Now that the dust has settled after one of the most momentous elections on recent Polish history, it’s time to take stock and think about what lies ahead. Over the past several days I have been gathering responses to a survey that I distributed via the academic discussion forum, H-Poland (540 individuals). This group encompasses scholars from around the world who work in the field of Polish Studies, in any discipline. I received 63 responses, of whom 77% held a doctorate (the remainder were mostly graduate students). Slightly more than half of the respondents were historians, with the other half representing anthropology, sociology, political science, economics, and the humanities.

The complete survey results can be found below. To sum up the responses: most of these scholars see difficult times ahead, but few are predicting an apocalypse. Most believe that the fears (or hopes, depending on one’s perspective) that PiS will fundamentally transform the political system in Poland towards a more authoritarian, anti-liberal regime are exaggerated. Few respondents foresee a “Budapest on the Vistula,” to quote the oft-cited allusion to the political model set by Viktor Orbán in Hungary, but most respondents do anticipate some challenges ahead. A large majority expects the state to use public media to propagate the PiS message, and to redirect academic and cultural funding in ways that will encourage their worldview, but not many envision widespread censorship or blacklisting. Although the new government has promised to exert greater political control over the judiciary, few of the surveyed scholars believe that this will fundamentally alter Poland’s legal system or facilitate the use of the courts against political foes.

Opinions are mixed about the new government’s promises to improve Poland’s economy and spread the benefits of growth to a broader share of the population. Again, few predict a disaster, but equally few accept PiS’s campaign promises at face value. If we score the responses to all the economic questions on a scale from one (signifying the most pessimistic answer) to 4 or 5 (signifying the most optimistic), we get a range of 4-18 possible points. Both the median and the mean were at 10. Most respondents believe that Poland’s economy will slowly grow, that inequality will remain roughly as it is now, that the unemployment rate will hold at its current low level, and that emigration figures will either stay the same or slightly increase.

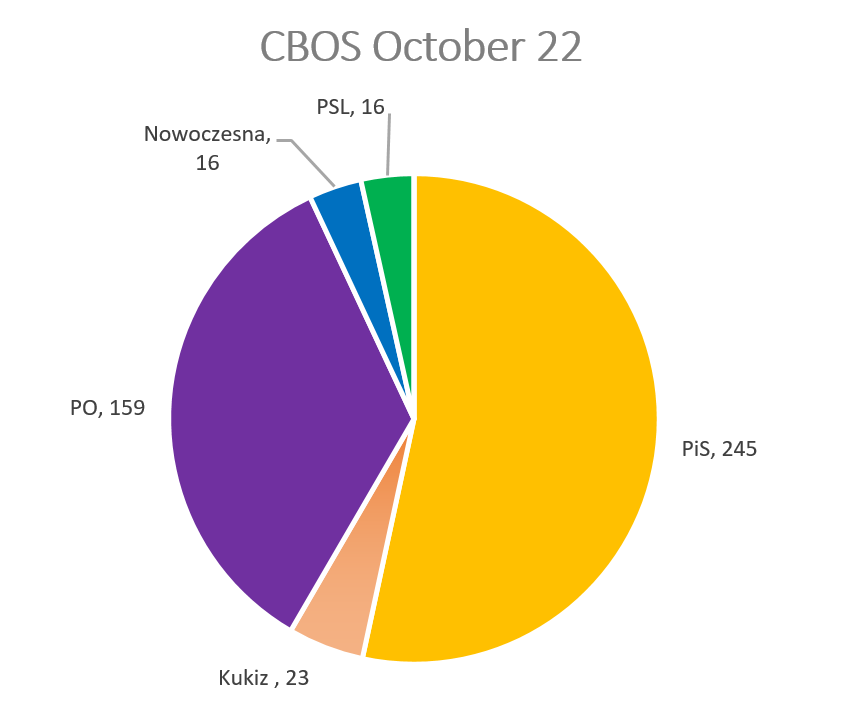

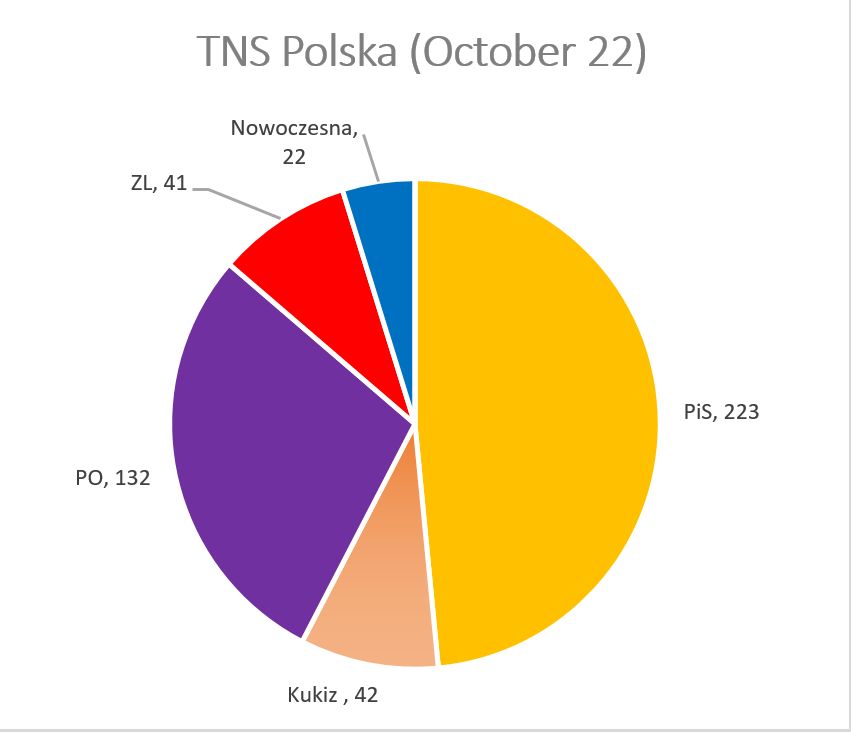

About half the respondents believe that PiS will lose power during the next round of parliamentary elections (no later than 2019). Of those who predict a second PiS term, most think it will only be possible by forming a coalition with other right-wing parties. Very few are worried that Kaczyński will resort to extra-constitutional measures to hold on to power. If that’s true, then it is significant that he lacks the votes needed to change the constitution. Opponents of PiS often quote Kaczyński’s ambitions to restructure the Polish state, and many of his more outspoken supporters have expressed a longing for a radical renewal of Polish public life, but that can’t happen without violating the existing constitutional constraints. Orbán was able to go as far as he did only because Fidesz possessed the 2/3 majority required for constitutional amendments; Kaczyński is well short of that figure, even if we include the votes of some people outside PiS who might support such an undertaking.

During the election campaign, some of PiS’s opponents painted a frightening vision of the future. For example, the magazine Polityka warned against a looming authoritarianism, and Adam Michnik foresaw a “catastrophe” brought about by a new wave of “xenophobia.” On the other hand, the Catholic magazine Niedziela (Sunday) dismissed out of hand concerns that PiS would introduce an authoritarian theocracy, insisting that a larger problem was the “marginalization of the Church” in today’s Poland. The Catholic daily Nasz Dziennik proclaimed that the PiS victory was a triumph over a concerted propaganda campaign by the old government and “most of the leading media.” In other words, before the election the Catholic right felt excluded and oppressed, and today many on the secular left fear that the new government will violate democratic norms. I doubt many outside observers would confirm claims that Catholics were in any way “marginalized” in Poland up to now (quite the contrary!), and based on this survey, it seems that only a minority of scholars fears that the new government will seriously weaken the country’s democratic, pluralistic foundation.

Personally I am inclined to share this cautious optimism, with an emphasis on the adjective “cautious.” But recent history in Hungary, Turkey, and Russia, alongside the growing strength of groups like UKIP in Britain or the National Front in France, should remind us that vigilance is always warranted. PiS may fail to fundamentally transform Poland—indeed, they may stick to the rather mundane issues that they emphasized in the campaign and not even attempt any systematic reforms. Maybe Polityka and other left-of-center voices have been crying “wolf.” I sincerely want to believe that this is the case. But when hears the howls of the pack so clearly in the distance, it pays to stay on guard.

______________________________

Survey Results

______________________________

______________________________

______________________________

______________________________

______________________________

______________________________

______________________________

______________________________

______________________________

What other predictions do you have, not covered in the questions posed here?

- An open question is the future attitude of Andrzej Duda towards the government.

- Changes in Poland’s foreign policy. I suspect that PiS will unsuccessfully try to join the Normandy group. Polish-French bilateral relations will improve, whereas relations with Germany will cool down. If Brexit takes place emigration from Poland will drop down. I don’t think that Poland is facing the risk of Orbanization, but PiS may safely govern for 4 years. It may win the next elections, but strong opposition will continue to exist and challenge the government. Having said that, I predict the disintegration of PO and total marginalization of the left. One fact we have to account for in our predictions is that PiS of 2015 is NOT the PiS of 2005 or 2010.

- Deterioration of relations with EU countries, especially Germany. Higher tensions w/ Russia.

- In 4 years, voters will be sick and tired of PiS and will vote them out of power (repeat of 2007)

- Let’s not forget about Nowoczesna and its potential to play some meaningful role in future.

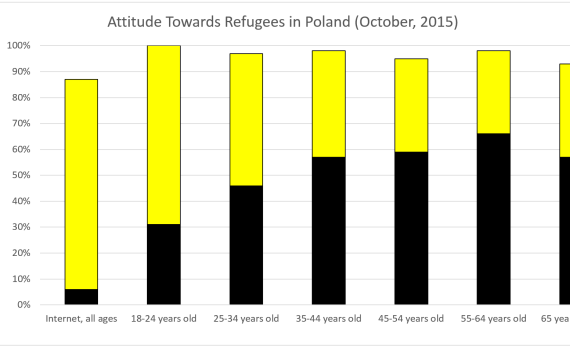

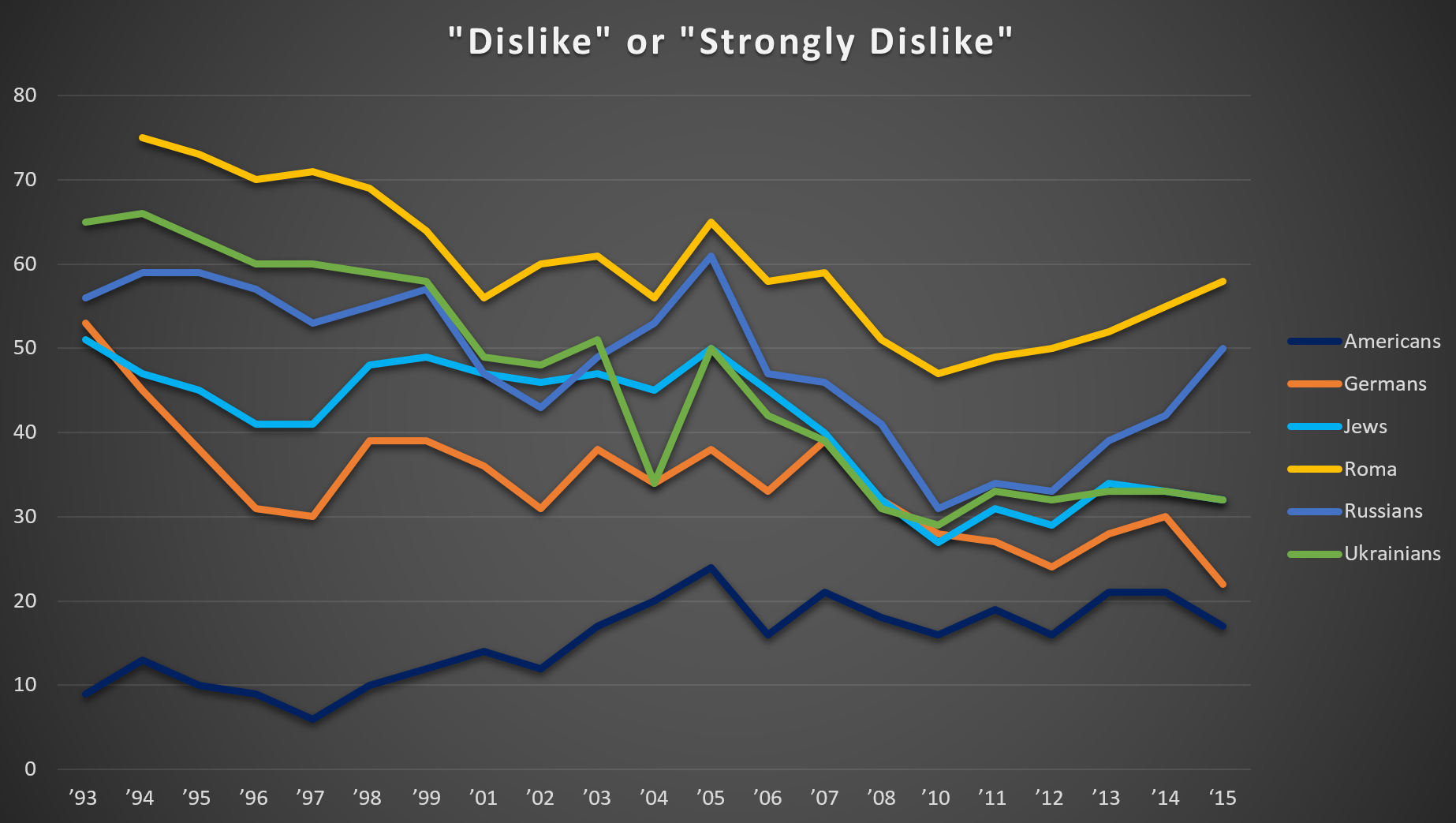

- Manifestations of xenophobia will increase

- Nowoczesna could become a bigger player, perhaps becoming the base for a new center-right party that will succeed PO.

- PiS will lose power but its views, as well as views represented by forces of the far right will remain permanent, “normalized” element in Polish political landscape. Also Platforma, if returns, will have to include them into the political language.

- PiS will return to power but will not be more popular than now – 30-35%. after two stints in office, it will disappear (see trajectory of SLD and PO on this)

- PiS’s intrusive promotion of Catholic Church’s worldview will polarize the society even more. Religious Catholic will become even more extreme and relaxed Catholics will be pushed away from the Church stronger and faster than today.

- Poland will turn right along with so many other countries in Europe at the present, but there will be no major changes since a strong relationship with the EU remains a need. PiS does not have the votes to change the constitution (at the moment), so I do not see any major lasting effects unless that changes.

- Popularity of PiS will fall, there will be a split in PO, new free market – conservative party based on PO and Nowoczesna will emerge

- Rise of nationalism and increased influence of the Catholic Church e.g. religion will be tested on matura at the end of H.S.

- some of these questions include serious mistakes. There are no state-owned media, for instance (do you think about a few among more than hundred TV stations?). Other mistakes: the PO government pressed prosecutors and judges (e.g., Stanisław Kociołek case, Korwin is not a right wing politician, Kukiz has not any political program, etc. In Poland we are very happy because of this change. Many hopes…

- Besides, I predict that Jarosław Kaczyński will betray his wife twice a month. I think that this so-called “survey of predictions” in politically biased and posed questions are not based on real knowledge of social situation of Poland. For example: there are following answers on the question: “What will happen politically when the current government’s term expires in four years?” 1. PiS will be enormously popular and will be returned to office with an even greater majority 2. PiS will lose popularity, but forces further to the right (Kukiz, Korwin, or some not-yet-created party) will increase their strength and allow a continuation of right-wing rule in Poland 3. PiS will lose popularity but remain in power through fraud or the imposition of emergency rule 4. The far right will lose support and Platforma Obywatelska will return to power 5. The right in general will lose support and a leftist government (Zjednoczona Lewica, Razem or some not-yet-created party) will take power” Why did an author of the survey exclude an answer: “PiS will lose popularity and will lose next election” This situation already took place in Poland in 2007.

- That Poland will be become a rather unpleasant nationalist outpost on the fringes of the EU, having alienated just about all its neighbors!

- The Church will increase its influence; we will see the development of an array of parties on the right; Poland will play an increasing role in the East, as Putin continues to pursue an assertive foreign policy

- The PO will make a greater effort to better articulate its policies to Polish citizens living in Easter Poland and in rural areas.

- The question is how far Kaczyński will maintain the pro-state impulse of his dead brother, and how far it will try to instrumentalize the church that far that he himself will be its puppet, the first option results in the Hungarian path, the second in Potugalian – Salazarization.

- The role of Catholic Church will be (even) greater.

- There will be de facto laissez-faire economic policy with pro-business legislation, but covered by slogans and gestures of social solidarity. Polish policy towards the west will be full of nationalistic gestures, but without major breaks in continuity. Polish Ostpolitik will pursue a tough line on Russia, which might paradoxically result in a greater accommodation with Russia as Putin will search for a way to break out of diplomatic isolation.