A New Generation

Cultural and social history are a bit like geology. Things change, but so slowly that it isn’t always obvious what happened until long afterwards. While political history operates on a much faster timeline, even here we often see events that churn the soil even while the bedrock moves at a glacial pace. Just consider the shift that happened between the elections of 2007 and 2015. The former is widely viewed as a humiliating repudiation of Jarosław Kaczyński’s Law and Justice Party (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, or PiS), while the latter marked their triumphant comeback with a self-proclaimed mandate to transform Poland. Analysts rushed to develop theories of why “the Poles” repudiated liberal democracy. Lost in the flurry of punditry was the fact that in 2007 PiS won 5,183,477 votes, and in 2015 they got 5,711,687 – out of a population of eligible voters of over thirty million people. Put differently, just under 2% of the electorate moved into PiS’s column. The consequences were enormous, but if we step back a few steps we realize that Polish society changed hardly at all.

With this in mind, what’s been happening in Poland over the past year has been stunning. It is as if a dam has broken, and the resulting wave has made Polish politics almost unrecognizable.

Starting from a bird’s eye view, support for PiS has fallen off a cliff. During the elections of October, 2019, PiS got 43.59% of the votes—not a majority, but in the fragmented political landscape of Poland, a relatively strong showing. Although the pre-election surveys had varied quite a bit (mostly because of different methodologies), the average of all the polls during the month before that election had predicted roughly this result. At the start of the COVID pandemic in March, 2020, PiS had lost some support, but a “rally around the flag during a crisis” sentiment pulled them back up to 44%. It’s been all downhill from there. The average of all polls currently has PiS at 31.6%, with a range from 26% (using live telephone interviews) to one extreme outlier at 40% (using an automated internet survey). Jarosław Kaczyński is currently the most unpopular politician in the country, with a favorability rating of 17% and an unfavorability rating at a jaw-dropping 74%. Other right-wing politicians aren’t far behind: President Andrzej Duda’s is disliked by 64% of Poles, Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki by 62%, and Justice Minister Zbigniew Ziobro (ironically, Kaczyński’s leading rival for leadership of the far right) by 71%.

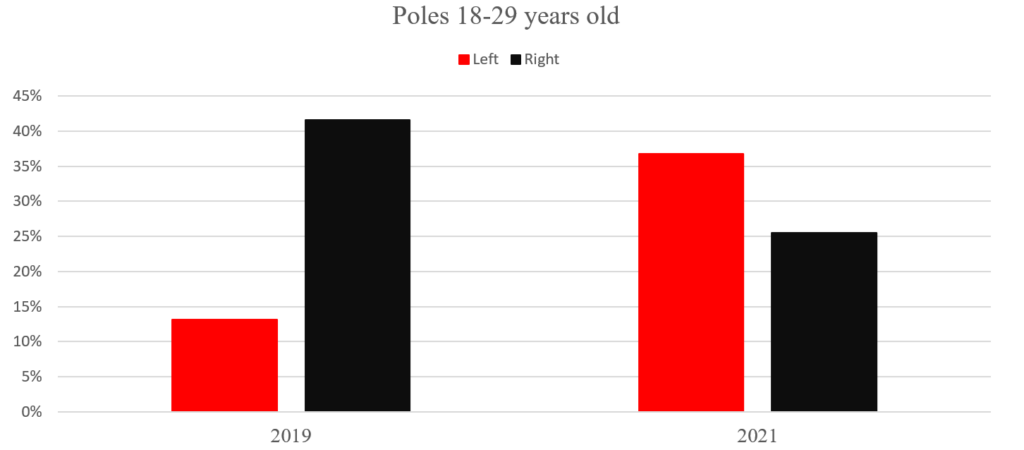

As dramatic as those numbers are, there is an even greater tectonic shift just underneath them. Put simply, young people have abandoned PiS almost entirely. In 2019 the supporters of PiS already skewed somewhat towards more elderly voters, with 55% of their voters age 50 or above. Today, 76% of the party’s support comes from us oldsters. Among those under age 30, the current government has the trust of a whopping 9%. 34% of that cohort consider themselves to be somewhat leftist or very leftist, compared to 28% who affiliate with the right. That last figure needs to be put into perspective to see what has happened. A different survey compared 18-29 year-olds in Poland between 2019 and 2021, and found that their affiliation flipped from right to left over the course of those two years.

Not surprisingly, nearly all of this change has come among women. Whereas in 2019 a plurality of both women and men under 30 identified with the right, by 2021 a plurality of women supported the left, while a (slightly smaller) plurality of men supported the right. Among young men, right-wing views remain twice as popular as left-wing views, but women have swung in a completely different direction.

I’m sure that the PiS government’s bad management of the COVID crisis has contributed to the overall fall in support, but that’s not the biggest issue here. The erosion of constitutional rule and the separation of powers has continued apace since PiS’s re-election in 2019, but the sort of people upset by those matters were already aligned with the opposition. The big change came when the subordination of the judiciary was brought home to everyone—above all, Polish women—in the most intimate way possible, when the constitutional tribunal banned nearly all abortions last fall. The mass protest movement that exploded in response—which took the name of the “Women’s Strike”—has dwarfed every previous expression of opposition to Law and Justice rule. The government has responded with (still relatively contained) demonstrations of force, but this has only made the Women’s Strike stronger.

I’ve heard some grumbling among those who have opposed PiS from the start—people of my generation who are nowadays labeled dziadersi (a slang similar to “boomer” in English, but with an angrier edge to it). “Where were all these protesters in 2016 and 2017,” my friends say, “when we warned that undermining the rule of law and the constitutional protections of our civil rights would lead us to precisely this sort of catastrophe?” It’s true that the stage for the abortion ban was set when PiS subordinated the judiciary to political control, but let’s be more understanding. It required a relatively high level of political engagement to be directly touched by what Kaczyński was doing during those early years; meanwhile, nearly everyone at the time noticed the 500 złoty monthly payments that PiS introduced for struggling families. And the anti-PiS opposition was led by…well, dziadersi, and far too many of us were still fighting the political battles of the 1990s and early 2000s. The abortion ban is, in a way, a civics lesson for all of us. For some, it shows that when judicial independence is eliminated, the results will sooner or later hit everyone. For others, it serves as a reminder that polite 20th century liberalism doesn’t have much to offer in the precarious world of 2021.

It’s a very open question what will happen now, but one thing is beyond doubt: Polish political culture has been utterly transformed. It is time for the generation of 2020 to set the agenda, and the world they eventually create will not have much space for the ideas and ideals that PiS tried to impose upon Poland. Kaczyński might hold on to power for a few more years. It’s even possible that he will resort to even more authoritarian measures, so that things will get worse before they get better. But his primary goal has always been more than just holding power: he wanted to shape the worldview of the next generation of Poles.

Ironically, he did. Just not in the way he wanted.