It’s Official

The official results of the local and regional elections in Poland are now in, and the biggest story is what did not happen. The Polish Electoral Commission has confirmed results in line with the independent exit polls, and so far there have been no reports of significant voter suppression,intimidation, or fraudulent tabulation.

Perhaps the top-line result was the turnout: 54.96% of the electorate voted last Sunday, an even larger figure than was initially forecast. That’s not only the largest turnout for local and regional elections in Poland’s history, but one of the largest for any election.

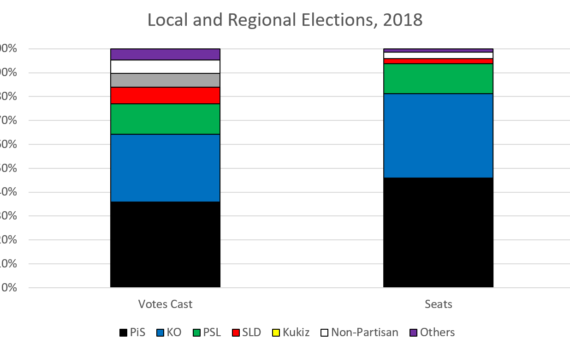

Once the votes were all counted and the complex arithmetic of Poland’s electoral laws were applied, the delegates to the country’s 16 regional assemblies (aggregated together) ended up as follows:

The differences between the votes cast and the actual seats gained reflects a longstanding feature of the Polish electoral system. Just as with elections to the national parliament, parties receiving less than 5% of the vote in any particular województwo receive no seats, and their votes are distributed proportionally among all the remaining parties. Because of this law, the far-right supporters of Paweł Kukiz have no representation at all, even though they got slightly more votes than the Non-Partisan movement (a group formed specially for these elections, bringing together local politicians unaffiliated with any national party). The latter group was concentrated in a few districts where they did quite well, whereas the former was scattered across the whole country. Still, the rough ideological distribution of the country is reflected here more accurately than during the 2015 parliamentary elections, when the disproportion between the votes cast and the parliamentary seats allotted was enormous.

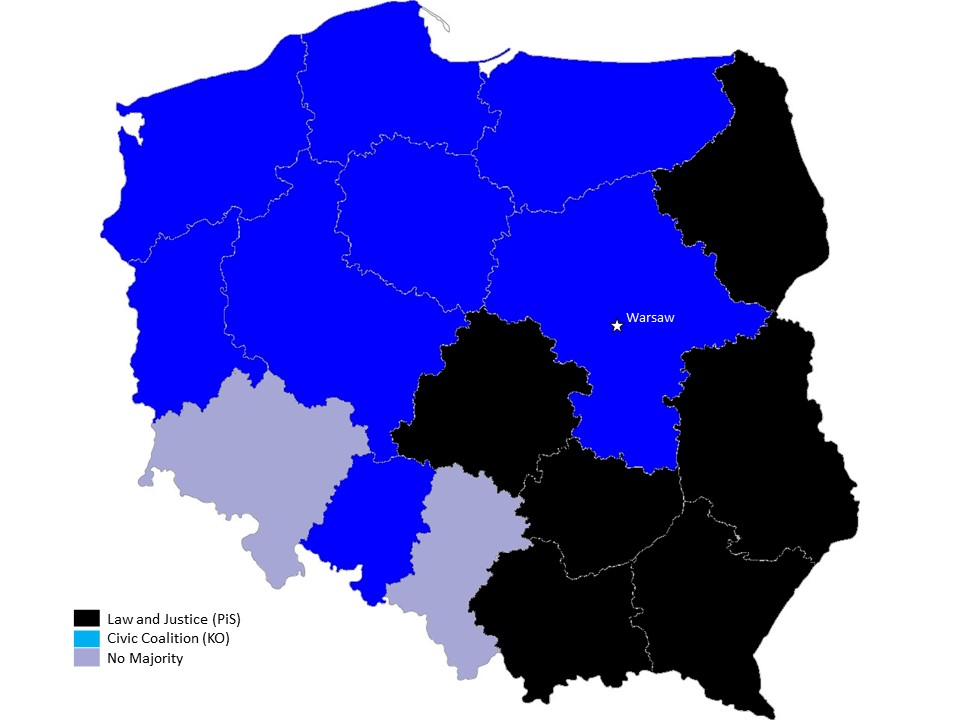

The most important feature of the distribution of seats (and votes) was that PiS is the largest single party, but that they fell short of a majority in most parts of the country. They did better than during he last round of regional elections (in 2014), but worse than they had hoped. Whereas previously they could establish control in only one województwo, today they have control of six. Two additional regions have no majority party, and coalitions will be needed to govern.

As originally predicted, the opposition won all the major cities, except for a couple that will have to a run-off between the top two candidates. In those, the opposition candidate is the overwhelming favorite. It would be a mistake, however, to conclude that Poland is divided into urban and rural worldviews. Instead, we have on one side PiS supporters who come mostly from rural areas and small town towns concentrated in the southeastern part of the country, and a diverse democratic opposition that encompasses both the remaining rural areas and every city of over 100,000 people.

If this is the best PiS can do after three years of heavy handed propaganda in the official state media, massive purges of every public institution, and an unabashed seizure of control over the judiciary, then they have a very serious problem. Many despaired in 2015 that “the Poles” had taken a turn away from democracy and shown themselves vulnerable to authoritarian, xenophobic, nationalist appeals. I never believed that, and today I’m even more confident that there has been little change in the long-term trends in Polish public opinion. PiS has never won more than a third of the popular vote, and they only took power because of quirks in the electoral law and because the left was so fragmented and disorganized in 2015.

The remaining question in my mind has always been: how far will Kaczyński go to retain power? He has been willing to use heavy-handed institutional pressure and patronage to gain loyalty over the structures of the Polish state. He has been willing to use the state media to spread programming as tendentious as anything seen in the communist era. He has threatened to “re-Polonize” the remaining private media outlets. He has defied the constraints of the Polish constitution and destroyed the independence of the judiciary. Against this backdrop, it seemed plausible that he would be equally willing to rig elections to ensure his victory. Nothing could truly stop him, given that the European Union has demonstrated that its enforcement mechanisms are toothless. So why didn’t he?

One possibility is that he doesn’t want to. Despite everything, perhaps he isn’t as authoritarian as so many of us have assumed. Maybe his talk about “illiberal democracy” is sincere insofar as he continues to believe that governments need to get an honest popular mandate. Maybe.

It seems more likely to me that he made a deliberate decision to allow these elections to go forward without interference because of two factors. First, the purge of the judiciary is not yet complete—in fact, Kaczyński decided to switch course last week and honor a European court ruling to temporarily re-hire some of the previously purged judges. I presume he did so because he didn’t want another clash with the EU to peak days before the elections. Without a reliable judiciary, it would still be difficult for PiS to get away with systematic voter suppression or manipulation, much less outright fraud. Second, Kaczyński probably believed that he didn’t need to shape the results of these elections. Most signs before the elections, until the very last week, pointed to a more decisive PiS victory. Even now, the ruling party is declaring victory because they did, after all, retain their status as the largest single political party in the country (even if this status ignores the fact that nearly every other political party is aligned against them, and would happily form an anti-PiS coalition). Since PiS can spin this as a victory, why bother with fraud? I don’t think this spin will work in the face of their dismal showing in Poland’s cities, but perhaps it’s good enough for the party base.

The final possibility is that something is happening behind the scenes within the PiS leadership, as various party factions fight for power. President Andrzej Duda, Justice Minister Zbigniew Ziobro, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki, Deputy Prime Minister Jarosław Gowin, Minister of the Interior Joachim Brudziński, and Defense Minister Mariusz Błaszczak have all made gestures suggesting that they are jockeying for a leadership role when Kaczyński someday retires. It could be that their efforts to demonstrate electoral backing for their various protégés and proxies created a need to run these elections cleanly.

No one can breath easily after these elections—not PiS, and not the opposition. Even the fact that the balloting appears to have been free and fair provides no assurances that the same will be true in 2019 during the high-stakes parliamentary elections. It’s quite possible that one result of these elections will be that PiS will strip the cities and województwa of their autonomy and funding so as to negate the power of the mayors and the regional assemblies. But one thing is clear: prior to last Sunday, it felt like PiS was an unstoppable machine, moving without any meaningful resistance to take over one sector of public life after another. Today the forces of democracy have reason—uncertain though it may be—to hope that a corner has been turned. One feature of authoritarian governments is that they tend to appear impregnable until the first cracks appear, after which they crumble like a house of cards. Could this be the first hairline fracture?