How to Remember 1989

The following essay was just published by The Global Post

Thirty years ago, on June 4, 1989, there were free elections in Poland – the first multiparty elections since WWII, and the beginning of a cascade of events that culminated in the collapse of all the communist regimes of Eastern Europe. Two years later, the USSR itself would cease to exist, and the Cold War would come to an end. There was doubtlessly an excess of liberal triumphalism in 1989, but it can’t be denied that it was a year of genuine triumph for the forces of democracy, pluralism, and openness. And it all started in Poland.

Sadly, it seems that what goes around, comes around. Three decades after those thrilling events, we are witnessing the re-consolidation of dictatorial regimes in Poland, Hungary, and Russia, while similar anti-liberal forces rise throughout the region. The rhetoric is a bit different nowadays, with the slogans coming from the nationalist right rather than the communist left, but the methods of authoritarianism are frighteningly similar. The Polish, Hungarian, and Russian courts, media, cultural institutions, and educational systems are all under the control of each country’s ruling party, which uses this power to reshape society and stamp out liberal values of tolerance, diversity, pluralism, and respect for legal norms. When we recall that the communists of the 1970s and 1980s had themselves become increasingly xenophobic and nationalistic, even the rhetorical differences fade. Perhaps, in retrospect, the changes of 1989 weren’t as dramatic as they seemed at the time. Should we even be celebrating this year’s anniversaries?

Yes, we should – but with an eye towards the unfulfilled promise of that amazing moment thirty years ago. As we celebrate, we ought to return to the actual hopes and goals of those who brought about the fall of communism, and push aside once and for all the radical austerity ideology that was imposed upon Eastern Europe afterwards.

When the activists of the Solidarity labor movement began negotiating with the communist authorities in early 1989, they had both political and economic demands. Those political goals were achieved beyond their wildest dreams: one of their own leaders would be Prime Minister by the end of the summer, and within a few years Poland had an independent judiciary, a wide-open media landscape, and a multi-party democracy. Solidarity’s economic goals, however, were immediately and ruthlessly discarded. Revisiting those demands today is like peering into an alternative universe, one in which it seemed plausible to demand that that wages be indexed to inflation, that full employment be guaranteed by the state, and that independent unions play a large role in managing firms. Though the label wasn’t used at the time, it was a formula for democratic socialism, not neoliberal capitalism. This is what was promised in the deal that emerged from the “Round Table Talks.”

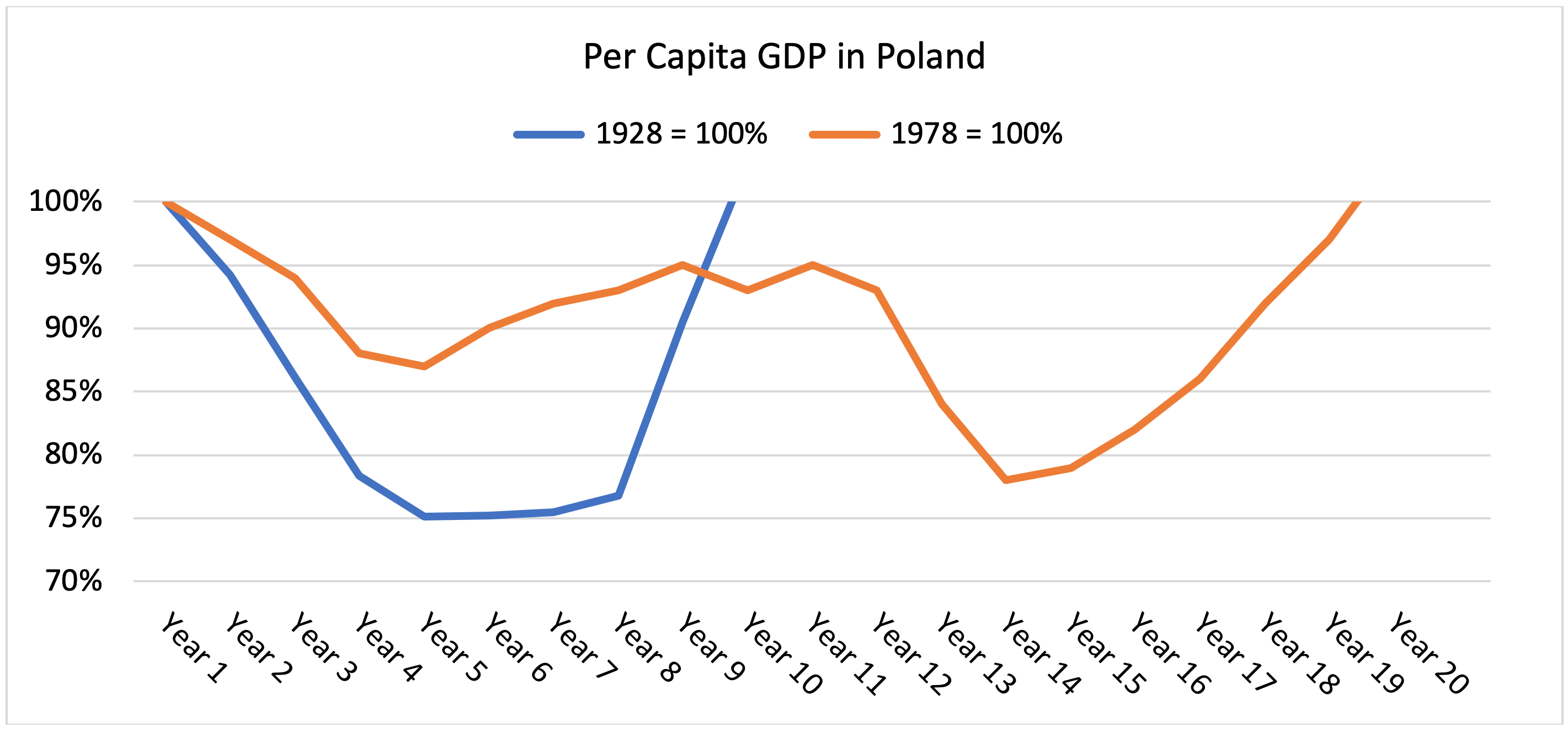

That promise was never kept. As the new post-communist government embraced a series of radical austerity measures known as “shock therapy,” Poland plunged into one of the deepest recessions every recorded. In fact, if we combine the crisis of the late-communist era with the post-communist recession, and compare that to the Great Depression of the 1930s, we see a shocking result:

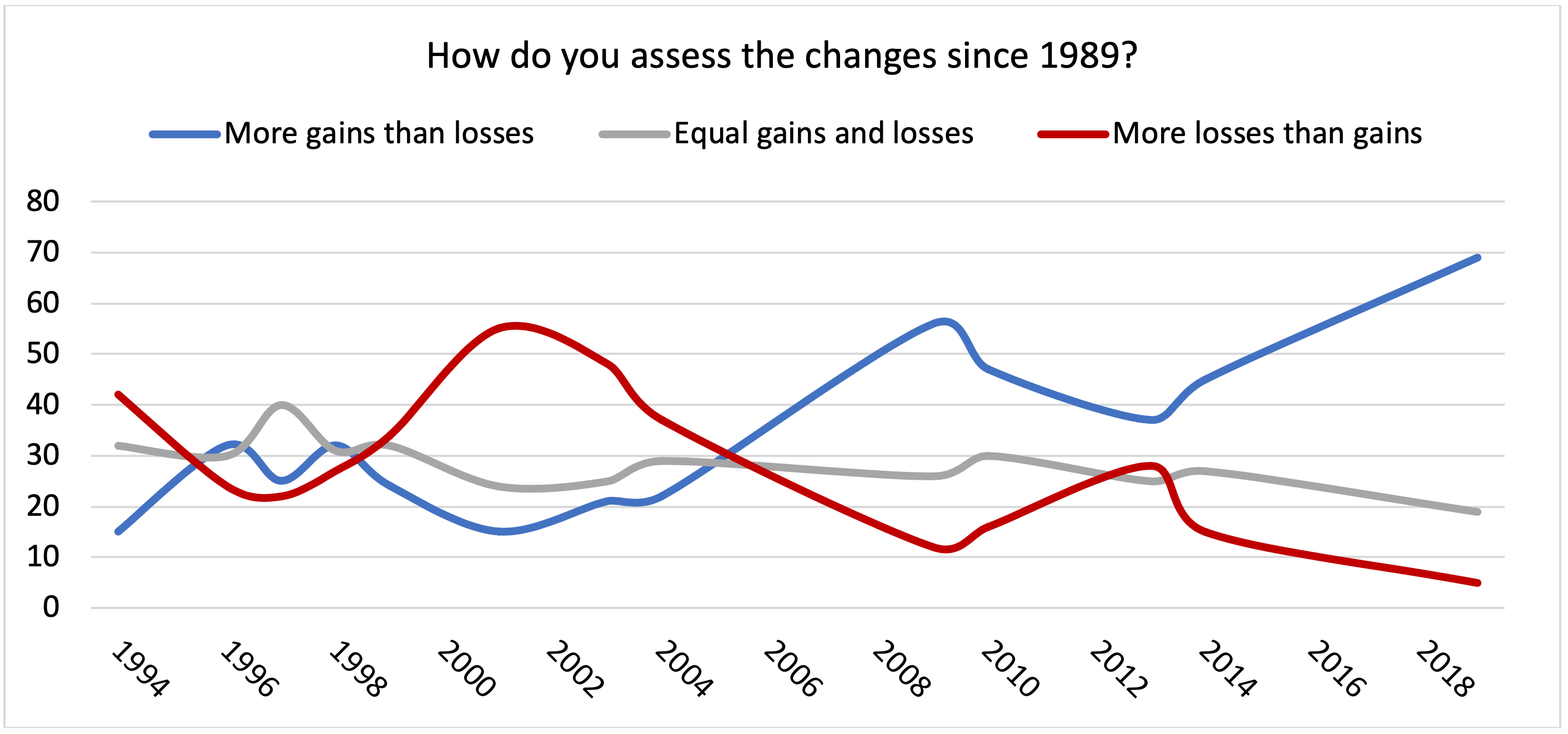

That second plunge in the late 20th century recession, which came right after 1989, helps explain why so many Poles almost immediately felt an intense buyer’s remorse about abandoning the communist system. The CBOS survey firm has been asking Poles how they felt about the post-communist transformations, and until recently opinions have been divided, and subject to a lot of fluctuation:

In part, the much-delayed consensus that the overthrow the Polish People’s Republic was worthwhile comes from the fact that the country’s overall economic success has become undeniable. In the aggregate, Poles now are richer than they have ever been before—by a lot.

But note that drop in 1978 and the even deeper drop after 1989. Those who experienced the events of those years would be forgiven for wondering why so many outsiders were celebrating the fall of communism. Moreover, even as incomes eventually recovered and then rose to new heights, it came at the expense of significantly longer working hours, incomparably more stress, frayed family relations and social bonds, and massive cultural change. For all these reasons, those old enough to remember the Polish People’s Republic remain ambivalent even today about the transformations. The growing consensus that 1989 was worthwhile comes primarily from those who came of age after the 1990s, whose “memory” of communism comes from schoolbooks, novels, films, and TV shows that consistently depict the old system in uniformly dark colors.

21st century politics in Poland—and throughout Eastern Europe—has been dominated by a battle between neoliberals (who want to defend both the economic and political system established after 1989) and nationalists (who emphasize the darker sides of the new order, but blame it on a vast conspiracy of foreigners and hidden ex-communists). Now the latter are in power, and they are dismantling all the gains of the former—political and economic alike. The authoritarian regime of Jarosław Kaczyński’s “Law and Justice” party is distinctly awful, and I wouldn’t want to imply a symmetry between them and their liberal opponents. Nonetheless, today’s tragic erosion of constitutional norms is at least in part a consequence of the failures of the 1990s and early 2000s. Missing from the political scene back then was an agenda that would implement all the aspects of the Round Table Accords: an agenda that combined liberal democratic freedoms in the political and cultural realm with democratic socialism in the economic realm.

This year, as we celebrate the anniversary of 1989, let’s remember that path not taken. It’s too late to recover it now, because the living memory of the communist era has been replaced by the politics of memory, and that’s been thoroughly poisoned by the competing distortions of both liberal anticommunism and nationalist anticommunism. No one shouldwant to recover communism—there is, despite everything, something to celebrate with this year’s anniversaries. The sigh of regret that accompanies those commemorations is for the vanished and vanquished agenda of the 1980s: the program that didn’t want to throw the egalitarian baby out with the communist bathwater.