The Board is Set

After weeks of negotiations, it is finally clear what choices the Polish electorate will face during the elections this coming fall. There will be four significant blocs:

- Prawo i Sprawiedliwość (Law and Justice, or PiS): the radical-right nationalist party of Jarosław Kaczyński that has ruled the country since 2015

- Koalicja Obywatelska (Civic Coalition, or KO): led by Grzegorz Schetyna, this is basically the old Civic Platform party that has constituted the primary opposition to PiS for almost twenty years

- Koalicja Lewicy (Left Coalition, or KL): a union of left wing parties including the old Union of the Democrat Left (the former communist party from before 1989), and several new initiatives, most importantly a new group called Wiosna (Spring), the much anticipated but ultimately disappointing entry of the charismatic LGBT politician Robert Biedroń into national politics

- Polskie Stronnictwo Ludowe (Polish People’s Party, or PSL): the oldest party in Poland, with a constituency among small farmers. Strong in a few parts of the country based on deep clientelistic relationships

An article in today’s Gazeta Wyborcza by Włodzimierz Cimoszewicz captures a very common point of view with the headline: “The lack of a broad coalition is a victory for short-sighted foolishness.” In my opinion, nothing could be further from the truth. Yes, a field set out in this way virtually guarantees that PiS will emerge from the elections with more votes than any other grouping. In the trivial sense of the word, they will win the election. But to govern, getting more votes than others isn’t the goal: it’s positioning oneself to establish a majority by forming a coalition with other parties. With all that’s happened these past four years, it’s hard to see how PiS could form a coalition with anyone.

It is understandable that many people think of politics in terms of persuading “the people” to support this or that vision. This is the approach represented by PiS, which claims that its legitimacy stems from “the people” (which Kaczyński refers to as “the sovereign” [suweren]), a being who speaks with a single voice during elections. Based on this approach, whoever maneuvers into power after an election should then rule with unquestioned and unqualified authority until the next elections. Constitutional constraints, divisions of power between legislative and judicial branches, devolution of authority to local governments—all these things are irrelevant when faced with the power of “the sovereign’s” mandate. In a telling comment, a PiS politician, Jan Kilian, complained recently in a parliamentary speech that there was a disturbing pattern of “local governments carrying out their own policies without taking into account the policies of the central government.” This is the PiS worldview in a nutshell.

Ironically, it is also the implicit view of those across the political spectrum who argue that the voters need to be presented with a clear two-party alternative, PiS and Anti-PiS. Then “the sovereign” can speak with its singular voice, and the undeniable fact that PiS represents a minority of the electorate will cause them to lose their mandate to govern.

But what if there is no singular sovereign? What if the Poles are, in fact, a typical modern society with enormous differences between town and country, young and old, religious and secular, cosmopolitan and nationalist, rich and poor, etc., etc., etc. Yes, in a theoretical accounting it is obvious that “Anti-PiS” represents the majority of the population, but this includes quite a dizzying array of groups:

- businesspeople who are opposed to PiS’s fondness for state-owned firms

- libertarians who are opposed to PiS’s expansion of social welfare programs

- feminists who are opposed to PiS’s restrictions on reproductive choice

- secularists who are opposed to PiS’s clericalism

- cosmopolitans who are opposed to PiS’s hostility towards the EU

- intellectuals who are opposed to PiS’s heavy-handed and censorious cultural policies

- local politicians who are opposed to PiS’s centralization

- constitutional liberals who are opposed to PiS’s elimination of the independent judiciary

I could go on, but the point should be clear: any electoral campaign that is notionally “Anti-PiS” could not even mount a coherent negative political campaign, much less offer a coherent positive vision of how they would govern in a post-PiS world. This is what happened during the EU elections in May. A broad anti-PiS coalition did indeed take shape, but it was limited in its campaign to vague threats that Kaczyński would lead Poland out of the EU, and to abstract complaints about the constitutional violations of the past four years.

Getting a majority to agree that EU membership is a good thing and that the law should be obeyed is not hard. A Polexit referendum would never even come close to passing here, where the benefits of membership are simply too obvious. In fact, Poles are more pro-EU than people in any other EU country, and a survey in April showed support for membership hitting a record-high 91%.

But this misses the point. Let’s imagine a rural supporter of PSL who is a devout Catholic but also a believer in the rule-of-law and a supporter of EU membership. Now let’s imagine a young Varsovian who is strongly pro-choice, socialist, anticlerical, cosmopolitan, and a believer in the rule-of-law and a supporter of the EU. Finally, let’s imagine a business owner who is frustrated by PiS’s social spending and heavy-handed economic centralization—and is a believer in the rule-of-law and a supporter of the EU. If push came to shove, all three of these people might tell a survey-taker that they would vote for some notional anti-PiS. But can you even imagine an electoral campaign in which all three would be inspired to go to the trouble of voting in the first place? I know personally some of those urban leftists who would rather stay home or vote for a hopelessly small fringe-party rather than support a pro-business libertarian or pro-Catholic conservative. I also know some devout Catholics who despise PiS, but would never vote for a party that supports legalizing gay marriage.

The current political playing field may well hold just enough consolidation to ensure that all the major worldviews can find a home, without diluting the votes among parties that will fail to reach the 5% minimum needed for parliamentary representation. After all, PiS did not come to power in 2015 because it was so popular, but rather because the leftist parties failed to consolidate well enough to get any representation in parliament. It looks like that’s been resolved (knock on wood).

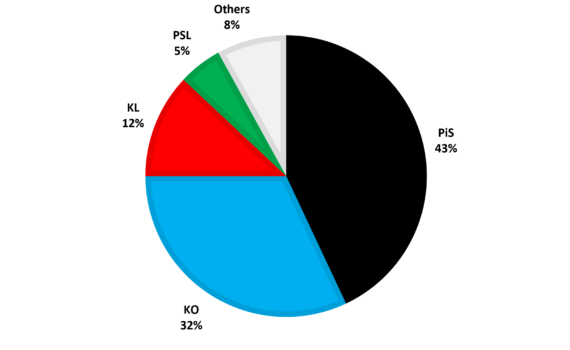

Given the four major groupings that appear to be entering the fight for 2019, and aggregating the survey data from several different sources from the past month, the elections should give us a picture approximately like this:

If we distribute these votes with the smaller parties eliminated, we get a sejm that looks like this:

In other words, no PiS majority, and virtually no path to a PiS government.

For the next few months, all eyes should be on the PSL. As of today, there is talk of them forming a coalition with a few other local organizations, which could be an incredibly risky move because of yet another quirk in Poland’s electoral law: coalitions require an 8% minimum rather than the usual 5% minimum. If PSL falls out of the picture, then the math would give PiS exactly half of the parliamentary seats.

One way or the other, it is going to be very close. The biggest danger now, as I see it, is that the opposition politicians are dispirited because they do not see a path towards any single group overtaking PiS’s support. No single party is going to replace PiS’s singular strength, and no coalition can possible cohere enough to challenge them. But that does not mean that the game is lost. The fact that some politicians and commentators are acting as if it was lost could become a self-fulfilling prophesy. Yet the actual balance of forces provides realistic ground for hope, and that’s what everyone should be focusing on now.