The Polish Elections: What is at Stake

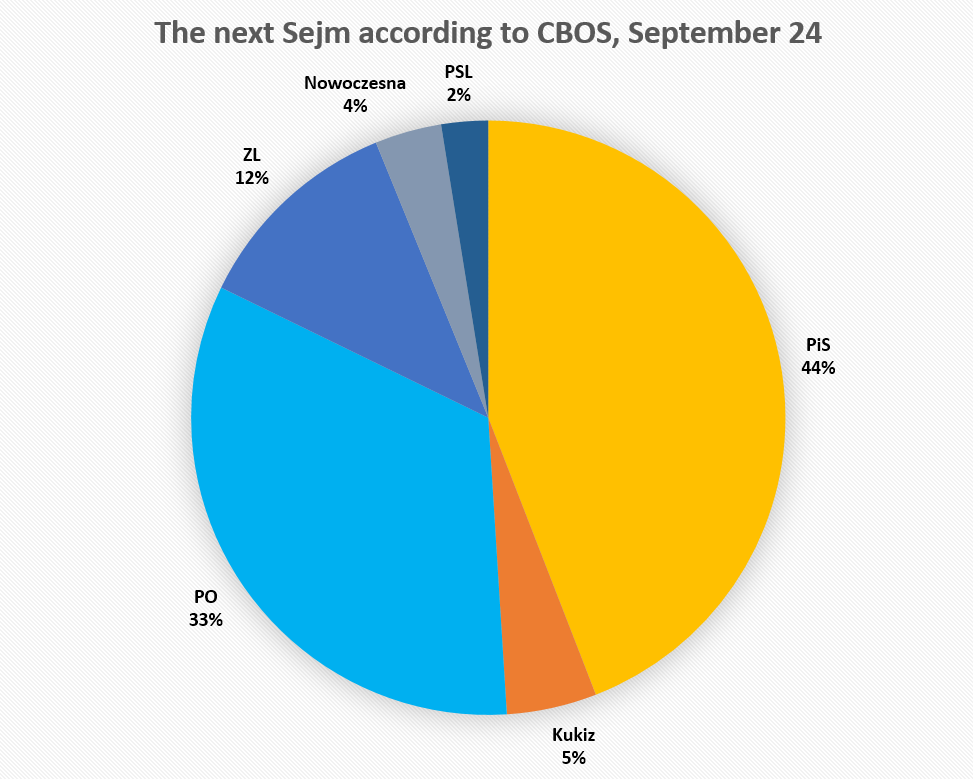

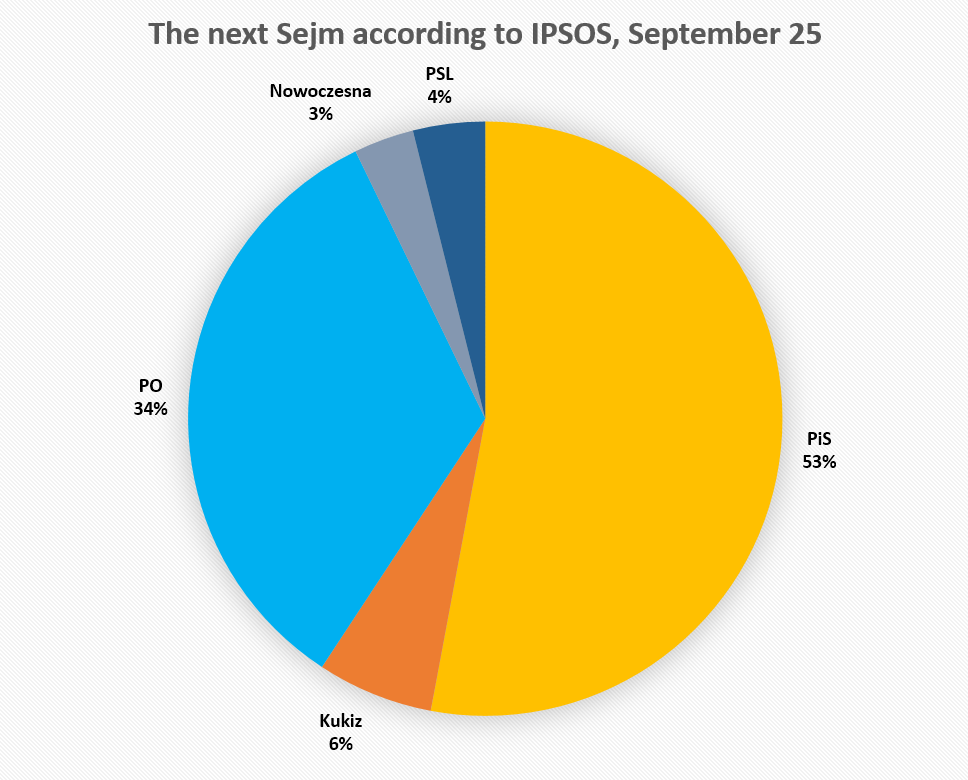

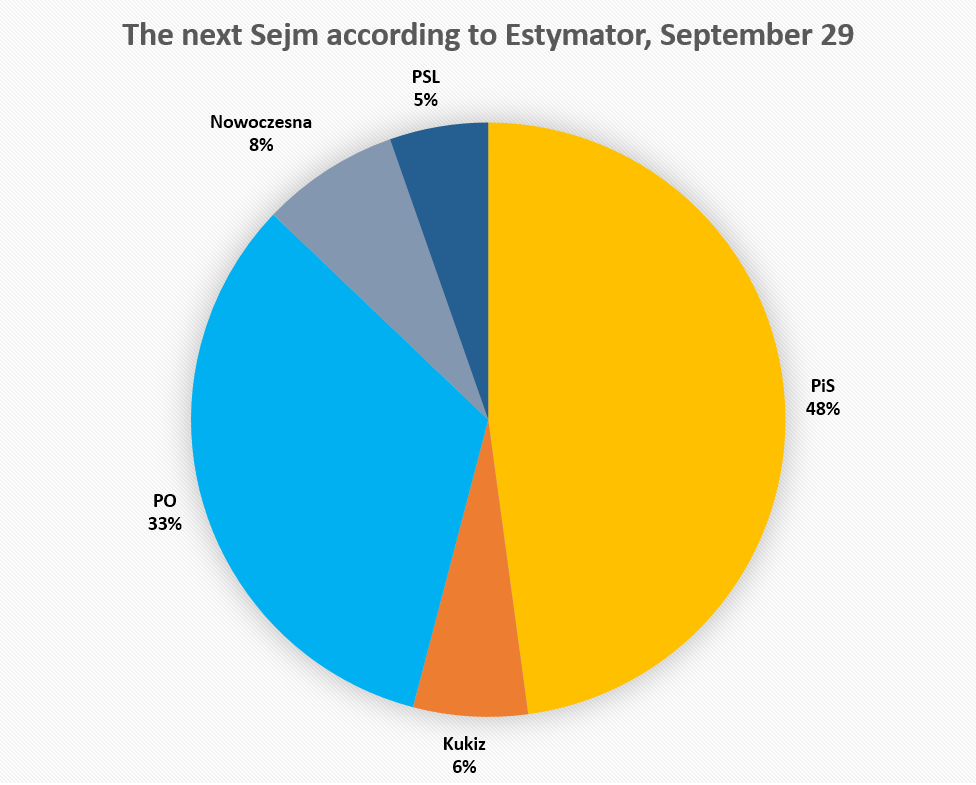

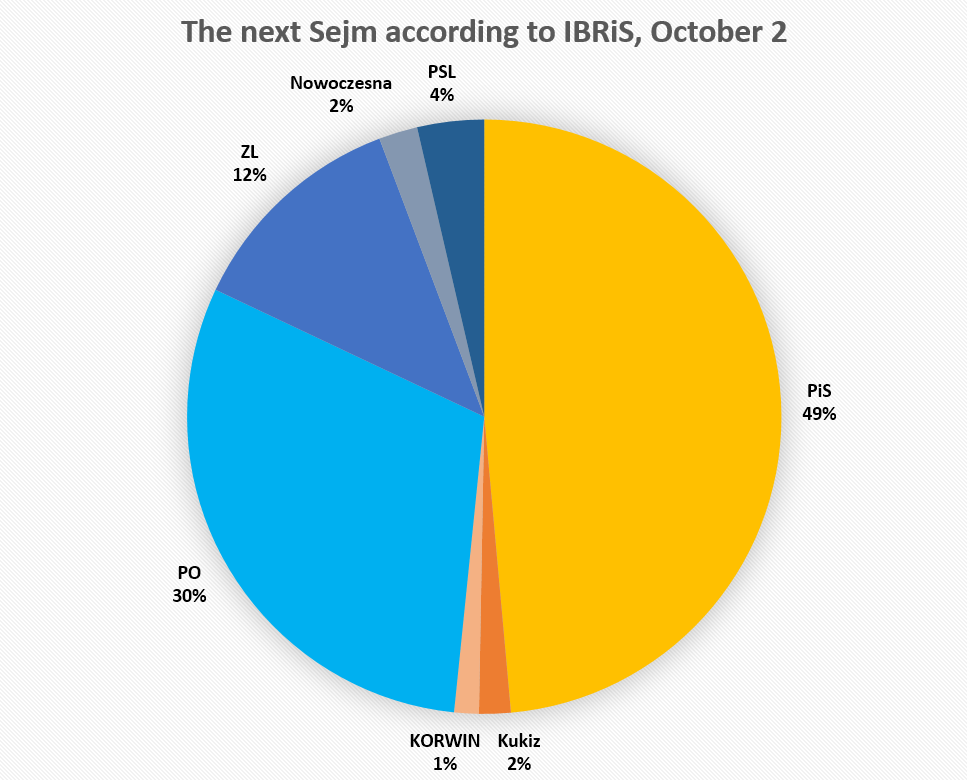

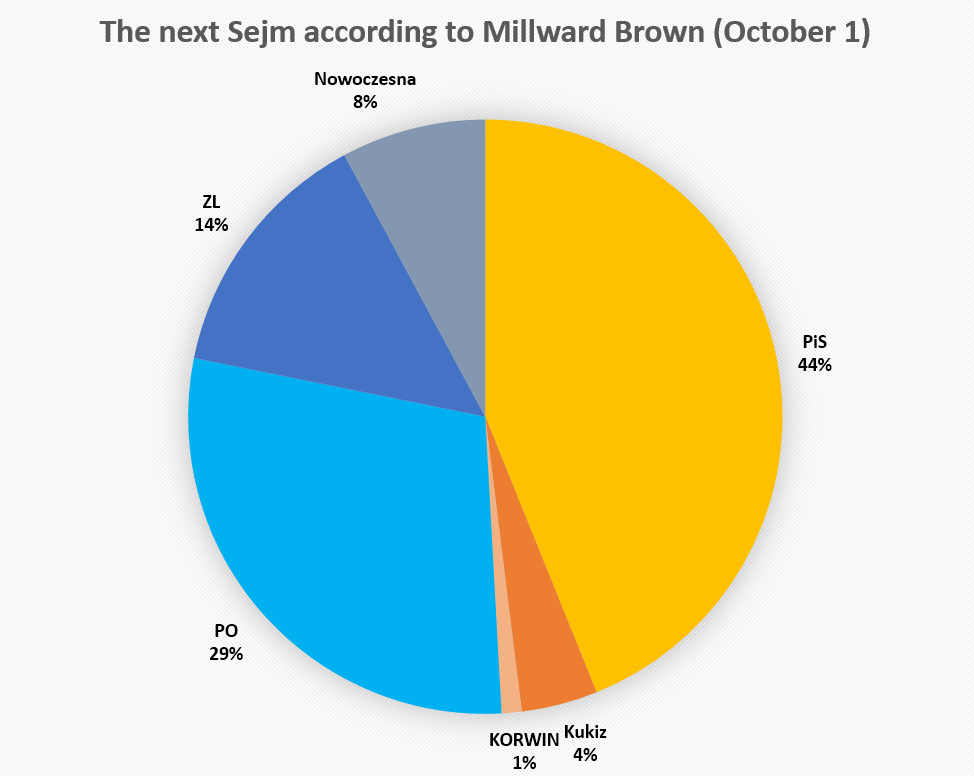

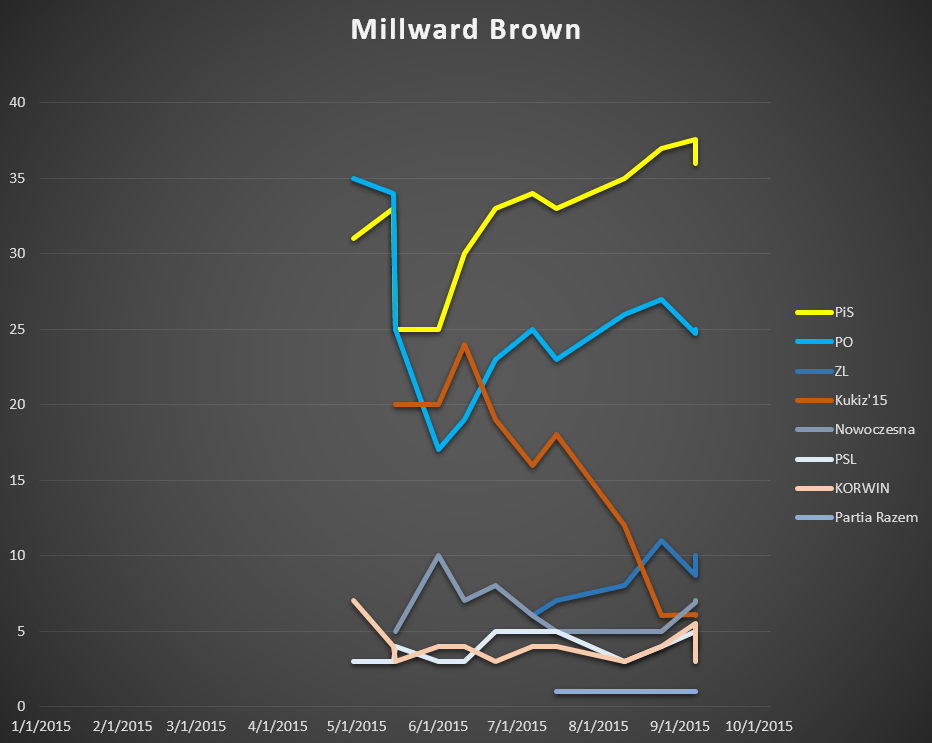

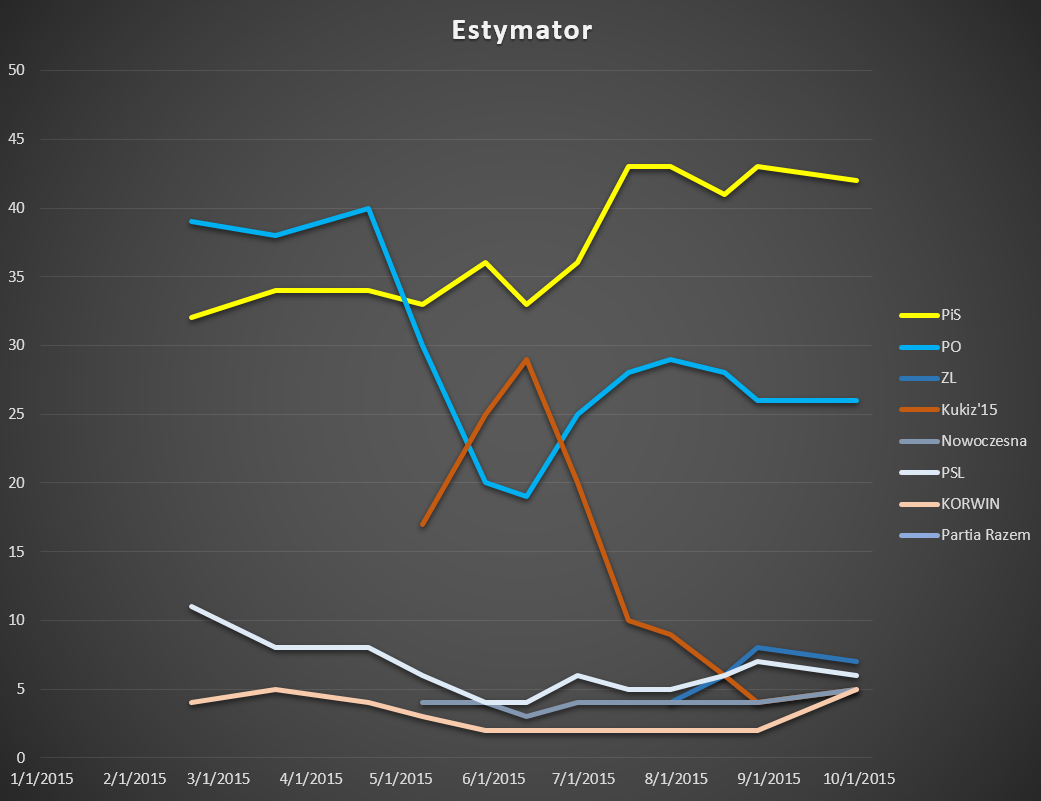

As we move closer to the Polish elections on October 25, there has been some movement in the polls but no dramatic changes. Law and Justice (PiS) remains in first place, with Civic Platform (PO) trailing well outside the margin of error. The collapse of the Paweł Kukiz phenomenon continues, so now there are six parties hovering around the 5% minimum needed to win seats in parliament. As I mentioned in my last post, everything depends on which of those smaller parties make it into the sejm. It seems nearly certain now that PiS will have more votes than any other party, probably around 35%. That is more than they got during the last elections (when they came in at 30%), though their rise has not been nearly as dramatic as PO’s fall (from almost 40% last time to somewhere around 25% now). At this point, the question is not whether PiS will win, but whether they will be able to build a stable coalition. Of the five most recent surveys, only one shows PiS obtaining enough seats in the Sejm to hold a majority on their own. Two surveys show a possible majority coalition for PiS, and two show a configuration that could allow a broad center-left bloc to keep PiS out of power. See below for the detailed charts.

Stepping out of the weeds of this complicated election campaign, it is important to recognize how misleading it is to think of this in terms familiar to Anglophones. I have been calling PiS “far right” and PO “center right,” and that’s accurate in a superficial sense. But the stakes of this election are much higher, because the ideological battle now underway is not between two parties with differing policy ideas or even different long-term goals. Rather, this is a struggle between two competing visions of what sort of political system Poland should have. On the one side are a range of parties that accept the broad outlines of liberal parliamentary democracy as established in the current Polish constitution, with familiar protections for civil liberties and individual rights, and with a commitment to the norms of European politics and international relations. On the other side are those who long for another kind of Poland, one that is more cohesive domestically and more assertive internationally. They hope for a political system that will uphold what they consider traditional Catholic values and resist the incursions of “foreign” ideas and ideals. Many explicitly call for a new constitution and the declaration of a “IV Republic” (overthrowing the current state, which is known as the III Republic), though explicit calls for revolution have been muted during the campaign. They admire what Viktor Orbán has done in Hungary, though his flirtations with Vladimir Putin have silenced the one-popular slogan of creating a “Budapest on the Vistula.” Ironically, this group’s worldview is not that different than Putin’s, though their nationalist hostility towards Russia is far too strong to allow them to perceive such parallels. The leader of PiS, Jarosław Kaczyński, is convinced that the leaders of PO conspired with Russia and/or Germany in order to stage the crash of the airplane carrying his brother, then President Lech Kaczyński. He has spoken of the need to take power in order to bring those responsible for this supposed plot to justice, and called for a thorough transformation of the judicial system in order to strip prosecutors and judges of their autonomy so that the guilty can be punished without the constraints of petty legalism. He intends to reform the educational system—including higher education—so as to ensure that it promotes Polish patriotism and maintains the unity of the nation. The bond between Church and state is already quite strong in Poland, but PiS would expand it further by outlawing abortion entirely, rolling back gay rights, banning in vitro fertilization, etc. Their proposed new constitution would include affirmations of Poland’s Catholic identity and dedicate the state to God.

An observer who has been following the public statements of the rival parties during the election campaign would be forgiven for not recognizing the picture I’ve just drawn. Lech Kaczyński himself has been almost invisible, replacing himself as the party’s standard-bearer with Beata Szydło, who is designated to become Prime Minister in a future PiS government. Many others in the PiS leadership are similarly quiet, because Kaczyński understands that the vast majority of Poles are strongly opposed to the sort of regime described above. PiS has been campaigning on the slogan of the “IV Republic” for more than a decade, and aside from a brief (and disastrous—both for Poland and for PiS’s own approval rating) period between 2005-2007, the party has been in the opposition. So this year Kaczyński put forward Antoni Duda for the presidential campaign last spring and Ms. Szydło for the parliamentary campaign this month. The official party platform stresses pocketbook issues that are widely popular: increased spending for the poor, a decrease in the retirement age, laws protecting Polish businesses from foreign competition, etc. Even some on the left have suggested that they would prefer the stimulus spending promised by PiS than the continued fiscal frugality of PO. The campaign advertising of PiS has depicted a Poland plagued by poverty and corruption. Despite the enormous—indeed, unprecedented—gains made over the past decade, Poles still have incomes well below the European average, and large swaths of the country (particularly rural areas) are deeply impoverished. When these very real problems are combined with the lackluster and ideologically ambiguous governance of PO, the current survey results make sense.

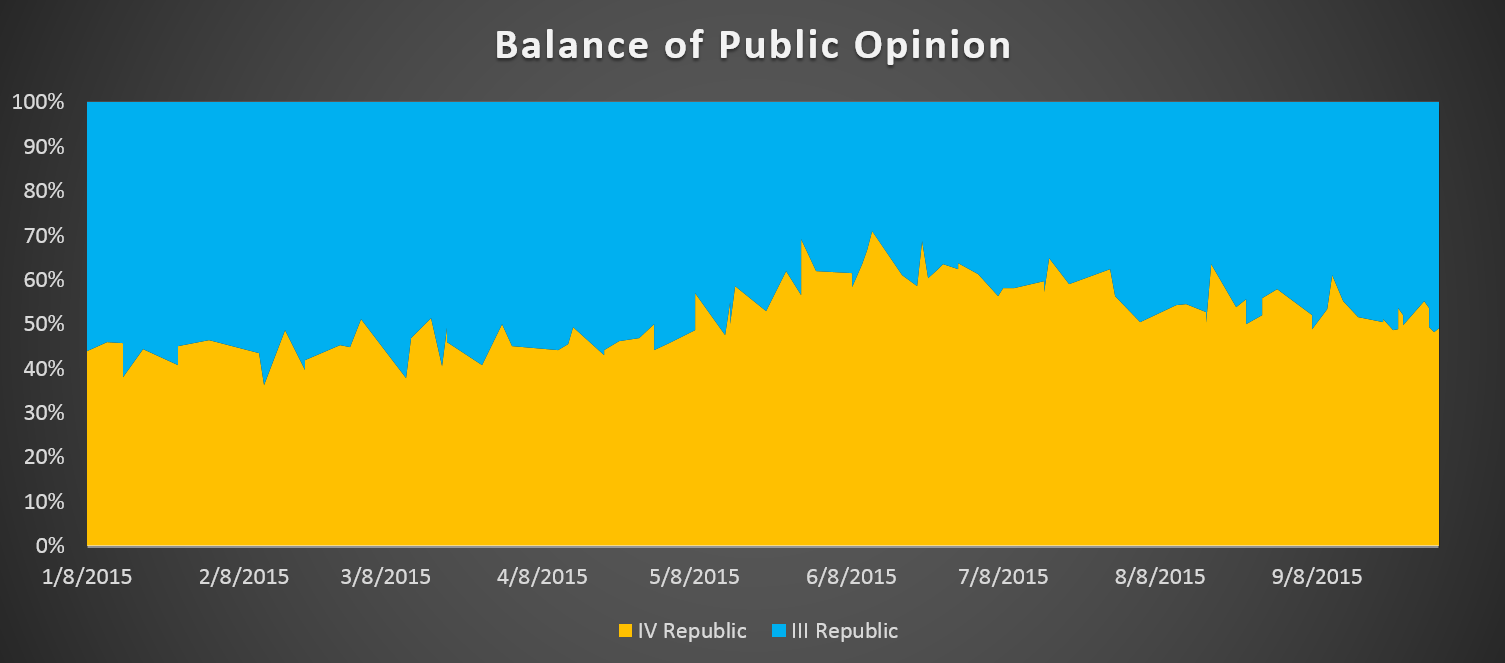

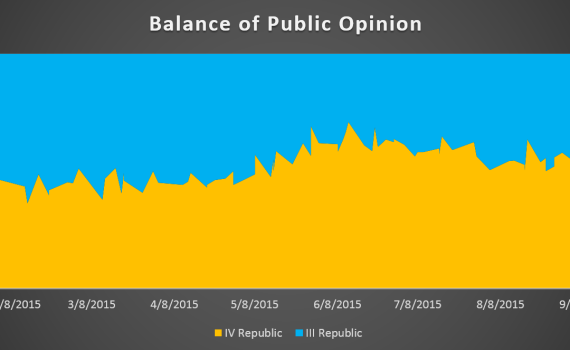

If we aggregate all the surveys from all the various firms so far this year, and group together the parties who support the current Polish state and those who want to replace it, we get a disturbing picture.

This is not to suggest that the particular vision of a systemic alternative proposed by Kaczyński and PiS enjoys broad support. He remains one of the most unpopular public figures in Poland today and his party is not even close to winning a majority of the overall vote. But frustration with PO combined with a belief that PiS won’t really make the transformations I’ve described above has led a great many Poles to consider casting a vote for PiS later this month. The prospect of a decisive PiS victory is lower today than it was in mid-summer, but it is still a very real possibility. A partial victory in which PiS would depend on coalition partners remains probable, but by no means foreordained. Stay tuned.