing Duda condemn liberalism—until they realized what he meant by that word! Here we take “liberalism” to refer to the conviction that capitalism must be given a human face through strong government regulation and active labor unions—positions advocated by our “left wing” Democratic Party.

Although the translation problems within Europe are less extreme, they are still significant. When a French politician identifies as a “conservateur,” would his or her positions line up with someone in Poland characterized as “konserwatywny”? There would be a lot of overlap, to be sure. But just to give one example, it was the “conservative” and “right wing” government of Sarkozy that adopted harsh measures to enforce laïcité, something that would be identified with the left—even the extreme left—in Poland. And how would a member of PiS respond to the fact that the “conservative” David Cameron described the introduction of same-sex marriage as one of the accomplishments that gave him the most pride?

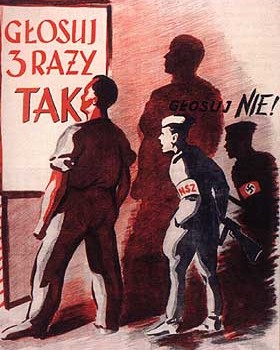

Even deeper than these national differences in terminology, however, is a fundamental question of interpretation about the Polish elections themselves. Did the vote mark a victory for “the right” in anyone’s sense of that word? Insofar as President Duda describes himself in those terms, obviously it did. And insofar as PiS now enjoys unexpectedly strong momentum going into next fall’s parliamentary elections, then certainly the right has triumphed.

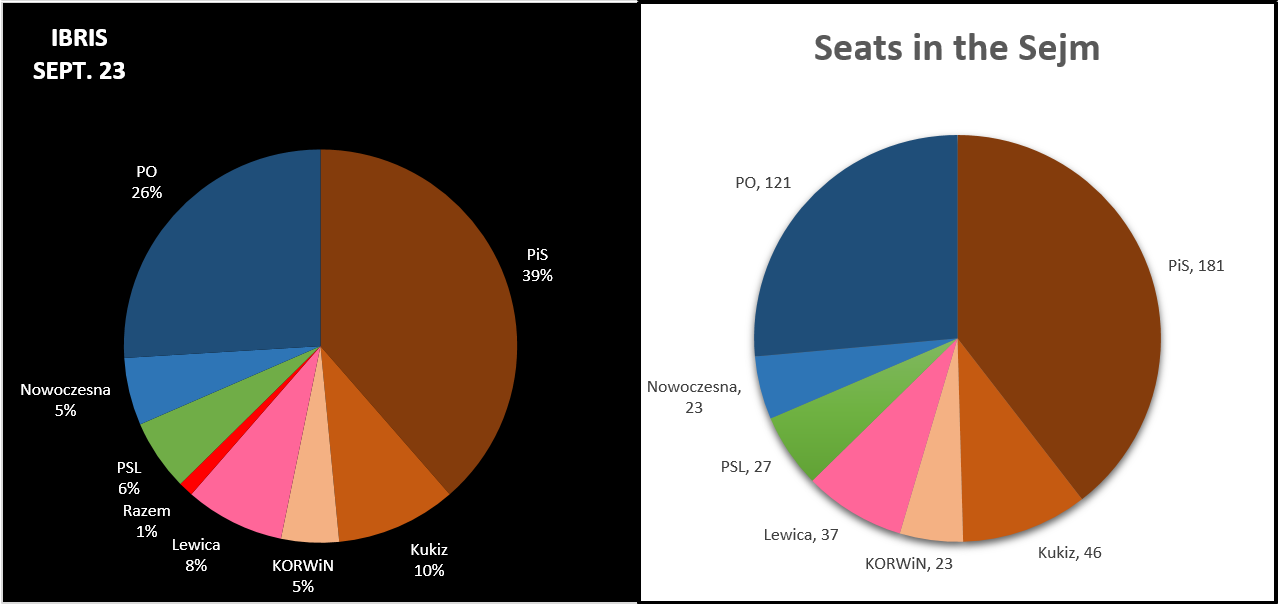

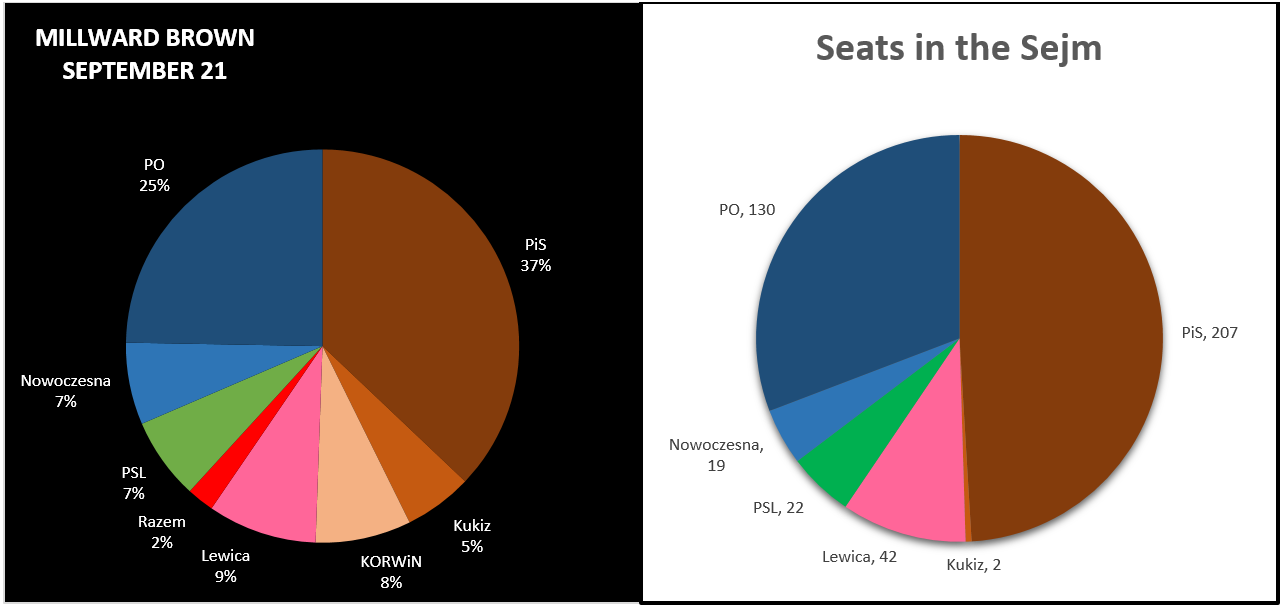

A closer look at the peculiar dynamics of this election, however, should give us pause. Let’s break down what happened more precisely. The core support of PiS is only about 30% of the population, certainly no higher than the 35% that Duda got in the first round of the election. The most recent party preference survey by IBRIS has PiS at 29.7%. This is a party that promotes three main principles: 1) a desire for a strong interventionist state, more equal distribution of wealth, and strong labor unions; 2) a conviction that foreigners are undermining Poland’s national interest at home and abroad, and a plan to identify and bring to justice the politicians who serve those foreigners; 3) a fear that Catholic values, particularly regarding issues of sexuality, gender relations, and reproduction, are under siege and must be defended by the state. This particular trio of values is not widely shared outside the PiS core constituency; in fact, it would probably win the support of a segment of the population that’s even somewhat smaller than the PiS electorate.

If that is true, then how did Duda win? The difference consists almost entirely of those who voted for Paweł Kukiz in the first round (20.8% of the total). Kukiz is not affiliated with any political party. He was briefly with the governing PO (Platforma Obywatelska, Civic Platform), and later he shifted loyalties to some extreme nationalist organizations. His campaign, however, was entirely outside any of our familiar categories. His economic positions were what Americans would call libertarian, and what Europeans could call liberal—but he rarely talked about the economy and he dodged questions on this topic. His only big issue was advocacy for electoral reforms that would replace proportional representation with single-mandate districts. Ironically, this stance is shared by PO and opposed by PiS (along with every smaller party, which would be entirely eliminated from contention under the new system). Some people voted for Kukiz because of this issue, but exit surveys suggest that his biggest bloc of supporters came from those 18-29 years of age, living in large urban areas. This demographic is the true swing vote, and what they do in the fall will determine Poland’s medium-term future.

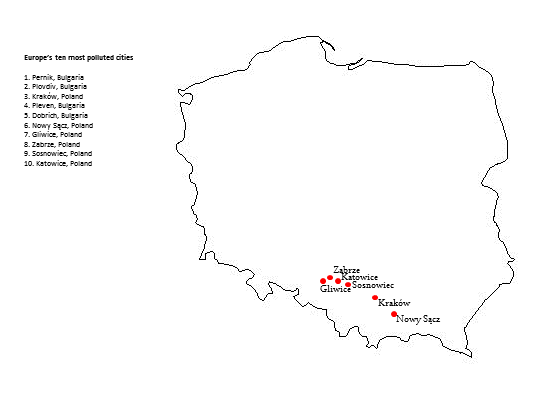

So what do those urban young people want? This is not a natural cohort for PiS, because they tend to be too secular and cosmopolitan for that party. They voted for Duda and a great many of them might even vote for PiS in the fall, but they will become disillusioned very quickly. On the other hand, this is not a natural cohort for PO either, because this is a population that feels no satisfaction about Poland’s recent economic successes. The official unemployment rate among those age 15-24 currently stands at around 23%–lower than it was a couple years ago, but still very high. This is an age group that faces a job market without adequate prospects for long-term job contracts: they are the so-called “precariat,” too often getting by with “junk jobs (umowy śmieciowe) that leave them without adequate health and retirement benefits.

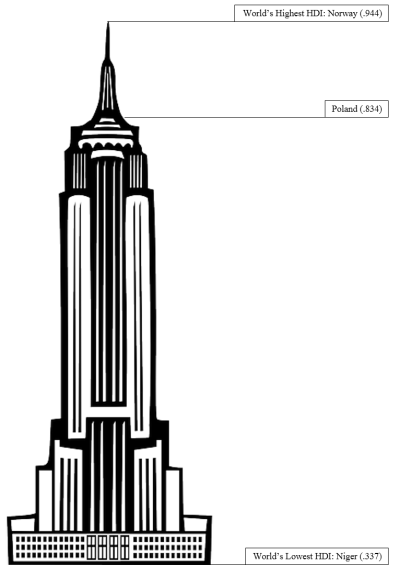

Even setting aside those concrete issues, the main issue for young people in Poland today is a question of comparisons. 25-year-olds in Poland have no recollection of the hardships of the period before 1989; in fact, they don’t even remember the tumult of the 1990s. They came into a world in which Poland was already firmly embedded in Europe, and in which the gap between their lives and the lives of their contemporaries in Germany or France was narrower than ever in history. But that last phrase—history—is the key. I could present statistic after statistic about how much closer Poland is to European norms (indeed, I’ve done so on this blog), but that doesn’t take away from the fact that the gap remains. And precisely because Poland is now closer, that gap is experienced as inexplicable and frustrating. For a young Pole in the 1980s, the world of “the West” was a fantasy land, and the most typical reaction to exposure to the West was a desire to live there. For a young Pole in the 2010s, that world is still significantly better but now it’s within a shared frame of reference, and the typical reaction to exposure to the West is a desire to make Poland the same—or anger over the fact that it isn’t.

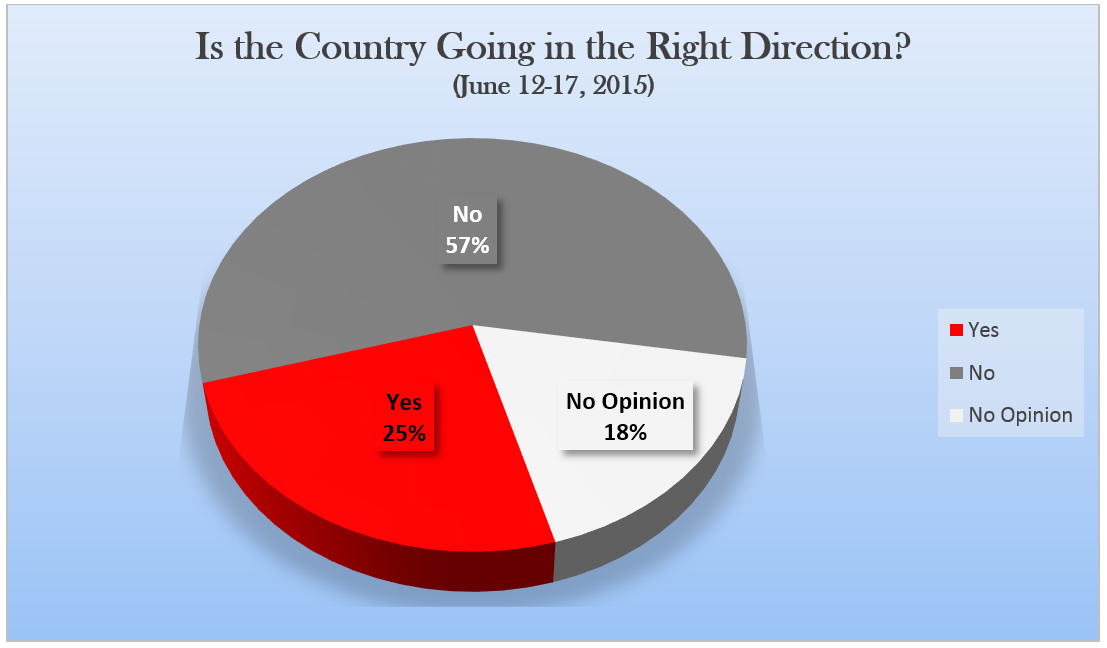

In other words, this isn’t quite the same problem as those expressed by rebellious young voters in southern Europe, who have seen their lives get significantly worse. It is a different rebellion, and it requires a different response. The anger of the young needs to be acknowledged, respected, and channeled productively. If someone can do that, whatever ideological label they use, they will be politically successful. Unfortunately, the more realistic outcome for the immediate future is that these voters will be drawn to a vote against everything, not a vote for anything. This is a group that seems to want solutions, but doesn’t trust any of the existing parties to deliver those solutions. PO can’t win them back with offers of programs to address their material concerns. PiS can win them with unrelenting attacks on PO, but that will work only if the nationalism, religiosity, and cultural conservatism of PiS is sufficiently pushed to the background (which Duda did, but which Kaczyński probably can’t do).

So the story of the week is not a Polish “turn to the right”. It’s a story of how the right was victorious thanks to the decisions of a cohort of yet-to-be-labeled young people who aren’t likely to stay with PiS for very long. Where they will go, and what labels we will eventually find for them, remain very open questions.