How Big is Poland?

Russia is bigger than Poland.

You’ve probably noticed that already, haven’t you?

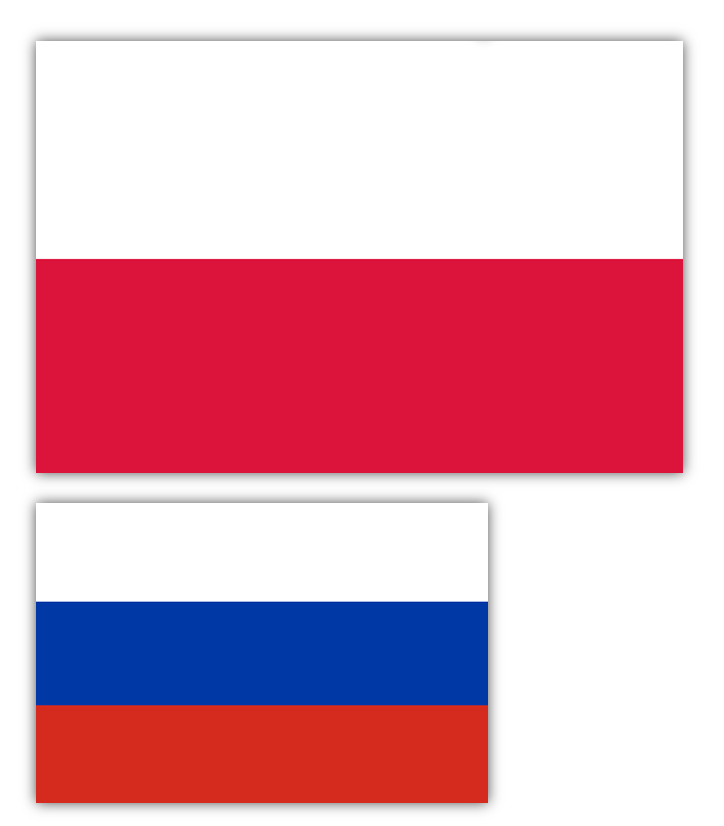

But the comparison between the two countries changes depending on what we are measuring. For example, if we measured population, the relationship would look like this:

Or if we used Gross Domestic Income, the proportions would change to this:

A measure of Total Household Consumption would turn the relationship upside down:

Now let’s bring this back home with a comparison of the number of American university students in 2013 who studied Russian, compared to the number studying Polish:

There’s something wrong with this picture. Unless someone wants to argue that we should measure the relative importance of various languages in terms of the land mass on which they are spoken, then Polish is way under-enrolled. I don’t doubt that more students should study Russian, given that country’s strategic importance and rich literary tradition. But at a time when our students and our administrators are so concerned with monetizing the academy, it seems to me that there are some serious market imperfections here. The household consumption figures are particularly striking, because they give us an indication of what would happen if we factored out Russia’s oil and natural gas wealth, which is almost entirely held by a tiny sliver of the country’s population. Russia’s Gini coefficient (a common measure of inequality) is near the top of the world’s rankings at 40.1, while Poland is just a bit higher than its West European neighbors at 34.1 (falling to 30.5 if we account for taxes and transfers—a figure on par with countries like Germany or Switzerland). That explains why Poland’s household consumption level is larger than Russia’s, despite the country’s smaller size. So for a business-minded student body, the appeal of Poland should be clear. We humanists are uncomfortable with this sort of reasoning, and I’ll be the first to admit that it seems somewhat vulgar to advocate language learning by making raw appeals to economic practicality. But we now live in a world in which we must fight for resources from university administrators and compete for enrollments among students, so we need every argument we can get. Poland’s economic position will probably improve even more over the coming decades, while Russia will face enormous problems because of its overreliance on extractive industries. If this prediction is correct, then we have a compelling reason to adjust the imbalances within the Slavic Departments at American universities.