From Emigration to Immigration

There are countries that people try to escape from, and there are countries that these people try to escape to. In which category does Poland belong?

For well over a century Poland has been one of those countries that people wanted to leave, whether to escape political oppression, war, or poverty. Approximately two million Polish speakers settled in the United States in the decades leading up to the First World War, and that doesn’t even count the Jews who left territories that would later become part of independent Poland. By 1930 almost half a million Poles lived in the Chicago, and today 821,000 residents of that city identify as Polish-Americans. More recently, Poles have migrated in massive numbers to Great Britain and other EU countries, to the point where Polish is now the second most commonly spoken language in England (after English, of course).

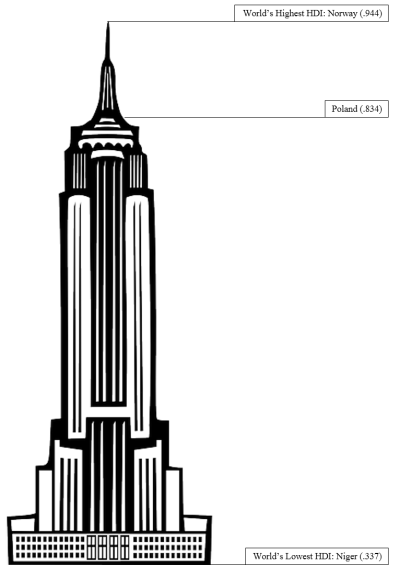

But times have changed, and Poland is rapidly transforming from a poor country that generates emigration into a relatively wealthy country that attracts immigration. Since 1989 the country’s GDP per capita has doubled, and in the midst of the world-wide recession after 2008 Poland was the only European country whose economy continued to grow. Comparing levels of prosperity in different countries is complicated and imprecise, but a good estimate is captured by the United Nation’s “Human Development Index” (HDI), which combines a range of statistics to create a rough measure of overall well-being. Using those figures, it is immediately clear that Poland is not a poor country; quite the contrary, the Poles are better off than 85% of the world’s population.

If the HDI were a skyscraper, the Poles would be living just below the penthouse suites.

This is not to say that there aren’t problems in Poland. With an average monthly income of 865 euros, Poles lags far behind Germans (2,995 euros) and they are even a bit behind the Czechs (970 euros). Around 17% of Poles live in poverty, a figure that has remained stubbornly consistent even as the overall economy has boomed. And although the residents of Warsaw now enjoy a standard of living similar to their peers in Berlin, some parts of the country rank among the poorest regions in the entire European Union.

Nonetheless, if we step back and look at Poland in a global context, it’s clear that the vast majority of people on Earth would have better lives in Poland than they currently do at home. So far that hasn’t translated into a massive wave of migration to Poland, but if current trends continue it is unavoidable that the Poles will have to contend with the same debates about immigration that their own emigration has sparked elsewhere in the past.

In recent days the first signs have appeared that this moment might arrive more quickly than anyone anticipated. Faced with a refugee crisis sparked mainly by violence in the Middle East, many in the EU support a broad distribution of these new arrivals across all member countries. The response from Hungary was particularly vehement: the far-right government of Viktor Orbán has been trying to close its borders and has used ugly rhetoric to justify its actions. Prime Minister Ewa Kopacz of Poland has been more restrained and has agreed to accept some refugees, but not nearly as many as the original EU plan proposed. Her government is trying to distinguish between an openness to housing refugees and an unwillingness to take in economic migrants, though in practice this distinction has been notoriously hard to sustain. Her reluctance might be due in part to the fact that she is in the midst of an uphill election battle, with a vote scheduled for October 25. Her center-right party currently trails the far-right opposition, which promises to prevent any foreigners from settling in Poland. Recent surveys show that more than a third of Poles would refuse to accept any refugees, with another third offering to welcome no more than 2,000 (in a country of 38 million). All this despite recent instructions from Pope Frances for every parish in Europe to prepare to house and feed refugees. Suddenly the famously Catholic Poles don’t seem so loyal to the Holy Father after all.

Some might be tempted to link the Polish reluctance to accept refugees to longstanding traditions of xenophobia and bigotry—indeed, some commentators have made just this connection. There is no doubt that a nationalist resistance to diversity is an important factor, but there is no reason to believe that the racism or islamophobia of the far right is a much bigger factor in Poland than it is in France, Austria, Switzerland, or anywhere else on the continent. When it comes to xenophobia, Poles are certainly no better than their European neighbors, but neither are they significantly worse.

What is different in Poland is the novelty of being in a position to give aid to others rather than receiving aid from others. Accepting their role as citizens of a successful first-world country (albeit among the poorer members of that club) is a big adjustment for Poles, and the older position of noble suffering and martyrdom is much more comfortable and familiar. Poles are understandably more inclined to stress the remaining gaps between their standard of living and that enjoyed by the Germans or the English, and less likely to recognize how far they have come over the past decade or so, or to see their own relative position vis-à-vis the rest of the world. I am not really criticizing this lack of perspective; in fact, I’d be surprised if it were otherwise. The right in Poland wants to remember their national history of victimization, and the left wants to focus everyone’s attention on the profound social inequities that continue to plague their country. But in the globalized context of the 21st century, Poland is now securely in the club of the privileged. The consequences of this unfamiliar condition can’t be avoided forever.