The Ghost of Referendum Past

What if you held a referendum and no one came?

That’s what happened in Poland last weekend. The story is almost comically bizarre, but it exemplifies some very serious problems with the current political atmosphere in Poland.

During last May’s presidential elections a rock musician with no political experience named Paweł Kukiz stunned everyone by getting 21% in the first round of voting. His supporters were an ideological mishmash, united only by a disgust of the political establishment and a somewhat nihilistic desire to pull down the current system. But the only clear and consistent policy recommendation Kukiz made was oddly wonkish: a shift from proportional representation to single-mandate voting districts. Then-incumbent President Bronsiław Komorowski, in a transparent but misguided attempt to win over Kukiz’ electorate before the second round of voting, announced a referendum on this issue. He also tagged on a couple other seemingly popular proposals: a reform in the system of public campaign financing and a taxpayer-friendly revision of how disputes with the state revenue collection system get resolved. Since very few people ever truly cared about any of these questions, that ploy failed to boost Komorowski’s support and he lost the election to his far-right opponent, Andrzej Duda. But the referendum was already scheduled, so last Sunday it went ahead as planned. The results are irrelevant, because a mere 7.8% of the electorate turned out to vote (no, that it not a typo). Since 51% of eligible voters must show up for a referendum to be binding, the proposals failed.

Meanwhile, the newly inaugurated President Duda decided to draw upon the same tactic, announcing a referendum of his own. His issues echoed some of the policy proposals of his party’s election campaign: lowering the retirement age, blocking the privatization of some state forests, and raising the age at which children start elementary school. All three issues would have reversed reforms instituted by the current government, which President Duda hopes to topple in parliamentary elections this coming October. Unfortunately for him, to schedule his referendum he needed the consent of the Polish senate, which was not forthcoming.

To even summarize the policy implications raised by these two referenda would take us deep into the weeds of irrelevance. An outsider might be surprised that the heavy club of a referendum would be used for such matters, which might seem more appropriate for regular parliamentary procedures. In fact, an insider would be equally surprised, because the Polish constitution only allows for referenda on matters of fundamental national concern. The whole episode seemed to trivialize the political process, a fact recognized by the 92.2% of the voters who opted to enjoy a late-summer Sunday and ignore the whole show.

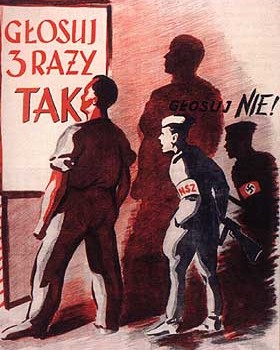

But historians (and even ordinary Poles with long enough memories) could not help but notice a disturbing parallel from the country’s past. In 1947 the communists used a virtually identical tactic in their successful maneuvering for power. They selected three issues that seemed to enjoy widespread popularity—all three of which had already been passed into law—and put them before the public in a referendum. The point was to get people to vote for issues backed by the communists, giving the party some much needed public legitimacy. It was pure political theater, but it was also a key moment in a brutal struggle for absolute power.

The fact that Poland’s leading party’s—both of them—are employing such tactics today might be a coincidence. And it would be hyperbolic to suggest that the stakes now are even remotely similar to those in 1947. On the other hand, few political contests nowadays would meet that high standard, so failing to do so should not diminish the battle of fundamental importance that is currently underway. On the one side is Law and Justice (Prawo i Sprawiedliwość, or PiS), a radical-right populist movement which promises to reconstruct the state along the anti-liberal, nationalist lines followed by Viktor Orbán in Hungary. On the other side is Civic Platform, which is not really a political party at all, but a broad coalition of forces stretching from the center-left to the center-right whose only shared interest is keeping PiS from power. For the past decade this amorphous formation has successfully governed Poland by focusing on technocratic issues and a vague Euro-liberalism. That approach clearly isn’t working any more, as demonstrated by Duda’s victory in the presidential elections. Current political surveys suggest that PiS is likely to win in the October parliamentary elections as well.

Make no mistake: the stakes are huge. After the fiasco of the Greek crises this summer and the current refugee emergency, the European Union can ill afford another major blow. If a radical protest movement like PiS gains power in Poland it would be (correctly) interpreted as a profound repudiation of the consensus norms of the EU elites. Smaller countries like Hungary or Greece can be quarantined to some (limited) extent, but a similar turn in a country as large as Poland would be much more serious. So if we see the Poles employing political methods that evoke the frightening years of struggle in the late 1940s, we shouldn’t be surprised. Over 90% of the electorate chose to turn their backs on the theatrics of last Sunday’s referendum, and I can hardly blame them. But they need to turn around now and start paying close attention to the very real struggle for power that is underway.