Polish Optimism

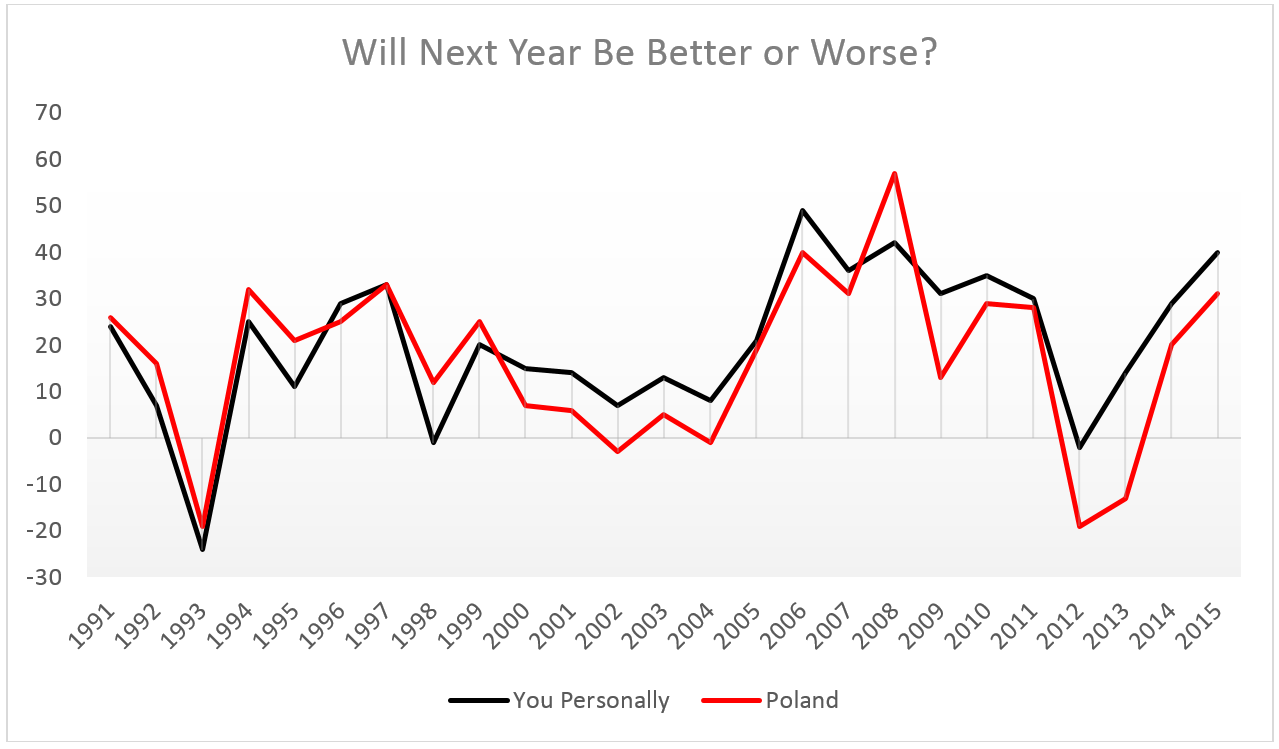

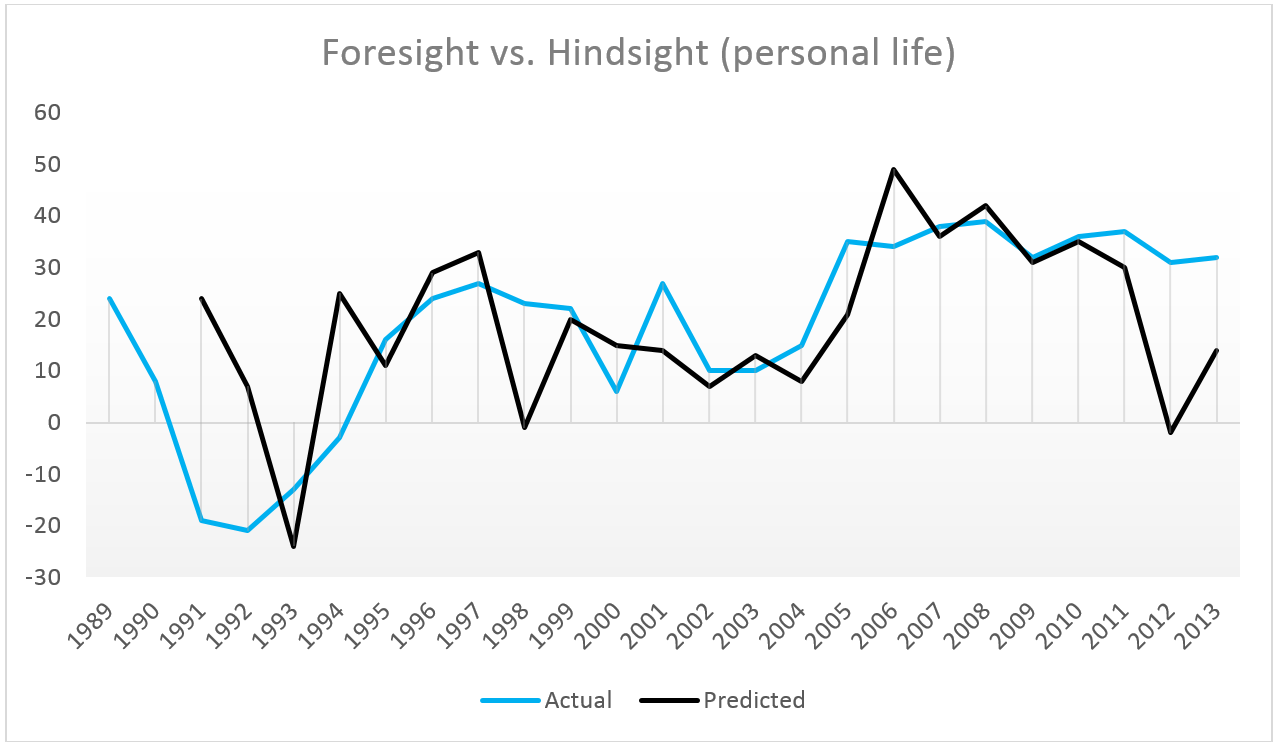

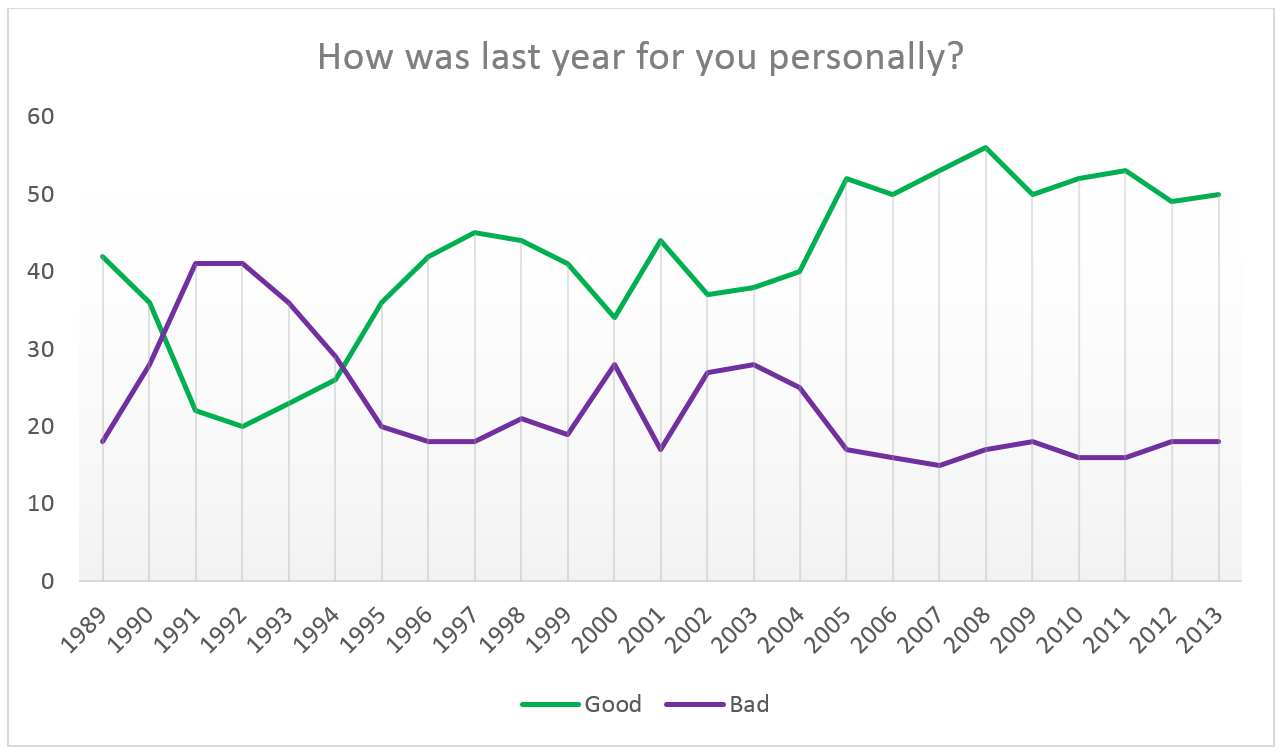

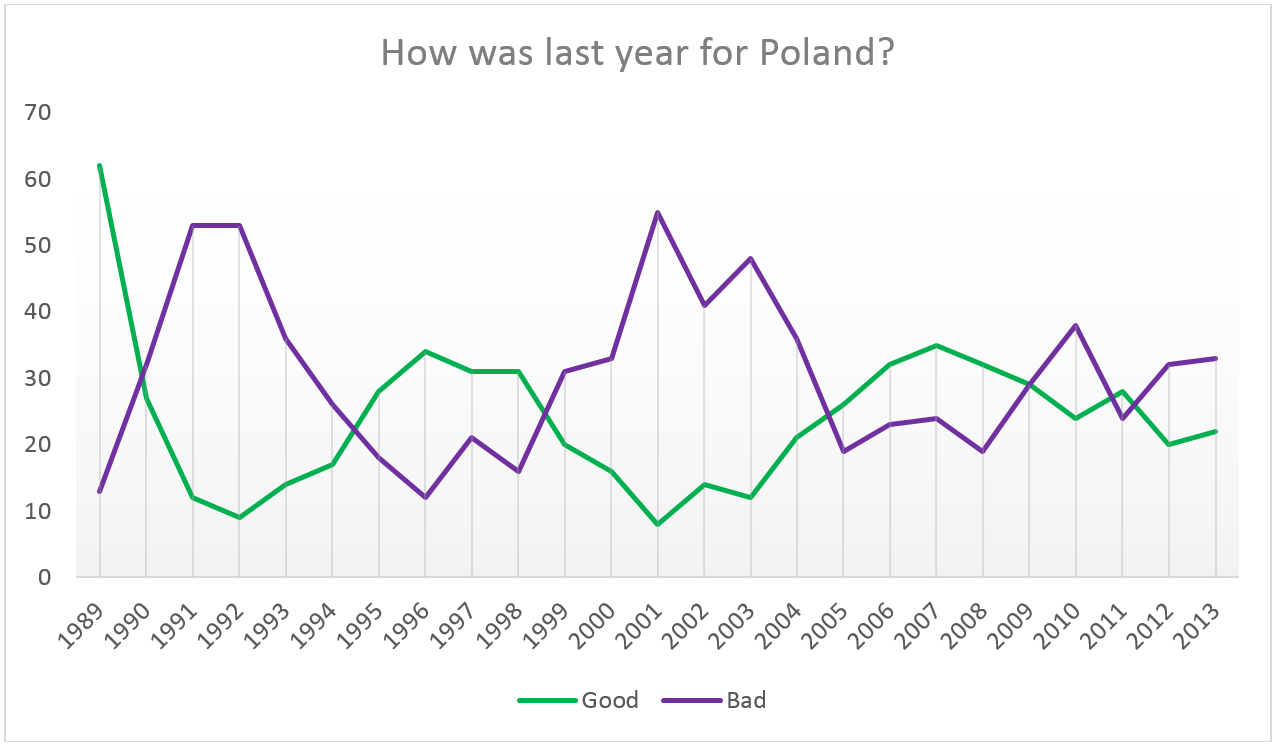

Every December since 1991, the Polish survey firm CBOS (Centrum Badania Opinii Społecznej) has been asking Poles whether they expected the coming year to be better or worse for themselves, their family, their workplace, their country, and the world. These results are fascinating to track, because they frequently reveal a curious gap between what people anticipate for themselves and for their country. In the charts below I have marked the difference between the number of people who predicting a better year to come and those expecting things to get worse. With only two brief exceptions, Poles have been more optimistic about their personal prospects than about Poland’s overall future. The most recent numbers show a sense of optimism on both accounts, but the gap remains. The anomalous spike in collective confidence in 2007 (predicting 2008) probably relates to the elections held in October of that year, a record-high turnout brought an end to the two-year government of the far-right party Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (PiS, or Law and Justice). As the world plunged into the Great Recession the following year, forecasts for the country’s future plummeted even as individual optimism remained reasonably high. In December of 2011 (another election year), when people were asked for their predictions for 2012, a sense of general gloom seemed to have set in. The contrasting reactions to the elections of 2007 and 2011 is quite noteworthy, particularly considering that the results were very similar, with the centrist, vaguely liberal party Platforma Obywatelska (PO, or Civic Platform) winning on both occasions. Given that all the macroeconomic indicators continued their gradual climb upward throughout these years, these changes in the level of optimism would seem to relate more to shifts in public rhetoric. The 2011 campaign was extraordinarily negative: PiS attempted to counteract the positive economic trends with a picture of impending doom, and PO tried to frighten the electorate with the prospect of a return to the chaotic years when PiS held power. We get a clearer view of what has been going on here by comparing the predictions people have made for each year with the assessment they offered once that year was over. Since 2005, despite all the political ebbs and flows, assessments of one’s personal fate during the previous year have remained relatively steady. At the moment, 56% of Poles consider 2014 to have been a good year, compared to only 12% who thought the year went badly (34% had no strong feelings either way). This range of assessments has held within a narrow band for the past decade. Meanwhile, predictions of future wellbeing spiked and collapsed, and remain gloomy today. Stepping back from the ups and downs, what strikes me most about these surveys is the degree of overall personal satisfaction they reflect, and the disconnect between measuring one’s own life and the life of the nation. Since 1994, more Poles have assessed their personal fortunes in a positive light than in a negative light—and rarely has the gap even been close. Evaluations of the nation’s fate, in contrast, jump up and down with little regard for what is happening in one’s personal life.